QURNA, Egypt — It is one of the 20th century’s most iconic photos: British

archaeologist Howard Carter inspecting the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun in 1922

as an Egyptian member of his team crouches nearby shrouded in shadow.

اضافة اعلان

It is also an apt

metaphor for two centuries of

Egyptology, flush with tales of brilliant foreign

explorers uncovering the secrets of the Pharaohs, with Egyptians relegated to

the background.

“Egyptians have

been written out of the historical narrative,” leading archaeologist Monica

Hanna told AFP.

With the recent

100th anniversary of Carter’s earth-shattering discovery in November 1922 — and

the 200th this year of the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, which unlocked the

ancient hieroglyphs — Egypt is demanding that its contributions be recognized.

British archaeologist Howard Carter examines the sarcophagus containing the body of Tutankhamun.

British archaeologist Howard Carter examines the sarcophagus containing the body of Tutankhamun.

Egyptians “did all

the work” but “were forgotten”, said chief excavator Abdel Hamid Daramalli, who

was born “on top” of the tombs at Qurna near Luxor that he is now in charge of

digging.

Even Egyptology’s

colonial-era birth — set neatly at Frenchman Jean-François Champollion cracking

the Rosetta Stone’s code in 1822 — “whitewashes history”, according to

specialist researcher Heba Abdel Gawad, “as if there were no attempts to

understand

Ancient Egypt until the Europeans came”.

The “unnamed

Egyptian” in the famous picture of Carter is “perhaps Hussein Abu Awad or

Hussein Ahmed Said”, according to art historian Christina Riggs, a Middle East

specialist at Britain’s Durham University.

The two men were

the pillars, alongside Ahmed Gerigar and Gad Hassan, of Carter’s digging team

for nine seasons. But unlike foreign team members, experts cannot put names to

the faces in the photos.

‘Unnoticed and unnamed’

“Egyptians remain unnoticed, unnamed, and virtually unseen in their

history,” Riggs insisted, arguing that Egyptology’s “structural inequities” reverberate

to this day.

But one Egyptian

name did gain fame as the tomb’s supposed accidental discoverer: Hussein Abdel

Rasoul.

Despite not

appearing in Carter’s diaries and journals, the tale of the water boy is

presented as “historical fact”, said Riggs.

On November 4,

1922, a 12-year-old — commonly believed to be Hussein — found the top step down

to the tomb, supposedly because he either tripped, his donkey stumbled, or

because his water jug washed away the sand.

The next day,

Carter’s team exposed the whole staircase and on November 26, he peered into a

room filled with golden treasures through a small breach in the tomb door.

According to an

oft-repeated story, a half century earlier two of Hussein’s ancestors, brothers

Ahmed and Mohamed Abdel Rasoul, found the Deir Al-Bahari cache of more than 50

mummies, including Ramesses the Great, when their goat fell down a crevasse.

But Hussein’s

great-nephew Sayed Abdel Rasoul laughed at the idea that a goat or boy with a

water jug were behind the breakthroughs.

Riggs echoed his

skepticism, arguing that on the rare occasions that Egyptology credits

Egyptians with great discoveries, they are disproportionately either children,

tomb robbers, or “quadrupeds”.

The problem is that

others “kept a record, we didn’t”, Abdel Rasoul told AFP.

‘They were wronged’

Local farmers who knew the contours of the land could “tell from the

layers of sediment whether there was something there”, said Egyptologist Abdel

Gawad, adding that “archaeology is mostly about geography”.

Profound knowledge

and skill at excavating had been passed down for generations in Qurna — where

the Abdel Rasouls remain — and at Qift, a small town north of Luxor where

English archaeologist William Flinders Petrie first trained locals in the

1880s.

