The proliferation of documentaries on streaming

services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Here are three nonfiction

films that will reward your time.

اضافة اعلان

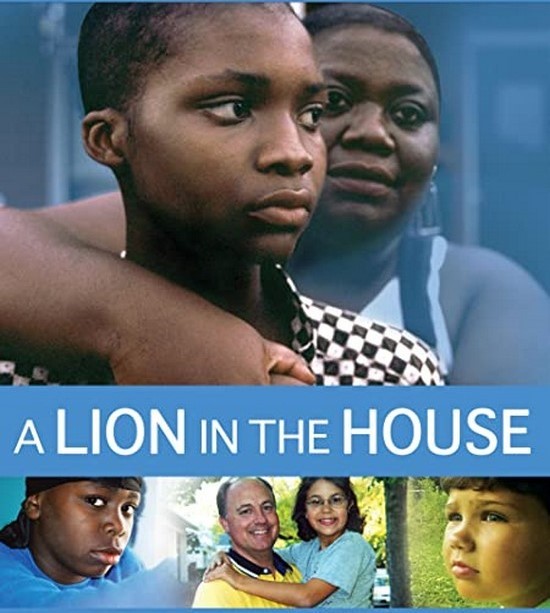

‘A Lion in the House’

(2006)Stream it on Netflix.

(Photos: IMDB)

(Photos: IMDB)

When documentarian Julia Reichert (“American Factory”) died

this month, her obituary in The New York Times called “A Lion in the House” her

most personal film. Directed with her husband and filmmaking partner, Steven

Bognar, the documentary began when, according to Bognar’s opening narration, they

were invited by the head oncologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital to make a

documentary about what a family goes through when a child has cancer. In the

voice-over, Reichert notes that their own daughter had just finished treatment

for cancer. After the movie was finished, Reichert received a diagnosis of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Made over six years, the documentary pivots around 5A, the

cancer unit at the pediatric hospital. For nearly four hours of screen time, it

immerses viewers in the lives of five patients who received their cancer

diagnoses as children, and in the lives of their families and the many doctors,

nurses, and social workers charged with their care. While a

film such as

Frederick Wiseman’s extraordinary “Near Death” (1989) approached the subject of

mortality with intimacy but a characteristic detachment, “A Lion in the House”

is a case in which the filmmakers have a clear emotional investment in the

material. Few documentaries look so unflinchingly yet so compassionately at the

cruelty of relentless medical ordeals.

The patients vary in their circumstances and prognoses. They

include Tim, a teenager with Hodgkin lymphoma, who initially resists his

doctors’ efforts to have him gain weight and whose illness has severely limited

his social life and his attendance at school. Alex, who has leukemia, is

introduced when she is 7 and her cancer is in remission, but it returns, and

Reichert and Bognar follow her and her at-times disagreeing parents through a

succession of tough decisions on treatment, in which the answers about what’s

best for Alex and what might prolong her survival are not always clear. Justin,

at 19, has already been fighting leukemia for 10 years when the movie begins;

over the course of the film, he reaches what appears to be the end, with at

least one doctor pushing for a serious discussion about his death. But when

Justin somehow survives after 24 hours of having what another doctor calls

“blood pressures incompatible with life,” the parents’ decision on whether to

press on for their professed fighter of a son only grows thornier.

Every moment in the movie is the stuff of life and death,

and while “A Lion in the House” is almost always tough to watch, it is also

impossible to shake.

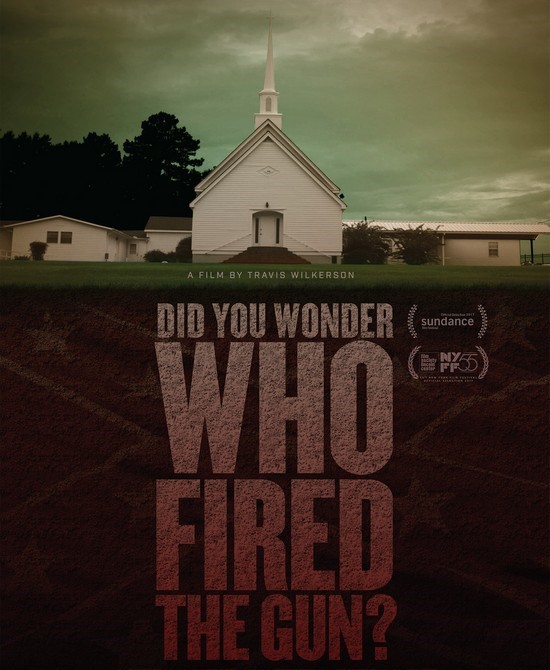

‘Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun?’ (2018)Stream it on Fandor, Kanopy, Ovid, Projectr, and Topic. Rent

it on Amazon and Apple TV.

