The secrets lurking inside Matisse’s ‘Red Studio’

New York Times

last updated: Aug 28,2022

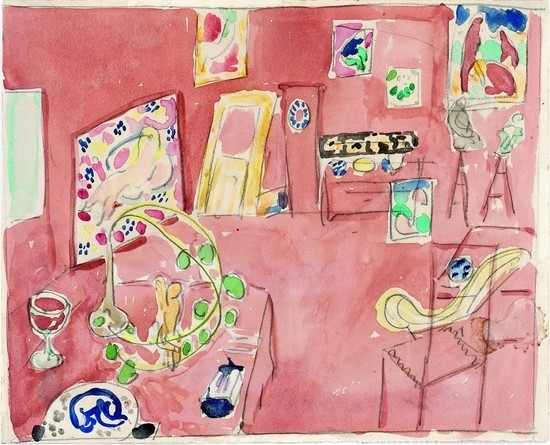

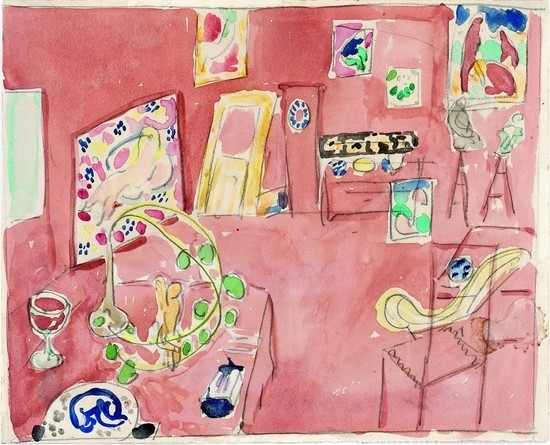

NEW YORK, United States — A flowered dress. A naked teenager. A Russian millionaire. A fancy room that hides secrets.

Sounds like

promotional copy for a true-crime drama, but I recently spotted its plot in an

icon of modern art, “The Red Studio,” painted in 1911 by Henri Matisse. That

huge canvas, portraying the fancy atelier that Matisse had just built for

himself and the artworks that hung in it, is the subject of a brilliantly

focused exhibition now at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). My colleague Roberta

Smith described “Matisse: The Red Studio” as “spectacular” when it opened in

May, and I couldn’t agree more. Art lovers will want to catch the exhibition,

or catch it again and again, before it closes September 10.

I had seen “The

Red Studio” before — it has lived at MoMA for decades — but it took me three

visits to this latest show to winkle out a story that, for something like 100

years now, has lain camouflaged beneath the painting’s red surface.

Almost since the

day it was painted, that surface has been seen as the heart of the work. It was

supposed to teach us to leave behind the deep space of old master pictures and

love modern art’s flatness instead. Starting somewhere around 1900 — and partly

thanks to Matisse — paintings started to be read for the colors, lines, and

shapes that are right there for us to see, rather than for any scene that we

might look beyond them to understand. In the excellent catalog for the MoMA

show (those who cannot visit should buy it), curators Ann Temkin and Dorthe

Aagesen talk about “a bold new planarity” that turns “The Red Studio” into “an

indisputable landmark” in the modern trend toward abstraction. Matisse himself

originally titled the picture nothing more than “Red Panel,” as if color and

flatness were its true subject.

That flat-talk has

always been right, but on my several visits to “Matisse: The Red Studio,” I

started to appreciate another dimension — a different vector, you might say —

that is at least as important as the one that sees our glance going no deeper

than the painting’s redness. My new “vector” instead lives far inside the

studio’s depicted space, crossing from the huge painting of a female nude that

Matisse shows on its left-hand wall to the empty rattan chair that faces it at

far right, standing out in bright yellow when the room’s other furnishings are

swallowed in the painting’s red.

I got a clue to

what might really be going on in the scene from the daisies that Matisse

floated around his nude.

I had seen those

flowers before, in reproductions of “The Painter’s Family,” a slightly earlier

Matisse that lives at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia: They were all

over the dress of a teenage girl who sits doing needlework toward its rear.