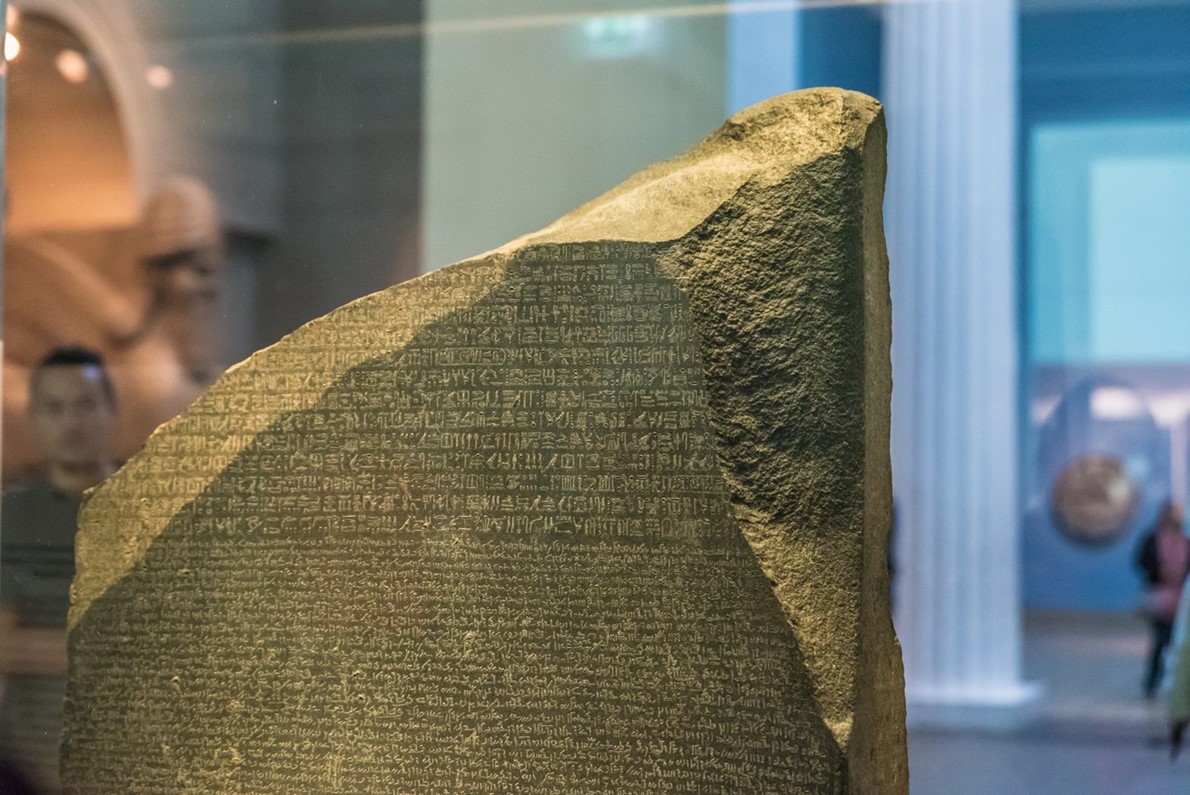

The Rosetta Stone on display at the British Museum in London, United Kingdom.

The Rosetta Stone on display at the British Museum in London, United Kingdom.

Mostafa Abdo Sadek,

a chief excavator of the Saqqara tombs near

Giza, whose discoveries have been

celebrated in the Netflix documentary series “Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb”, is

a descendant of those diggers at Qift.

His family moved

600km north at the turn of the 20th century to excavate the vast necropolis

south of the Giza pyramids.

But his

grandfathers and great-uncles “were wronged”, he declared, holding up their

photos.

Their contributions

to a century of discoveries at Saqqara have gone largely undocumented.

‘Children of Tutankhamun’

Barred for decades from even studying Egyptology while the French

controlled the country’s antiquities service, Egyptians “were always serving

foreigners”, archaeologist and former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass told

AFP.

Another

Egyptologist, Fatma Keshk, said we have to remember “the historical and social

context of the time, with Egypt under British occupation.”

The struggle over

the country’s cultural heritage became increasingly political in the early 20th

century as Egyptians demanded their freedom.

“We are the

children of Tutankhamun,” the diva Mounira al-Mahdiyya sang in 1922, the year

the boy pharaoh’s intact tomb was found. The same year Britain was forced to

grant Egypt independence, and the hated partage system that gave foreign

missions half the finds in exchange for funding excavations was ended.

