NEW YORK, US —

Beethoven’s only opera, “Fidelio,” is hardly a

fixed text. He wrote several possible overtures for it and reworked the score

substantially over the course of a decade. But its meaning never changed: the

heroism to be found in devotion, love, and freedom in the face of injustice.

اضافة اعلان

In 2018, the

daring and imaginative Heartbeat

Opera — an enterprise that, while small and

still young, has already contributed more to opera’s vitality than most major

American companies — took the malleable history of “Fidelio” one step further,

adapting the work as a moving indictment of mass incarceration.

That production

has now been revised for a revival that opened at the Grace Rainey Rogers

Auditorium at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art last weekend, before a tour that

continues through the end of the month. Already inspired by the Black Lives

Matter movement, this “Fidelio” is now permeated with it, and the adaptation is

even more powerful.

In Beethoven’s

original singspiel — a music theater form in which sung numbers are set up by

spoken scenes — a woman named Leonore disguises herself as a man, Fidelio, to

infiltrate the prison where her husband, Florestan, is being held for political

reasons. She aims to free him from execution while exposing the crimes of his

captor, Pizarro.

(Photo: NYTimes)

(Photo: NYTimes)

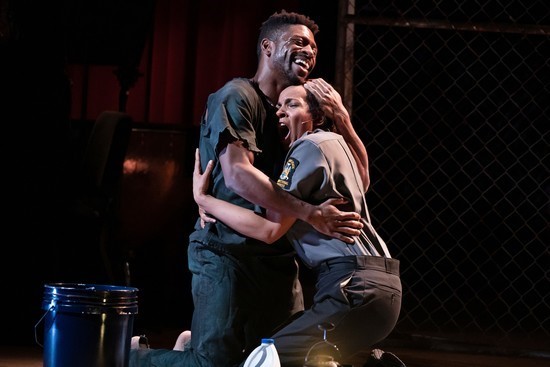

Ethan Heard,

co-founder of Heartbeat, adapted “Fidelio” for the company and collaborated

with playwright Marcus Scott on the new book. Their revision tells the story of

a

Black Lives Matter activist named Stan — sung by Curtis Bannister, a tenor of

impressive stamina — who has been imprisoned for nearly a year, and whose wife,

Leah, given an affectingly agonized lower range by soprano Kelly Griffin, is at

a breaking point as she struggles to free him.

She gets a job as

a guard at the prison; her strategy to reach Stan in solitary confinement (much

as in Beethoven’s original) is to ingratiate herself with a senior guard (here

Roc, sung with both charm and dramatic complexity by bass-baritone Derrell

Acon) and court his daughter (here Marcy, smooth-voiced yet strong in soprano

Victoria Lawal’s portrayal). In this telling, crucially, all of these

characters are black, a fact that looms before guiding the awakenings of Marcy

and her father as they face their complicity in a racist system that, Leah

says, is designed to punish “people whose only mistake was being poor and black.”

The spoken text is

in English throughout, while the arias remain in their original German — a

testament to the timelessness of Beethoven, although the production’s surtitles

take some liberties with the translation. (As an excuse for briefly letting the

prisoners out into the sun, Roc sings that it’s the king’s name day, but the

titles say that it’s

Martin Luther King Jr. Day.)

Radically

transformed, too, is the score, arranged by Daniel Schlosberg for two pianos,

two horns, two cellos, and percussion, with the multitasking (and nearly

scene-stealing) Schlosberg onstage, conducting from the keyboard. Expressive

cellos reveal the characters’ thoughts, and the horns add an aura of

muscularity and honor. The most substantial interventions are in the

percussion, with drum hits deployed to dramatic effect, and a whiplike slap

adding terror to Pizarro’s murder-plotting “Ha, welch’ ein Augenblick.”

(Photo: NYTimes)

(Photo: NYTimes)

Not all the changes

from 2018 were necessary or wise. Starting with the venue: This production

originated in a black box space at

Baruch Performing Arts Center, which fit the

chamber scale of the music and emphasized the cinder-block claustrophobia of

Reid Thompson’s set. At the Met, the show floats on an expansive stage and

struggles with poor acoustics.

And the text has

lost some of its grace, with pandering references to the January 6, 2021,

insurrection and President Donald Trump’s infamous call for the Proud Boys to

“stand back and stand by.” A casualty of these lapses is baritone Corey

McKern’s Pizarro, who is something of a Trump stand-in, a caricature among

nuanced, human characters.

You could almost

forgive that at “O welche Lust,” the famous prisoners’ chorus, still the

emotional high point of the production and now a coup de theatre. For the

stirring number, Leah unlocks a chest — a metaphor for the prison gates — to

release a white screen, on which a video is projected, featuring 100

incarcerated singers and 70 volunteers from six prison ensembles. The camera

often lingers on individual faces, to an effect not unlike that of Barry

Jenkins’ filmmaking, the way his sustained close-ups invite intimacy and, above

all, sympathy.

For curious

audience members, Heartbeat has shared letters from some of the participants.

They range from endearing — Michael “Black” Powell II’s “German was hard!!” —

to profound, such as this from Douglass Elliott: “Most of us are victims of our

circumstances who when faced with adversities chose the wrong direction with

our actions. This choir makes us feel that ‘normal’ feeling for a short time

every week. We are accepted as humans, not looked at as numbers.”

(Photo: NYTimes)

(Photo: NYTimes)

Beethoven’s

triumphant finale could have been an insult to the contemporary reality

Heartbeat’s production aims to conjure. So, after Stan is freed and Pizarro

defeated, Leah awakes at the same desk where, in the opening, she has had a

frustrating phone call with a lawyer. This twist — that it was all a dream —

is, of course, a tired trope, but what follows isn’t.

After a moment of despair

— her happiness felt so real — she stands, steps to a spotlight at center stage

and holds up her phone, assuming the pose of her husband’s activism, with which

the production began. An ambivalent closing scene, it is an honest reflection

of our time: of the mixed successes of Black Lives Matter, yes, and of the only

possible way forward.

Read more Entertainment