The protests following the acquittal of

George Zimmerman in

the killing of Trayvon Martin prompted experimental filmmaker Travis Wilkerson

to investigate a troubling family story. He had been told S.E. Branch, his

great-grandfather, who ran a grocery store in Dothan, Alabama, and was, from

what we hear of him, a virulent racist, had killed a Black man, Bill Spann, in

the 1940s and gotten away with it.

Wilkerson’s mother quickly sends him a newspaper item from

1946; it says that there was a charge against Branch for first-degree murder in

Spann’s killing. But that charge mysteriously disappeared, as tended to happen

when white men committed violence against Black people in the Deep South, and

Branch went on to live for decades. Wilkerson pores images of him in 8mm home

movies, one of which is labeled with the month of the murder. He even has a

photo of the two of them together, the year Wilkerson was born and Branch died.

As for Spann, there are few traces left of him or any descendants. “Did You

Wonder Who Fired the Gun?” is partly the

filmmaker’s effort to atone for that

absence. To paraphrase his voice-over, this is the story of a murder victim

buried in an unmarked grave — and of the killer’s great-grandson, who is

filming that grave. “That’s a pretty precise expression of racism, no matter

how you cut it,” Wilkerson narrates.

The scope of this chilling essay film is much broader than

Wilkerson’s family history and his sleuthing. Wilkerson meets with Edward

Vaughn, a civil rights activist from the area who remembers a boycott of

Branch’s grocery store after the killing and the woeful conditions at the

hospital where Spann had been taken. Wilkerson weaves in an account of the rape

of Recy Taylor — an assault that took place nearby in 1944 — and the work that

Rosa Parks, roughly a decade before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, did to

investigate it.

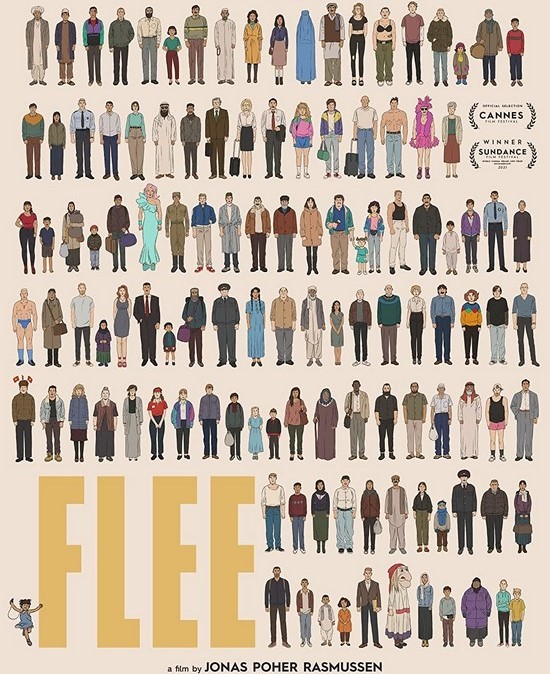

‘Flee’ (2021)Stream it on Hulu.

“Flee,” from director Jonas Poher Rasmussen, received Oscar

nominations for both animated feature and documentary — an unusual combination.

But animation really is the ideal form for this nonfiction account of one

refugee’s flight from Afghanistan in the early 1990s. One of the themes that

emerges is that living clandestinely requires continually being able to adapt

one’s identity. In that way, the abstraction of animation — its distance from

reality — reflects the material.

The central figure of “Flee” is called Amin in the film (at

the start, the

documentary notes that certain names and locations have been

altered to protect the subjects). He knew Rasmussen from high school, but there

is a lot that Rasmussen did not know about him. As Amin’s interlocutor

throughout the feature, the director, interviewing him in Copenhagen, gets him

to divulge things that he has largely kept to himself, for understandable

reasons. Amin gives an account of a journey from Afghanistan that was anything

but straightforward: He speaks of arriving in Moscow the year after the fall of

the Soviet Union and an arduous effort to escape that eventually returned him

to Russia, for a time.

You might be tempted to see Amin’s resilience as inspiring,

but in “Flee,” he also considers the lingering effects his experiences on the

run have had on his personality. “When you flee as a child, it takes time to

learn to trust people,” he says. “You’re constantly on your guard.” The sense

given is that his defensive mode may have even caused friction in his present

relationship. The film also deals with Amin’s coming to terms with being gay —

he says there wasn’t even a word for it in

Afghanistan — and his fears of his

family’s reaction. But that outpouring — more of a blurting-out — makes for one

of the film’s most unexpected and

heartwarming sequences.

Read more Entertainment

Jordan News