Visitors to the new

Bob Dylan Center here

will soon get, at the tap of a finger, what generations of the most avid

Dylanologists have only dreamed of: a step-by-step, word-by-word map of how

Dylan wrote a song.

اضافة اعلان

In a room filled with artifacts a digital display

lets visitors sift through 10 of the 17 known drafts of Dylan’s cryptic 1983 song

“Jokerman”. The screen highlights typed and handwritten changes Dylan made

throughout the manuscripts, showing, for example, how the line “You a son of

the angels/You a man of the clouds” in the song’s earliest iteration was

tweaked, little by little, to end up as “You’re a man of the mountains, you can

walk on the clouds”.

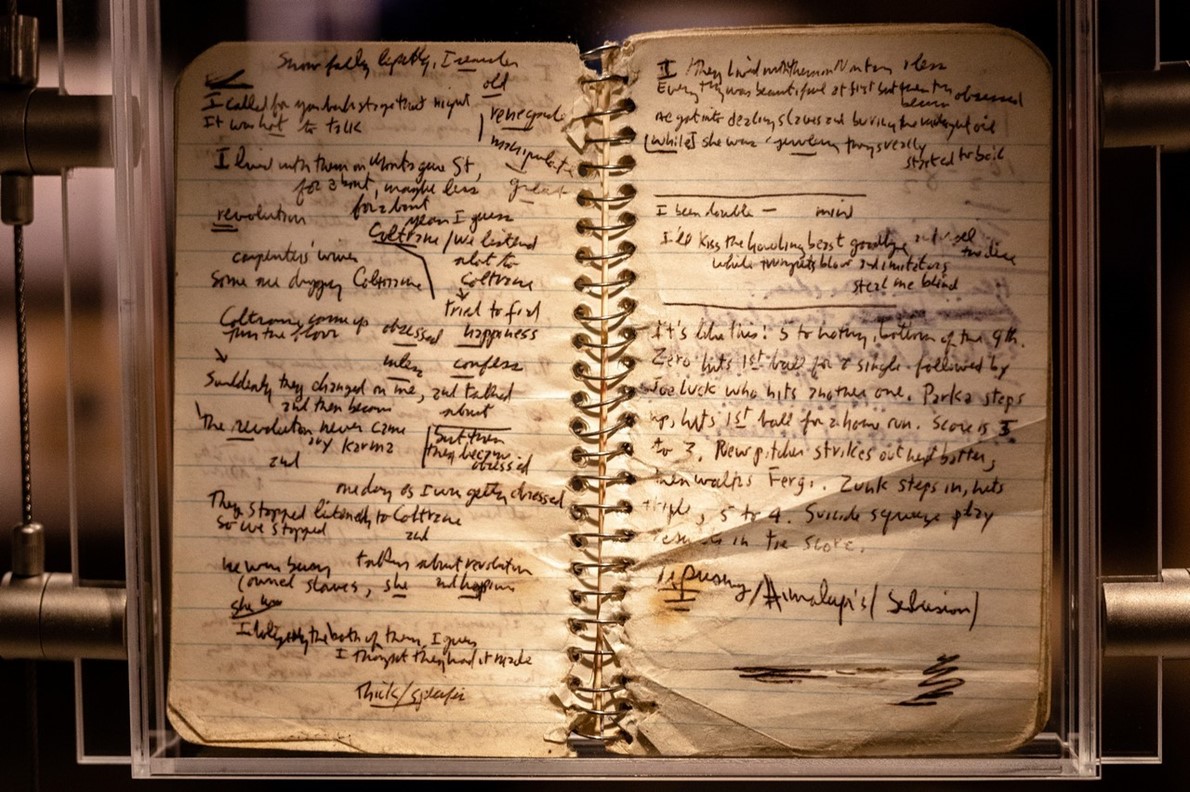

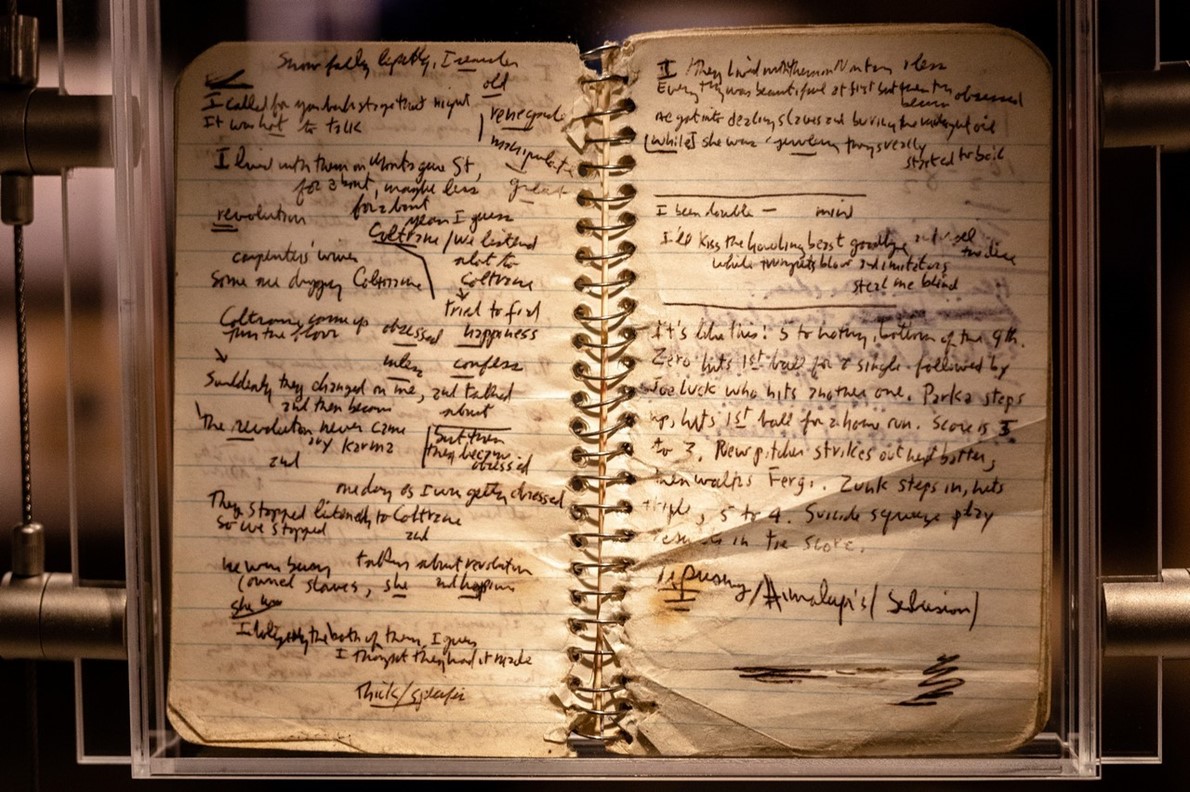

One of three notebooks containing original handwritten lyrics used on the Bob Dylan album ‘Blood on the Tracks’ on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma., April 30, 2022.

One of three notebooks containing original handwritten lyrics used on the Bob Dylan album ‘Blood on the Tracks’ on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma., April 30, 2022.

The “Jokerman” exhibit is one instance of how the

organizers of the $10 million Dylan Center — which opens Tuesday, after a long

weekend of inaugural events featuring Elvis Costello, Patti Smith and Mavis

Staples — have tried to bring Dylan’s paper-heavy archives to life and entice

newcomers and experts alike.

It also points to the center’s larger aim of using

Dylan’s vast archive, with documents and artifacts from nearly his entire career,

to illuminate the creative process itself. In addition to exhibits focused on

Dylan’s work, the two-floor, 29,000-square-foot facility will have a rotating

gallery featuring the work of other creators. First up is Jerry Schatzberg, the

filmmaker and photographer who shot the cover of Dylan’s 1966 album “Blonde on

Blonde”.

