NEW YORK, United States —

It was a random morning in November, and Enheduanna was trending.

اضافة اعلان

Suddenly, the ancient

Mesopotamian priestess, who

had been dead for more than 4,000 years, was a hot topic online as word spread

that the first individually named author in human history was … a woman?

That may have been old news at the Morgan Library

& Museum, where Sidney Babcock, the longtime curator of ancient Near

Eastern antiquities, was about to offer a tour of its new exhibition “She Who

Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400–2000 BC”. Babcock was

thrilled by the attention, if not exactly surprised by the public’s surprise.

Ask people who the first author was, and they might

say Homer, or Herodotus. “People have no idea,” he said. “They simply don’t

believe it could be a woman” — and that she was writing more than a millennium

before either of them, in a strikingly personal voice.

Enheduanna’s work celebrates the gods and the power

of the

Akkadian empire, which ruled present-day Iraq from about 2350 BC to 2150

BC. But it also describes more sordid, earthly matters, including her abuse at

the hands of a corrupt priest — the first reference to sexual harassment in

world literature, the show argues.

“It’s the first time someone steps forward and uses

the first-person singular and gives an autobiography,” Babcock said. “And it’s

profound.”

Enheduanna has been known since 1927, when

archaeologists working at the ancient city of Ur excavated a stone disc bearing

her name (written with a starburst symbol) and image and identifying her as the

daughter of the king Sargon of Akkad, the wife of the moon god Nanna, and a

priestess.

In the decades that followed, her works — some 42

temple hymns and three stand-alone poems, including “The Exaltation of Inanna”

— were pieced together from more than 100 surviving copies made on clay

tablets.

Meanwhile, Enheduanna has been repeatedly

discovered, forgotten, and then discovered again by the broader culture. Last

fall, the “Exaltation” was added to

Columbia University’s famous first-year

Core Curriculum. And now there is the Morgan exhibition, which celebrates her

singularity while also embedding her in a deep history of women, literacy, and

power stretching back nearly to the ancient Mesopotamian origins of writing

itself.

The exhibition, on view until February 19, is also a

swan song for Babcock, who will retire next year after nearly three decades at

the Morgan. The idea began percolating about 25 years ago, he said, when he saw

Enheduanna’s name on a lapis lazuli cylinder seal belonging to one of her

scribes — one of five artifacts where her name is attested independently of

copies of her poetry.

He sees “She Who Wrote” — which assembles objects

from nine institutions around the world — as part of the Morgan’s long history

of exhibitions on female writers like Mary Shelley, Charlotte Brontë, and Emily

Dickinson.

It is also a tribute to a long chain of female

scholars, including his teacher, Edith Porada, the first curator of J. Pierpont

Morgan’s celebrated collection of more than 1,000 seals.

Porada, born in

Vienna, fled Europe in 1938 after

Kristallnacht. One of the few things she brought with her to New York was the

plate copy of her dissertation, complete with her drawings of seal impressions

from European collections, which she presented to Belle da Costa Greene, the

Morgan’s first director.