And there those

flowers were yet again, in the MoMA show, surrounding the naked girl who

figures in a series of sketches Matisse did for the nude that fills that wall

in “The Red Studio.” A wall text revealed who she was: Marguerite — French for

“daisy” — Matisse’s eldest child, who, at the age of 16 or maybe just 17, had

posed for the canvas, later known as the “Large Nude,” that her father had

given such play to in his studio scene.

I think Matisse

meant his daughter’s naked image to be the true focus of “The Red Studio,” or

at least its hidden theme. That empty rattan chair invites us to venture into

the depths of the scene and take in its nude at our leisure; Matisse has even

set an ashtray or candy dish near at hand, for our added comfort.

But maybe

Matisse’s invitation does not really extend to us, today’s viewers of the

painting at MoMA, so much as to a single man in its past: Sergei Shchukin, a

Moscow textile magnate who had commissioned the picture for his mansion and who

would have been its first and principal viewer. It was Shchukin’s extravagant

patronage that had allowed Matisse, barely emerging from bohemian poverty, to

afford the custom-built studio outside Paris that his painting depicts, and to

finally move his long-suffering family into the comfort of a fine house next

door. You could say that “The Red Studio” celebrates a subject that never

appears on its surface: the man who had made it possible for that studio to

exist.

Today, we recoil

at the thought of a 41-year-old dad sketching his naked teenager just so a

Russian tycoon can then ogle her body, almost like a thank-you gift from artist

to patron. But in the utterly sexist, patriarchal world of Europe before World

War I, Matisse’s sessions with his daughter do not seem to have raised red

flags: He was quite happy to write to his wife about them.

By 1911,

Marguerite had modeled for both Matisse and his friends, so her role in “Large

Nude” might have seemed almost par for the course.

She had also

played a vital, almost maternal role in running the chaotic Matisse household,

and so might have come across as pretty much an adult, in an era when childhood

did not last all that long. There is certainly no hint that anything improper

had gone on during the drawing sessions, at least by the weak standards then in

force. And, within the logic of Matisse’s art at that moment, he absolutely

needed to base his nude on Marguerite, rather than on some model brought in

from outside the family circle.

In “The Red

Studio,” Matisse took the homemaking Marguerite of his family painting,

identified there by the “marguerites” on her dress, and translated her into his

atelier’s artful nude, still recognizably daisied. A central figure from

Matisse’s home life, that is, gets to play double duty as a symbol of the grand

European tradition. He’s telling us that domesticity is still at hand in the

new picture, however much art and its evolution might also be in play.

For all the riotous style

in “The Red Studio,” Matisse imagined that it might someday become family fare.

Judging by the untroubled pleasure his painting gives us at MoMA, he succeeded.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_509089081')

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_552628228')

Read More

Developments in the Health Condition of Egyptian Actress Abla Kamel

Jumana Murad Reveals Her True Age

"Pray for Me" - Mohamed Sami Announces Retirement from TV Drama Directing

NEW YORK, United States — A flowered dress. A naked teenager. A Russian millionaire. A fancy room that hides secrets.

Sounds like promotional copy for a true-crime drama, but I recently spotted its plot in an icon of modern art, “The Red Studio,” painted in 1911 by Henri Matisse. That huge canvas, portraying the fancy atelier that Matisse had just built for himself and the artworks that hung in it, is the subject of a brilliantly focused exhibition now at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). My colleague Roberta Smith described “Matisse: The Red Studio” as “spectacular” when it opened in May, and I couldn’t agree more. Art lovers will want to catch the exhibition, or catch it again and again, before it closes September 10.

I had seen “The Red Studio” before — it has lived at MoMA for decades — but it took me three visits to this latest show to winkle out a story that, for something like 100 years now, has lain camouflaged beneath the painting’s red surface.

Almost since the day it was painted, that surface has been seen as the heart of the work. It was supposed to teach us to leave behind the deep space of old master pictures and love modern art’s flatness instead. Starting somewhere around 1900 — and partly thanks to Matisse — paintings started to be read for the colors, lines, and shapes that are right there for us to see, rather than for any scene that we might look beyond them to understand. In the excellent catalog for the MoMA show (those who cannot visit should buy it), curators Ann Temkin and Dorthe Aagesen talk about “a bold new planarity” that turns “The Red Studio” into “an indisputable landmark” in the modern trend toward abstraction. Matisse himself originally titled the picture nothing more than “Red Panel,” as if color and flatness were its true subject.

