MADRID — “No foto!” was long the refrain

from guards at the Reina Sofía museum in Madrid if a visitor dared to attempt

to take a picture of “Guernica,” Pablo Picasso’s 1937 anti-war masterpiece. But

as one couple took a selfie Wednesday and another woman adjusted her hair while

smiling shyly into her phone’s camera, those guards were relaxed, offering tips

about audio guides rather than yelling.

اضافة اعلان

The museum lifted its longtime ban on

photos of “Guernica” this month, belatedly joining the Instagram era. Still

prohibited in Room 205.10 are the use of flash, tripods and selfie sticks, out

of concern that the 25-foot oil painting could be damaged.

“Allowing photographs to be taken of

‘Guernica’ is intended to enhance the experience of viewing the painting,

bringing it closer to the public and allowing what has been possible in other

museums for a long time,” a Reina Sofía spokesperson wrote in an email.

The spokesperson added, referring to

advances in technology, “The fact that the means have advanced and that they do

not endanger the work did not justify, at this point, the prohibition.”

Ten minutes after the museum opened its

doors Wednesday, about a dozen people gathered in front of “Guernica.” Many

stood close to the painting before shifting away for a different perspective.

Ronny de Jong, visiting from Rotterdam,

Netherlands, spent about 45 minutes taking in the work, a black-and-white

cubist painting that depicts the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and disturbed

those who saw it at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

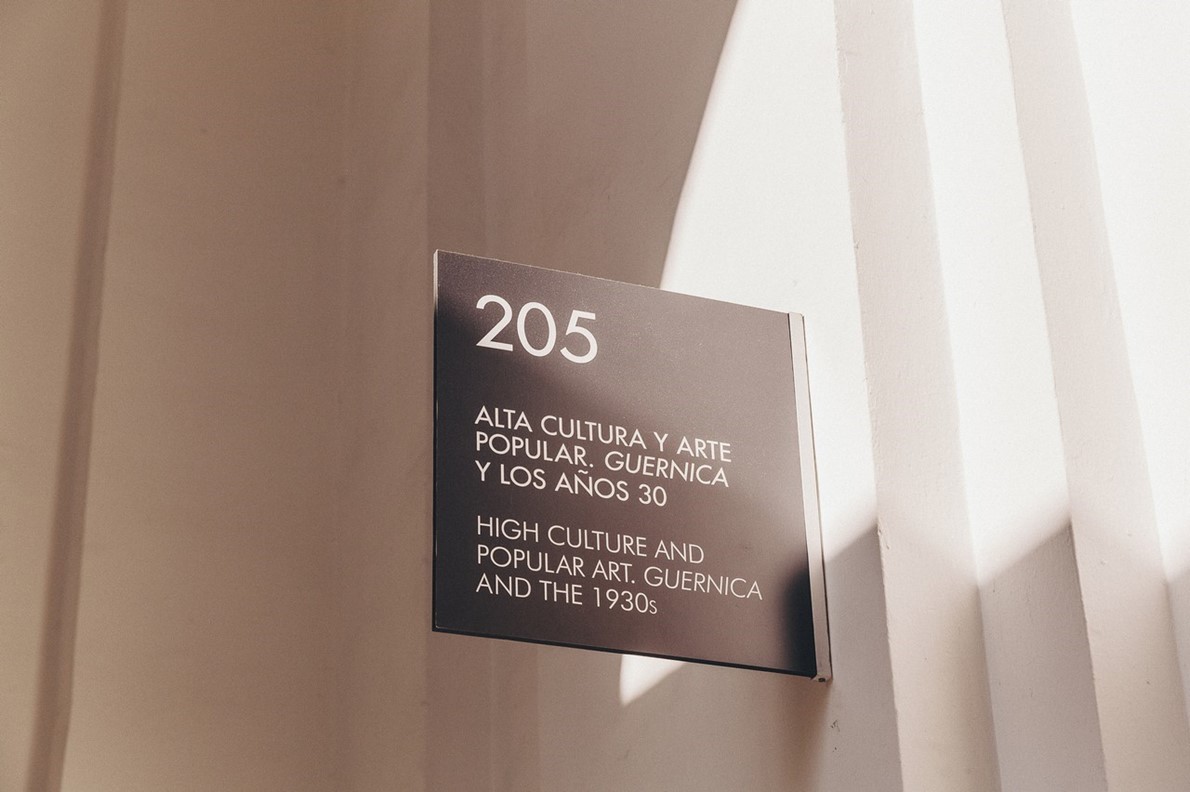

A sign in the Reina Sofía museum, home to

“Guernica,” Pablo Picasso’s 1937 antiwar painting in Madrid, Spain on Sept. 13,

2023.

A sign in the Reina Sofía museum, home to

“Guernica,” Pablo Picasso’s 1937 antiwar painting in Madrid, Spain on Sept. 13,

2023.

De Jong said he loved to remember his

museum visits through photos and that he was slightly annoyed that the nearby

Prado museum, home to many of Spain’s most important pre-20th-century artworks,

banned photographs altogether.

“I did make some pictures — like stealthily

— and no one was harmed,” he said.

Another visitor, Flavia Morelli of Rimini,

Italy, praised the Reina Sofía’s recent decision to allow photographs of

“Guernica.” “I think it’s a way to create a stronger link between people of

varying levels of culture and art,” she said.

The Reina Sofía did not explain the origins

of the ban on photographing one specific painting, but museums have long

struggled with how best to conserve artworks and manage resources while trying

to remain relevant to the public. For example, visitors cannot take photos

inside the Sistine Chapel in Italy, and photography and filming are prohibited

in some special exhibitions at museums because of copyright or lending

concerns.

Nina Simon, the author of “The

Participatory Museum,” said one reason museums originally banned photos was a

fear that people would not visit in person if they were able to see the images

online. That worry has abated, she said, but there is still genuine fear that

works could be damaged by distracted visitors, and that their photographs could

fundamentally alter museum programming.

“There becomes a concern that the museum

becomes the backdrop to your perfect Instagram life,” Simon said, “or that the

museum shifts the design of exhibits to cater to create great Instagram

moments, which could be seen as cheapening in some way.”

Along with the vocal guards, visitors to

the Reina Sofía have traditionally been separated from “Guernica” by a long

divider that spans the length of the artwork.

But the painting, which Picasso lent to the

Museum of Modern Art in New York for decades while Gen. Francisco Franco was in

power in Spain, has not always been so restricted. When it was on view at MoMA

in 1974, Tony Shafrazi, an artist who later became a successful art dealer,

sprayed “Kill Lies All” in red foot-high letters on the canvas.

The painting, which avoided permanent

damage because of a heavy coat of varnish, was returned to Spain in 1981.

Seema Rao, who leads Brilliant Idea Studio,

a firm that focuses on museum experiences, said museums must learn to keep up

with the demands of visitors who have traveled from around the world to see

works like “Guernica.” “If you can’t hold on to that, it doesn’t matter, it

doesn’t feel like it has value,” she said.

“Museums are basically becoming dinosaurs,”

Rao continued. “They are so behind the times. In order to be a part of society

they have to update these policies.”

One visitor at the Reina Sofía Wednesday,

Richard Rottman of Los Angeles, called “Guernica” an important Picasso shortly

after someone tapped his shoulder.

“I was in the way of their photo,” he said,

laughing.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News