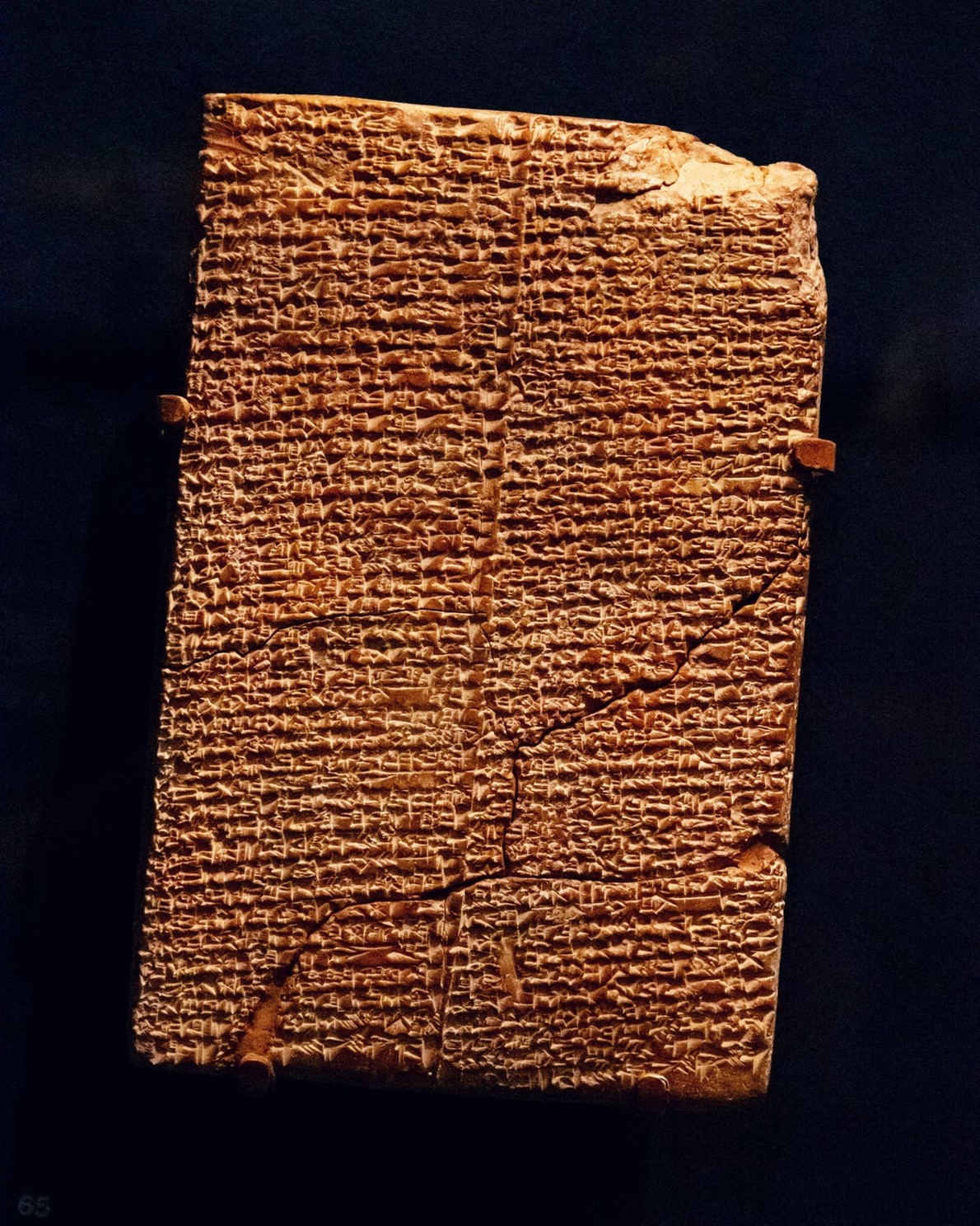

A clay tablet from ca. 1750 BC, inscribed with ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’, a poem attributed to Enheduanna, included in ‘She Who Wrote’, an exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, on November 7, 2022.

A clay tablet from ca. 1750 BC, inscribed with ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’, a poem attributed to Enheduanna, included in ‘She Who Wrote’, an exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, on November 7, 2022.

In ancient Mesopotamia, cylinder seals — often

carved with exquisitely detailed scenes — were used to roll the owner’s unique

stamp onto a document produced by scribes, attesting to its authenticity.

“For the first time”, Babcock said, “you have an

image that represents an individual connected with what the individual is

responsible for”.

Since 2010, about 100 of the Morgan seals have been

on permanent display in Greene’s jewel-box former office, in the opulent

original library building. But for years they were stored in a gym-style steel

locker in a basement, where Porada would hold a weekly seminar.

“We would sit down, and out of her purse would come

a little change purse with a key inside,” Babcock recalled. “She would open

another locker, and inside a Sucrets tin was another key. Then we would gasp —

out of the locker would come this legendary collection.”

Entering the gallery, Babcock (who curated the show

with Erhan Tamur, a curatorial fellow at the Metropolitan Museum) paused in

front of a tiny alabaster sculpture of a seated woman, from around 2000BC. She

is wearing the same flounce garment seen in the image of Enheduanna on the disk

found in 1927 and has the same aquiline features. A cuneiform tablet rests on

her lap, as if she is ready to write.

Is it Enheduanna?

“My colleagues won’t let me go that far,” Babcock

said. But the figure “certainly represents the idea of what she meant — women

and literacy, over successive generations.”

Many of the sculptures on display, the show argues,

depict actual individuals, not generic women. “This was the beginning of

portraiture,” Babcock said. And over the course of a nearly two-hour tour, he

repeatedly broke off his narrative to marvel at the beauty of this or that

figure, as if spotting a fashionable friend across the room.

At the center of the gallery is an item that would

spark a paparazzi frenzy at any

Met Gala: a spectacular funerary ensemble from

the tomb of Puabi, a Sumerian queen who lived around 2500BC, complete with an

elaborate beaten-gold headdress and cascading strands of semiprecious stones.

But equally remarkable, for Babcock, is the gold

garment pin displayed nearby, which would have held amulets and cylinder seals,

like the one carved from lapis lazuli found on Puabi’s body.

Enheduanna lived three centuries after Puabi,

following the ascendance of the Akkadians, who united speakers of the Sumerian

and Akkadian languages. Compared with Puabi’s ensemble, her surviving remnants

might seem drab.

But Enheduanna’s glory lies in her words, some of

which address startlingly contemporary concerns.

Some scholars have questioned whether Enheduanna

wrote the poems attributed to her. Even if she was a real person, they argue,

the works — written in Sumerian, and known only from copies made hundreds of

years after her lifetime — may have been written later and attributed to her,

as a way of bolstering the legacy of Sargon the king.

But whether Enheduanna was an actual author or a

symbol of one, she was hardly alone. The recent anthology “Women’s Writing of

Ancient Mesopotamia” gathers nearly 100 hymns, poems, letters, inscriptions,

and other texts by female authors.

In one passage of “Exaltation” — unique in all of

Mesopotamian literature, Babcock said — Enheduanna describes herself as “giving

birth” to the poem. “That which I have sung to you at midnight”, she wrote,

“may it be repeated at noon”.

And repeated it was. While the Akkadian empire

collapsed in 2137BC, Enheduanna’s poems continued to be copied for centuries,

as part of the standard training of scribes.

By about 500BC,

Enheduanna was “completely forgotten”, Babcock said. But until February, she

and her fellow women of Mesopotamia will command the room at the Morgan.

“Even the backs are so exquisite,” Babcock said, taking a

last look at the stone figures before returning to his office. “It can be hard

to leave.”

Read more Trending

Jordan News