That flat-talk has always been right, but on my several visits to “Matisse: The Red Studio,” I started to appreciate another dimension — a different vector, you might say — that is at least as important as the one that sees our glance going no deeper than the painting’s redness. My new “vector” instead lives far inside the studio’s depicted space, crossing from the huge painting of a female nude that Matisse shows on its left-hand wall to the empty rattan chair that faces it at far right, standing out in bright yellow when the room’s other furnishings are swallowed in the painting’s red.

I got a clue to what might really be going on in the scene from the daisies that Matisse floated around his nude.

I had seen those flowers before, in reproductions of “The Painter’s Family,” a slightly earlier Matisse that lives at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia: They were all over the dress of a teenage girl who sits doing needlework toward its rear.

And there those flowers were yet again, in the MoMA show, surrounding the naked girl who figures in a series of sketches Matisse did for the nude that fills that wall in “The Red Studio.” A wall text revealed who she was: Marguerite — French for “daisy” — Matisse’s eldest child, who, at the age of 16 or maybe just 17, had posed for the canvas, later known as the “Large Nude,” that her father had given such play to in his studio scene.

I think Matisse meant his daughter’s naked image to be the true focus of “The Red Studio,” or at least its hidden theme. That empty rattan chair invites us to venture into the depths of the scene and take in its nude at our leisure; Matisse has even set an ashtray or candy dish near at hand, for our added comfort.

But maybe Matisse’s invitation does not really extend to us, today’s viewers of the painting at MoMA, so much as to a single man in its past: Sergei Shchukin, a Moscow textile magnate who had commissioned the picture for his mansion and who would have been its first and principal viewer. It was Shchukin’s extravagant patronage that had allowed Matisse, barely emerging from bohemian poverty, to afford the custom-built studio outside Paris that his painting depicts, and to finally move his long-suffering family into the comfort of a fine house next door. You could say that “The Red Studio” celebrates a subject that never appears on its surface: the man who had made it possible for that studio to exist.

Today, we recoil at the thought of a 41-year-old dad sketching his naked teenager just so a Russian tycoon can then ogle her body, almost like a thank-you gift from artist to patron. But in the utterly sexist, patriarchal world of Europe before World War I, Matisse’s sessions with his daughter do not seem to have raised red flags: He was quite happy to write to his wife about them.

By 1911, Marguerite had modeled for both Matisse and his friends, so her role in “Large Nude” might have seemed almost par for the course.

She had also played a vital, almost maternal role in running the chaotic Matisse household, and so might have come across as pretty much an adult, in an era when childhood did not last all that long. There is certainly no hint that anything improper had gone on during the drawing sessions, at least by the weak standards then in force. And, within the logic of Matisse’s art at that moment, he absolutely needed to base his nude on Marguerite, rather than on some model brought in from outside the family circle.

In “The Red Studio,” Matisse took the homemaking Marguerite of his family painting, identified there by the “marguerites” on her dress, and translated her into his atelier’s artful nude, still recognizably daisied. A central figure from Matisse’s home life, that is, gets to play double duty as a symbol of the grand European tradition. He’s telling us that domesticity is still at hand in the new picture, however much art and its evolution might also be in play.

For all the riotous style in “The Red Studio,” Matisse imagined that it might someday become family fare. Judging by the untroubled pleasure his painting gives us at MoMA, he succeeded.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News

Sounds like promotional copy for a true-crime drama, but I recently spotted its plot in an icon of modern art, “The Red Studio,” painted in 1911 by Henri Matisse. That huge canvas, portraying the fancy atelier that Matisse had just built for himself and the artworks that hung in it, is the subject of a brilliantly focused exhibition now at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). My colleague Roberta Smith described “Matisse: The Red Studio” as “spectacular” when it opened in May, and I couldn’t agree more. Art lovers will want to catch the exhibition, or catch it again and again, before it closes September 10.

