AMMAN — Questions came to the mind of 19-year-old Ayham

when the cashier at the

Traffic Department in Amman asked him to pay JD154 for

a Jordanian driver’s license.

اضافة اعلان

He only had JD38,

since this was the fee his friend paid recently when he applied for his driving

license.

“How is my friend

different from me?” asked Ayham. “He and I were born the same year in Amman,

and we speak the same dialect. We sang the national anthem and saluted the flag

together at the same school.”

Ayham sighed as

he asked the cashier for the required amount again. His response was, “Sorry

but you are not Jordanian”.

Ayham replied “I

am the son of a Jordanian woman,” to which the cashier at the window responded

“they are not (considered) Jordanian citizens.”

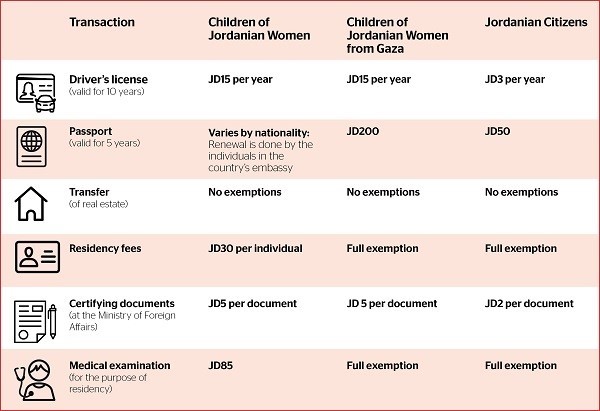

Jordanian women’s

children who reside in the kingdom pay higher fees than citizens when they

request or certify official documents, or when they renew their driver’s

licenses.

Ayham’s case is

similar to 21-year-old Mohammad, who travelled abroad to complete his

education. Once back, he approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and

Expatriates to certify his degree. This was possible for a fee of JD5, whereas

Jordanian citizens pay only JD2

“We are being

treated as foreigners,” a frustrated Mohammad said.

There is no

recent data on the number of children to Jordanian mothers. But in 2014, the

Jordanian Ministry of Interior said that there were more than 355,000

non-Jordanians whose mothers were Jordanian citizens.

A report by the New

York-headquartered

Human Rights Watch said that those individuals usually

endure hardship in accessing basic rights and services. It said the authorities

also restrict their right to work, to own property, and to travel. They also

have limited access to public-funded education and healthcare.

The hardships

drove Jordanian mothers, who are married to foreigners, to stage protests and

sit-ins to draw attention to the discrimination against their children. This

included a campaign called “My Mother is Jordanian” and the coalition of “My

Right, My Family!”

Consequently, the

Cabinet said in 2014 that it was easing the restrictions by granting children

of Jordanian women some privileges.

But the

discretionary treatment was limited and did not meet the aspirations of the

children of Jordanian women, said Rami Al-Wakil, the coordinator of the “My

Mother is Jordanian” campaign.

“The privileges

and leeway are limited to certain areas and are not comprehensive. For example,

they are treated like Jordanians in primary and secondary education,” he

said. “When it comes to university

education, only 150 seats in public universities are reserved for the children

of Jordanian women on a competitive basis, while the rest are registered as

foreigners through the Parallel system.”

“In healthcare, children of Jordanian women up

to the age of 18 years are treated like Jordanians, but after that age, they

are treated as foreigners,” he added.

Human rights

activist Inaam Al-Asha said “Children of Jordanian women were given the ‘Package

of Citizenship Rights for Children of Jordanian Women’. This includes the right

to residency, work, education, and medical care, but not the right to political

participation.”

She said the

government move was a step towards reducing the hardships and difficulties

faced by the children of Jordanian women.

Is discriminating against children of Jordanian

mothers a constitutional violation?

Discrimination against the children of Jordanian women married to

foreigners happens despite the fact that the constitution guarantees their

mothers the right to equal treatment. Article (6) states, “Jordanians are equal

before the law, and there shall be no discrimination among them in rights or

duties regardless of their race, language or religion.”

The Jordanian

National Charter also stressed this right. It stated: “Jordanian men and women

are equal before the law; there shall be no discrimination among them in rights

or duties regardless of their race, language or religion.”

Some

constitutional amendments also went into force with the publication of the 2022

draft amendment to the Jordanian Constitution in the Official Gazette, issue

number 5,770.

The 14th

amendment to the

Jordanian Constitution of 1952 covered 25 articles in addition

to including the phrase “Jordanian women” in the title of Chapter Two of the

constitution. It was approved by the Senate and members of the Lower House of

Parliament.

Despite the

guarantees under the law, children of Jordanian women continue to suffer from

the discrimination of the law against their mothers, which deny them access to

basic services and opportunities, like other Jordanians.

Al-Asha, the

lawyer, said that “the constitution ranks top in the legal hierarchy. Other

laws, therefore, rank lower on the scale, and they cannot contradict the text

of the constitution.”

“However, this

constitutional amendment rendered the text at odds with the constitution, and

any such texts containing discriminatory language showing bias or inequality

among Jordanian men and women must be reconsidered,” she said.

Earlier this

year, the

Lower House of Parliament agreed to add the phrase “Jordanian women”

to the title of Chapter Two of the constitution, so that this title would

become “The Rights and Duties of Jordanian Men and Women.”

Citizenship maybe the answer to ending

discrimination

Human rights consultant

Riyadh Al-Suboh said that the solution lies in granting citizenship to the

children of Jordanian women, so they can enjoy all civil and political rights.

“The issue of the children of Jordanian women

is often discussed as a political and social matter, and is not seen from its

human rights perspective,” he said.

Asha said that

“civil society organizations are hoping that the amendment to the constitution

would warrant a reconsideration of the Jordanian citizenship law, as nothing

guarantees the rights and determines the duties like citizenship does, as it

seals the bond and regulates the relationship between a person and the country

in which he lived and grew up.”

Until a solution

that does justice to this category of people materializes, Ayham and other

children of Jordanian women married to foreigners continue to live in a country

they consider home, but are frustrated when they encounter discriminatory

situations.

“We are residents

of this country. We are citizens by emotional belonging, but not on official

papers,” Ayham said.

This story was previously published by ARIJ.

Read more Features

Jordan News