SEOUL —

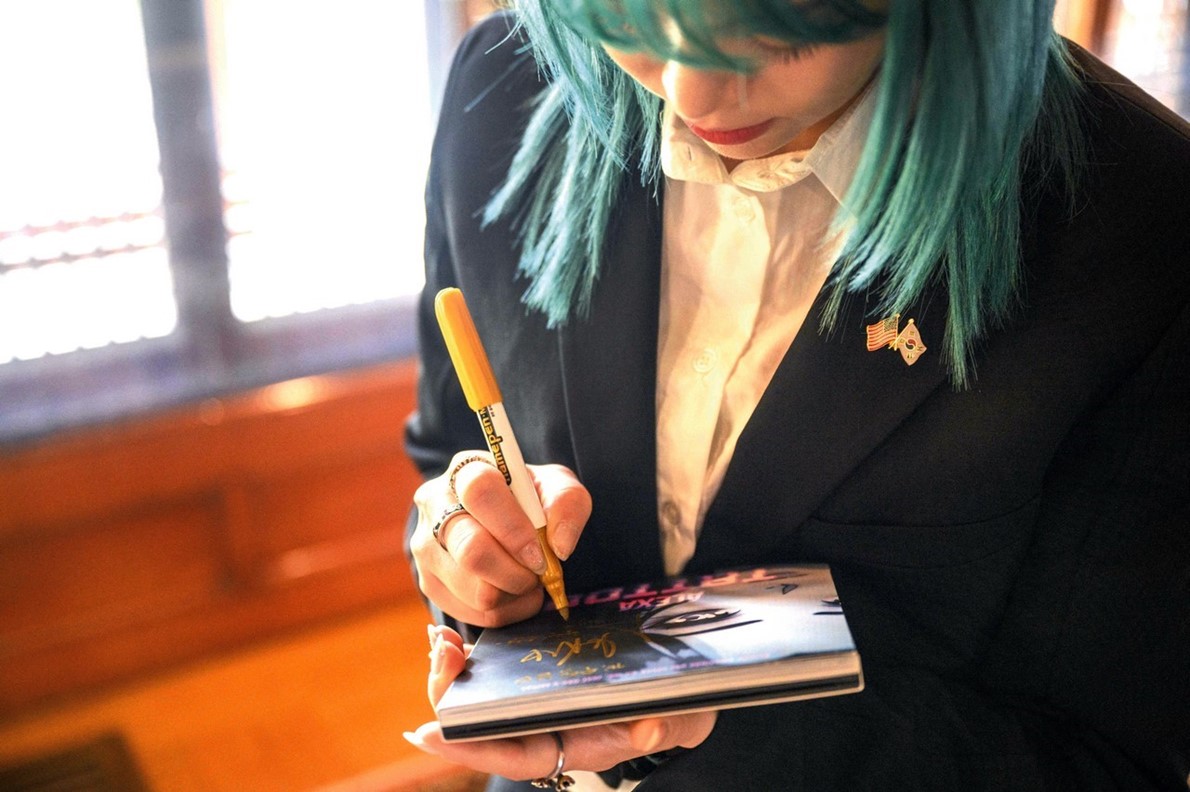

Korean-American

K-pop star AleXa has wanted to be on stage since she was a kid,

but her search for fame in South Korea was also fuelled by another reason — to

help her mother find her birth family.

اضافة اعلان

Adopted from South

Korea by an American family, her mother knows little about her birth culture

nor does she speak the language.

The blue-haired

25-year-old who recently won the

American Song Contest — the US version of

Eurovision — told AFP that eating kimchi was one of her few cultural links to

her Korean heritage growing up.

That is, until

AleXa discovered K-pop in 2008.

“That kind of

sparked my dream and my drive to become a K-pop artist,” said the Tulsa-born

rising star, who has been dancing since she was two.

Growing up in

Oklahoma, AleXa said seeing entertainers on-screen she could identify with as a

Korean American showed her “an interesting path to follow”.

At university, she

took home the top prize at a K-pop competition — a trip to South Korea to film

a reality show where she met executives from her future company and entered the

grueling star-making training so many young hopefuls embark on.

Like many adoptees, she would like to trace her birth family, but “The laws here in Korea are a little strict regarding if the child can find their birth parents and vice versa.”

She moved to Seoul

in 2018 and — having never spoken it while growing up — studied Korean at an

academy for a few months, continuing her lessons by watching movies and TV

shows while undergoing intensive dance classes.

Search for family

While AleXa has found success as a K-pop idol, her quest to find her

mother’s family is proving to be a more arduous process, foiled by

South Korea’s restrictive adoptive laws.

Born in Ilsan,

northwest of Seoul, her mother was adopted when she was five.

Like many adoptees,

she would like to trace her birth family, but “the laws here in Korea are a

little strict regarding if the child can find their birth parents and vice

versa,” AleXa said.

South Korea places

the right to privacy of the birth parent above the rights of the adoptee.

The country has

long been a major exporter of overseas adoptees, with hundreds of thousands

sent away since the 1950s.

After the

Korean War, it was a way to remove children — especially those born to local mothers

and American GI fathers — from a country that emphasizes ethnic homogeneity.

Even today,

unmarried pregnant women still face stigma in a patriarchal society and are

often forced to give up their babies.

“The opposite party

must be in search of the other in order for the first party to gain

information,” the singing star said.

That has not

happened in their case, so her mother is still unable to find AleXa’s grandma.

However, she has

had some success through the internet and DNA testing, and found some cousins

in other countries.

AleXa said they

haven’t given up hope.

“Hopefully in the

future, we can find some of my Korean family here. It would be nice,” she told

AFP, adding that she now considers Seoul her “second home”.

Representation

When NBC decided to put together the American version of the Eurovision

song contest, AleXa — “a Eurovision fan” — was invited to enter to represent

her home state.

It gave her and her

team a chance to bring K-pop to American audiences, and they immediately began

planning.

“How can we do

staging, what concept would work, what would really grab the American audience

while staying true to the K-pop?” she told AFP of their process.

Beyond nationality

or language, for AleXa, K-pop is a commitment to concept, styling and execution

— the hair and make-up, sets, staging and cinematography must be perfect.

“I really enjoy,

you know, the spectacle, the art, the wonder, the beauty that is K-pop,” she

said.

For her American

Song Contest finale, AleXa descended from the rafters to the stage on a throne,

then launched into choreography of military precision with her dancers as she

sang “Wonderland”.

Her win has K-pop

fans applauding her for bringing the genre front-and-center to American reality

television.

Growing up, some of the only representations that I saw for myself was Mulan, an animated Chinese character, and I’m a Korean-American.

She hopes the

growing diversity in the industry will bring the music to more countries.

“Growing up, some

of the only representation that I saw for myself was Mulan, an animated Chinese

character, and I’m a Korean-American,” she quipped.

But since Korean

bands like

BLACKPINK and BTS went global, “K-pop has become such a safe space

for so many kids”.

She believes the

growing number of non-Korean idols within the industry is also good for her

adopted home.

“Korea is a rather homogenous country. So having all of

these foreign idols, I think it’s a really cool eye-opening opportunity for

Korea as well,” she said.

Read more Music

Jordan News