I had seen “The Red Studio” before — it has lived at MoMA for decades — but it took me three visits to this latest show to winkle out a story that, for something like 100 years now, has lain camouflaged beneath the painting’s red surface.

Almost since the day it was painted, that surface has been seen as the heart of the work. It was supposed to teach us to leave behind the deep space of old master pictures and love modern art’s flatness instead. Starting somewhere around 1900 — and partly thanks to Matisse — paintings started to be read for the colors, lines, and shapes that are right there for us to see, rather than for any scene that we might look beyond them to understand. In the excellent catalog for the MoMA show (those who cannot visit should buy it), curators Ann Temkin and Dorthe Aagesen talk about “a bold new planarity” that turns “The Red Studio” into “an indisputable landmark” in the modern trend toward abstraction. Matisse himself originally titled the picture nothing more than “Red Panel,” as if color and flatness were its true subject.

That flat-talk has always been right, but on my several visits to “Matisse: The Red Studio,” I started to appreciate another dimension — a different vector, you might say — that is at least as important as the one that sees our glance going no deeper than the painting’s redness. My new “vector” instead lives far inside the studio’s depicted space, crossing from the huge painting of a female nude that Matisse shows on its left-hand wall to the empty rattan chair that faces it at far right, standing out in bright yellow when the room’s other furnishings are swallowed in the painting’s red.

I got a clue to what might really be going on in the scene from the daisies that Matisse floated around his nude.

I had seen those flowers before, in reproductions of “The Painter’s Family,” a slightly earlier Matisse that lives at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia: They were all over the dress of a teenage girl who sits doing needlework toward its rear.

And there those flowers were yet again, in the MoMA show, surrounding the naked girl who figures in a series of sketches Matisse did for the nude that fills that wall in “The Red Studio.” A wall text revealed who she was: Marguerite — French for “daisy” — Matisse’s eldest child, who, at the age of 16 or maybe just 17, had posed for the canvas, later known as the “Large Nude,” that her father had given such play to in his studio scene.

I think Matisse meant his daughter’s naked image to be the true focus of “The Red Studio,” or at least its hidden theme. That empty rattan chair invites us to venture into the depths of the scene and take in its nude at our leisure; Matisse has even set an ashtray or candy dish near at hand, for our added comfort.

But maybe Matisse’s invitation does not really extend to us, today’s viewers of the painting at MoMA, so much as to a single man in its past: Sergei Shchukin, a Moscow textile magnate who had commissioned the picture for his mansion and who would have been its first and principal viewer. It was Shchukin’s extravagant patronage that had allowed Matisse, barely emerging from bohemian poverty, to afford the custom-built studio outside Paris that his painting depicts, and to finally move his long-suffering family into the comfort of a fine house next door. You could say that “The Red Studio” celebrates a subject that never appears on its surface: the man who had made it possible for that studio to exist.

Today, we recoil at the thought of a 41-year-old dad sketching his naked teenager just so a Russian tycoon can then ogle her body, almost like a thank-you gift from artist to patron. But in the utterly sexist, patriarchal world of Europe before World War I, Matisse’s sessions with his daughter do not seem to have raised red flags: He was quite happy to write to his wife about them.

By 1911, Marguerite had modeled for both Matisse and his friends, so her role in “Large Nude” might have seemed almost par for the course.

She had also played a vital, almost maternal role in running the chaotic Matisse household, and so might have come across as pretty much an adult, in an era when childhood did not last all that long. There is certainly no hint that anything improper had gone on during the drawing sessions, at least by the weak standards then in force. And, within the logic of Matisse’s art at that moment, he absolutely needed to base his nude on Marguerite, rather than on some model brought in from outside the family circle.

In “The Red Studio,” Matisse took the homemaking Marguerite of his family painting, identified there by the “marguerites” on her dress, and translated her into his atelier’s artful nude, still recognizably daisied. A central figure from Matisse’s home life, that is, gets to play double duty as a symbol of the grand European tradition. He’s telling us that domesticity is still at hand in the new picture, however much art and its evolution might also be in play.

For all the riotous style in “The Red Studio,” Matisse imagined that it might someday become family fare. Judging by the untroubled pleasure his painting gives us at MoMA, he succeeded.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News