But just as

Egyptians’ “sense of ownership” of their heritage grew, ancient Egypt was

appropriated as “world civilization” with little to do with the modern country,

argued Abdel Gawad. “Unfortunately that world seems to be the West. It’s their

civilization, not ours.”

While the contents

of Tutankhamun’s tomb stayed in Cairo, Egypt lost Carter’s archives, which were

considered his private property.

The records, key to

academic research, were donated by his niece to the Griffith Institute for

Egyptology at

Britain’s Oxford University.

“They were still

colonizing us. They left the objects, but they took our ability to produce

research,” Hanna added.

This year, the

institute and Oxford’s Bodleian Library are staging an exhibition,

“Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive”, which they say sheds light on the “often

overlooked Egyptian members of the archaeological team.”

Excavators’ village razed

In Qurna, 73-year-old Ahmed Abdel Rady still remembers finding a mummy’s

head in a cavern of his family’s mud-brick house that was built into a tomb.

The abandoned village of Qurna in Luxor, Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

The abandoned village of Qurna in Luxor, Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

His mother stored

her onions and garlic in a red granite sarcophagus, but she burst into tears at

the sight of the head, berating him that “this was a queen” who deserved

respect.

For centuries, the

people of Qurna lived among and excavated the ancient necropolis of Thebes, one

of the pharaohs’ former capitals that dates back to 3100 BC. Today, Abdel

Rady’s village is no more than rubble between the tombs and temples, the twin

Colossi of Memnon — built nearly 3,400 years ago — standing vigil over the

living and the dead.

Four Qurnawis were

shot dead in 1998 trying to stop the authorities from bulldozing their homes in

a relocation scheme. Some 10,000 people were eventually moved when almost an

entire hillside of mud-brick homes was demolished despite protests from

UNESCO.

In the now deserted

moonscape, Ragab Tolba, 55, one of the last remaining residents, told AFP how

his relatives and neighbors were moved to “inadequate” homes “in the desert”.

The Qurnawis’

dogged resistance was fired by their deep connection to the place and their

ancestors, said the Qurna-born excavator Daramalli.

But the

controversial celebrity archaeologist Hawass, then head of Egypt’s Supreme

Council of Antiquities, said “it had to be done” to preserve the tombs.

Egyptologist Hanna,

however, said the authorities were bent on turning Luxor into a sanitized

“open-air museum... a Disneyfication of heritage”, and used old tropes about

the Qurnawis being tomb raiders against them.

Sayed Abdel

Rasoul’s nephew, Ahmed, hit back at what he called a double standard. “The

French and the English were all stealing,” he told AFP. “Who told the people of

Qurna they could make money off of artefacts in the first place?”

‘Spoils of war’

Over the centuries, countless antiquities made their way out of Egypt.

The Colossi of Memnon near Luxor, Egypt.

The Colossi of Memnon near Luxor, Egypt.

Some, like the

Luxor Obelisk in Paris and the Temple of Debod in Madrid, were gifts from the

Egyptian government. Others were lost to European museums through the

colonial-era partage system.

But hundreds of

thousands more were smuggled out of the country into “private collections all

over the world”, according to Abdel Gawad.

Former antiquities

minister Hawass is now spearheading a crusade to repatriate the Rosetta Stone

and the Dendera Zodiac, and his petition has already attracted more than 78,000

signatures.

Returning the two

artefacts to Egypt would show “the commitment of Western museums to

decolonizing their collections and making reparations for the past,” the

petition says.

The Rosetta Stone

has been housed in the British Museum since 1802, “handed over to the British

as a diplomatic gift”, the museum told AFP.

But for Abdel

Gawad, “it’s a spoil of war”.

The Frenchman

Sebastien Louis Saulnier meanwhile had the Dendera Zodiac blasted out of the

Hathor Temple in Qena in 1820. The celestial map has hung from a ceiling in the

Louvre in Paris since 1922, with a plaster cast left in its place in the

southern Egyptian temple.

“That’s a crime the

French committed in Egypt,” Hanna said, behavior no longer “compatible with

21st-century ethics.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News