AMMAN — Defying

challenging realities, three

Arab artists have come together, “linking” their

countries’ heritage and individual experiences to produce works and present

them to a public hungry for beauty and normality at an exhibition fittingly

called “3+1 Linking distances”.

اضافة اعلان

Held now at

Cairo Amman Bank Art Gallery, this traveling exhibition is the product of prominent

artists Mohammad Jaloos (Jordanian), Qassim Alsaedy (Dutch/Iraqi), and Salman

Al-Malek (Qatari) who, in 2019, while at an art symposium in Jordan, thought of

the idea, only to drop it under the onslaught of the pandemic.

Undeterred,

though, and showing the resilience man has in the face of adversity, they

worked, producing the artworks now on display in Amman and that will gradually

move to Doha, hosted by al markhiya gallery, and to the Netherlands, at

Frank Welkenhuysen Art Gallery. Plans are to then travel to other countries, in each

selecting a local artist to join — hence the 3+1 in the name of the exhibition

— bringing together, thus “linking”, countries, artists, and viewers through

the universal language of art.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

At

CAB Art Gallery each artist is present with 10 works. The styles and media may differ, but a

harmonious line seems to link them all: the unique, yet common, experience of

each artist. These works are yet another link in the long chain of artistic

expression of mankind in this region, one that goes back for millennia and that

has inevitably left an imprint on art everywhere.

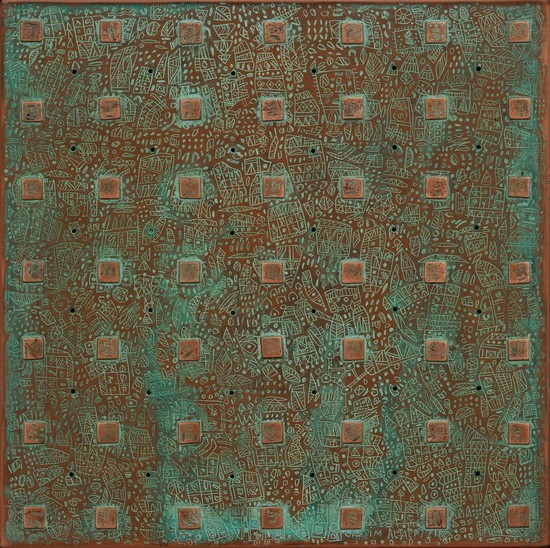

Alsaedy, who was

born in

Iraq and spent his childhood on the bank of the Tigris River, would

inevitably be influenced by the clay the river generously created and that, by

his own account, would be his first drawing book. Clay may have led this artist

to produce beautiful, colorful ceramics, including clay tablets reminiscent of

those on which, 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, humans would

write the first letters ever, but he uses different other media to create his

artworks. At this exhibition, he is present with stunning copper pieces that

draw the eye and held it glued to them.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

Square copper

sheets worked in relief but also incised hold arcane symbols and lettering.

Glinting, polished fragments drowned in a sea of verdigris attract like a

desert mirage, mysterious like some long-lost civilizations. Each piece abounds

with more smallish squares — regimented by an artist who finds the square a

perfect but challenging man-made shape and who knows that one extra or one less

would throw askew his whole endeavor — often surrounded by other geometric

images, less ordered, less “perfect” in shape.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

The works look, at

times, like aerial views of human settlements, of crowded metropolises with

their chaotic mazes of streets, buildings, and landscapes to which a measure of

discipline is imposed by the clean lines of squares attempting to regulate

hectic, bustling life.

Does the imagery,

the greenish color normally acquired by copper with age, suggest a new

civilization superimposed on older, long-gone others, a continuation, of life

and human development and thus a link between ancient and present?

Alsaedy’s works

will definitely link past and future, for they are deservedly part of the

patrimony of humanity.

Carrying on the

tenor, Malek’s works, acrylic on paper, present abstract imagery and hinted-at

calligraphy. The circular paintings with bold splashes of color are not allowed

to stray but are regimented in square frames.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

Thick brushstrokes

create abstract imagery in which one may decipher landscapes, natural and

manmade, stylized letters, and a jumble of amorphous life that seems to offset

Alsaedy’s well-ordered squares. Life, after all, is not a linear chain of

events, but an often accidental, unforeseen happening into which, at times,

Malek seems to want to infuse some order through lines, at different angles,

that intersect expanses of lighter color.

Are they the

imprint we leave behind, just like Alsaedy’s layers of human history? Are they

a rendition of some pristine expanse of the desert or of the Gulf water on

whose shores Doha sits?

The colors are

vivid and happy, yet black seems to dominate; after all, we live in the times

of

COVID-19 and life cannot be that cheerful. Still, the feeling with which one

leaves after watching his works is uplifting. They elicit calmness, herald the

advent of life as we knew it, are positive.

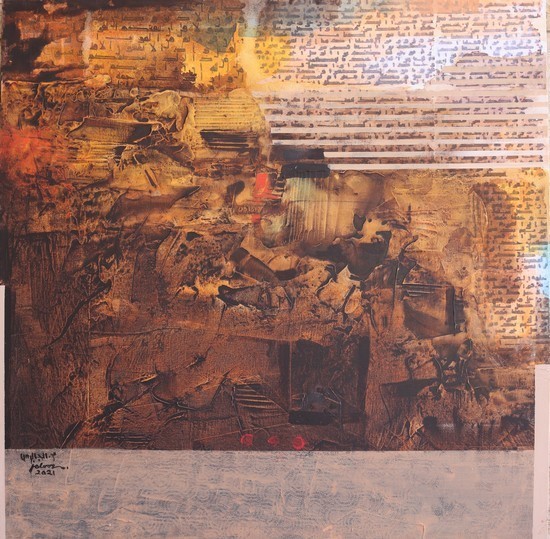

Maintaining the

thematic cohesion, Jaloos’ square paintings in striking desert colors — ocher,

beige, and all spectrum of brown – hold imagery that ranges from minimalistic

to crowded, from perfectly delineated to blurred.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

The mostly

monochromatic background looks immaculate from afar. At a closer look, however,

barely there carved or impressed traces are visible, just like the marks humans

leave on nature and posterity attempts to decipher.

The ochre

background is constant in

Jaloos’ works, but his calligraphy fades from sharp

to barely readable to illegible, slowly disintegrating to become inorganic

amorphous matter, abstract imagery that gradually loses identity, landscapes,

and then again assume life forms in a perpetual life cycle.

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

(Photo: Handouts from CAB Art Gallery)

Yet again one

senses layers of civilizations, sees messages that await decoding, is awed by

the mastery of the painter and by the coherence with which these three

different artists managed to come together and speak a common language, create,

in the words of curator, art appraiser, and collector Welkenhuysen, who

accompanied Alsaedy to Jordan, “artwork with a soul”.

The exhibition, which will undoubtedly touch every viewer’s

soul, is on until March 8.

Read more Culture and Arts