“We’re really hoping that visitors walk away with a

sense that they can tap into their own creative instincts, their own impulse

for artistic expression, in whatever medium that might be,” Steven Jenkins, the

center’s director, said on a recent tour.

The Dylan Center, located at one end of a

century-old brick industrial building in downtown Tulsa — the Woody Guthrie

Center, devoted to Dylan’s early hero, is at the other — is the museum-like

space founded to display items from the Bob Dylan Archive, which was acquired

in 2016 by the

George Kaiser Family Foundation and the University of Tulsa for

around $20 million. (The Kaiser foundation later bought out the university’s

share.)

The full archive, with about 100,000 items, is

available only to credentialed researchers. It includes huge amounts of

paperwork as well as films, recordings, photographs, books, musical instruments

and curiosities like matchbooks on which Dylan scrawled a few words. (For fire

safety reasons, the matchbooks are kept elsewhere.) Among the many highlights:

a newly discovered film soundtrack from 1961 and four typewritten drafts of

“Tarantula”, the book of disjointed prose poetry that Dylan wrote in the

mid-60s.

In characteristic fashion, Dylan — fully active at

80, with a tour on the road and a new book coming out in the fall — has

stubbornly avoided engaging with attempts to examine his own work, and had no

involvement in the center that bears his name, aside from contributing one of

his ironwork gates for the entryway. (His business office in

New York, however,

has been closely involved.) When he performed in Tulsa last month, at a theater

just a few blocks away, the Nobel laureate made no acknowledgment of the institution

in his honor about to open just down the street.

The challenge for

the Dylan Center is to make the archive understandable to lay audiences while

also drawing on its depths to please the fussiest Dylan experts — the types who

may be well-versed on minutiae like the murky provenance of the red spiral

notebook Dylan used for “Blood on the Tracks,” which is at the Morgan Library

& Museum in New York.

One step was to not

call the new facility a museum at all, but rather a “center” that would

encourage debate and welcome multiple perspectives.

A bag of fan mail directed to Bob Dylan in 1966, on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma., April 30, 2022.

A bag of fan mail directed to Bob Dylan in 1966, on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma., April 30, 2022.

“I’m more

interested in this as a living archive than as a museum,” said Alan Maskin of

Olson Kundig, the architecture and design firm behind the Dylan Center. “Museum

implies a voice that everyone accepts as truth.”

Some items, like a

duffel bag of fan mail from 1966, deliver an immediate emotional impact. In

letters from the beginning of the year, fans plead for photos and autographs as

if Dylan were any pop idol. Get-well cards poured in after his motorcycle accident

that July. A November letter from a soldier in Vietnam describes a young man

hearing “Blowin’ in the Wind” on the radio while mourning three fallen friends

in a “blood drenched country”.

Yet Dylan never

read this correspondence. According to Mark A. Davidson, the curator of the

Dylan Archive, the bag had apparently sat untouched for years, and when

archivists received it, none of the mail had been opened.

The center, and the

archive, are already evolving. Exhibits like the jukebox will rotate among

guest curators. And the Dylan Archive has been steadily expanding. In 2016, it

purchased the original tambourine of Bruce Langhorne, who inspired Dylan’s song

“Mr. Tambourine Man”. More recently it has acquired extensive collections from

Mitch Blank in New York and Bill Pagel, who owns two of Dylan’s childhood homes

in Minnesota, as well as books and LPs from Harry Smith, the filmmaker and

polymath known for compiling the seminal “Anthology of American Folk Music”

(1952).

But market values

for

music archives have soared, in part as a result of Dylan’s own deal.

Davidson said that many well-known musicians have offered to sell their

collections, saying: “We want Bob Dylan money.” Jenkins, the center’s director,

said that while the Kaiser foundation covered about half of its $10 million

opening cost — the rest was raised from donors — the institution will seek to

establish enough revenue sources to become financially “self-sustaining”.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News