What makes a design a classic? New products flood the market

every year, yet very few have long lives and lasting impact. The lounge chair

designed by Charles and Ray Eames is as coveted today as it was in 1956, the

year it was introduced. (Probably even more so.) Richard Sapper’s Tizio table

lamp has illuminated the workspaces of thousands of users who were born after

it made its first appearance in 1971. Both products are enshrined in museums.

اضافة اعلان

“A classic is something beautiful that can be acknowledged

by everyone,” said Maria Cristina Didero, a Milan-based design curator and

author. “But what is classic design to experts may be different from what

people see who just want to furnish a home with beautiful objects.”

Didero assigned to the first category Bruno Munari’s Chair

for Very Brief Visits, a piece designed in 1945 that has a sloped seat that is

uncomfortable to perch on and is therefore more of a philosophical meditation

about furniture than anything you would offer to a guest.

And definitions of classics change over time, she said. A

coat rack produced by Italian company Gufram, in 1972, in the shape of a cactus

earned its stature because it rebelled against conventional tastes. Today, it

is celebrated as a cheerful piece of pop art.

In whatever way consensus is reached, there is little

argument about the works that furnish the pantheon of golden oldies. But what

about recently produced designs? Which will be classics down the road?

Didero nominated the Bilboquet lamp by British Canadian

designer Philippe Malouin, a flexible table light assembled with magnets that

was previewed at the 2023 Milan Furniture Fair and will be available next year

from Flos. “It’s a good combination of present sensibilities and past

masterpieces,” she said, finding echoes of Italian master Vico Magistretti’s

1965 Eclisse lamp.

She also gave a shout out to Candy Cubes (2014), chunky,

geometric tables by Netherlands-based designer Sabine Marcelis. “I like Sabine’s

work as it is refined and pure, and her interpretations of colors and finishes

are unique,” she said.

“It’s difficult to say what will be classics in the future,”

said Giulio Cappellini, a designer and art director who helped launch the

careers of Jasper Morrison, Tom Dixon, Marcel Wanders and many other

contemporary design stars. “In the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, there were really

classics and high concepts, but in the last few years there are many nice

products but it’s hard to find strong products.”

An exception is British architect Norman Foster’s minimal

Ixa light from Artemide (2022), which Cappellini finds “quite interesting; it

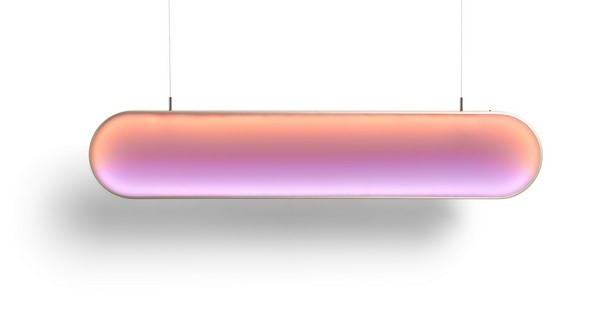

could be the new Tizio.” He also singled out Wanders’ recent Skynest pendant

light with woven LED strips from Flos as “a very contemporary interpretation of

an old chandelier. It’s something new in technology, and it’s also a beautiful

image.”

But his No. 1 pick was the Alfi chair designed by Morrison

for American furniture company Emeco (2015), which consists of fully recycled

materials, including polypropylene mixed with wood fiber, and is already in the

permanent collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. “Alfi is

an honest product, simple and timeless,” he said.

(Alfi was also the choice of design entrepreneur and author

Murray Moss, who said, “I’m almost surprised that I didn’t see it coming. It’s

so correct in so many ways.”)

Kathryn Hiesinger, a senior decorative arts curator at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, laid down her criteria for classics in simple

terms: “I prize originality and quality,” she said. “Trained as an art

historian, I think in terms of historical, cultural and technological

significance as well as aesthetic achievement.”

Hiesinger said she would select almost any of Naoto Fukasawa’s

products for Muji. (The museum is planning a Fukasawa show for 2024, Hiesinger

said.) The Japanese designer’s appliances — and his toaster above all else —

are ordinary objects that have been transformed into collectible art with “a

clean-lined simplicity of form, surface and meticulous functionality that make

them both anonymous and universal,” she said. “Perhaps they are the best

expression of Bauhaus functionalism.”

Her colleagues Colin Fanning and Alisa Chiles, assistant

curators in the museum’s European decorative arts and sculpture department,

voted for Danish design firm GamFratesi’s midcentury-inspired Beetle chair

(2013), the remote-controllable Stagg EKG electric kettle by San Francisco

company Fellow and a steel outdoor furniture collection called Palissade, by

French brothers Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec.

At least one expert prized environmental factors above all

others when considering designs that deserved to last. “There are a lot of

beautiful things, but what will make a real difference?” asked Aric Chen,

director of Het Nieuwe Instituut, a museum of architecture, design, and digital

culture in the Dutch city of Rotterdam. “It is not necessarily about objects,

but the way we produce objects — rethinking life cycles.”

Chen proposed Sunne, a solar-powered aluminum window lamp by

Marjan van Aubel that first appeared as a Kickstarter campaign in 2021.

“What will become classics of our time will be a mix of craft-forward

objects, as well as products that may not appeal to the masses but have cult

followings,” said Asli Altay, head of communications and content at the Walker

Art Center in Minneapolis. She specified handmade wood dolls that transmit

music, designed by Teenage Engineering, a group of young Swedes. She also

praised the construction of Nigerian designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello’s M2 shelf

made of African mahogany and powder-coated steel.

“To me, a classic has three qualities,” said Bobbye

Tigerman, curator of decorative arts and design at the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art. “It reflects the time in which it was made, it demonstrates

outstanding craftsmanship, and it has a timeless visual appeal.” Her pick: the

Nyala chair by Jomo Tariku, which signals the designer’s Ethiopian heritage and

his concern for antelope native to the Bale Mountains in that country. Nyala’s

organic curves “give it a timeless visual allure,” she said.

Gus Casely-Hayford, director of the V&A East Museum,

which is scheduled to open in his home base, London, in 2024, saw practicality

as the foundation for future recognition. “I live in a city with 9 million

people and over 3 million cars,” he said. “It’s impossible to get around. You

start to think about having a bike, but so often people find them stolen.”

Which is why he nominated the Brompton electric bicycle,

first introduced in 2017. “Small and compact, it folds down to the size of a

piece of luggage that you might take with you on a plane, but it can be ridden

by anyone of any size,” he said. “Bikes were originally designed in the 1880s.

This is a foldable, electric, timeless invention that feels incredibly timely.”

Marc Benda, co-founder of Friedman Benda in Manhattan, which

deals in limited-edition designs, pleaded guilty to self-interest when he

singled out the Trauma Chair (2020) by Samuel Ross, a British industrial and

fashion designer his gallery represents. “The chair, which has already entered

the collections of two museums, is really a reaction to the events of three years

ago,” Benda said, referring to the protests after the killing of George Floyd

by a police officer. “It’s a Black voice addressing issues of social justice.”

Though his gallery objects are not widely available, Benda

said, they should still qualify for admission into the canon of classics. “They

can be seen and appreciated in museums and on Instagram,” he said. “It’s not

only about acquiring.”

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News