Six days, eight dives, and breathtaking beauty off the coast of Honduras

New York Times

last updated: Feb 15,2022

Scuba divers are much like children, I imagine, to

dive-resort owners: They are almost always wonderful to have, but at night,

it’s best if they are safely in their beds.اضافة اعلان

This thought popped into my head at the end of a night dive, off the southern shore of the Honduran island of Roatán in December. As the sun set, four of us had waded into the dark waters that lay only yards from the Reef House Resort, and swam down the side of a steep underwater cliff, holding flashlights to illuminate trumpet fish, lobsters, brain coral, sea fans, and the other marine life that call this part of the nearly 1,127km Mesoamerican Reef home. Night dives were new to me: The inky darkness was exhilarating, mysterious, alive, and more than a little frightening.

(Photo: NYTimes)

After 45 minutes of underwater wonderment, I safely ascended and surfaced while Aaren, my travel partner, and our new scuba buddies, Will and Kris, stayed just below, taking one last photograph. But instead of emerging to silence and milky white stars, I saw a figure with a flashlight standing on the nearby jetty, shouting.

“Follow my light! Do you hear my voice? Swim to me,” called Davey Byrne, a co-owner of the Reef House, our home for three nights over the Christmas holiday.

Surprised, I responded by blurting out the first thing in my head: “It’s OK! We were just looking at two cuttle fish!”

Davey laughed and said no problem, he simply wanted to make sure we were all right. The bar, and dinner, were waiting whenever we got out of the water.

Eating, diving, sleeping, on repeat

About 56km off the northern coast of mainland Honduras, Roatán is the largest of the Bay Islands, an archipelago encircled by some of the prettiest and most accessible coral reefs anywhere in the world. Deciding not to cancel this international trip — our first since the pandemic began — was a gut buster, as it was for many who had holiday travel plans this year.

(Photo: NYTimes)

The Bay Islands lie along the southern end of the Mesoamerican Reef, one of the largest barrier reefs in the world (Australia’s Great Barrier Reef comes first in this category) — it touches Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize, as well as Honduras. It’s a vibrant, diverse marine ecosystem, with around 65 coral species, more than 500 types of fish and almost countless other examples of marine life like sea turtles and sponges.

It delivered. We made our base at the rustic 10-room Reef House, on a cay a brief boat ride from the village of Oakridge, and spent our days eating, diving, sleeping, on repeat. Four days, eight dives, one snorkel, countless creatures, breathtaking beauty.

None of the dive sites were more than a 10-minute ride from the resort, on the dive boat docked at the Reef House. Swimming down vertical reef walls and through coral canyons, we spotted green moray eels, nurse sharks, toadfish, puffer fish, schools of blue chromis, and invasive lionfish. Our dive master, David, skewered many of the last in front of us to our horrified delight. The colors, textures, and shapes of the corals and sea fans ranged from the reds and greens of Christmas to a Southwest landscape of cactus-like corals in shades of sand and lavender.

(Photo: NYTimes)

Never were there more than four divers on an outing, excluding our dive master, nor another boat at the mooring.

A fragile economy

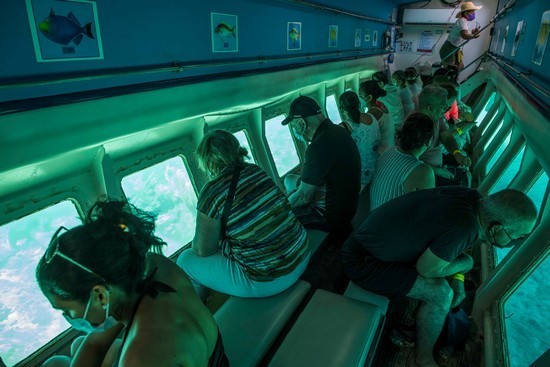

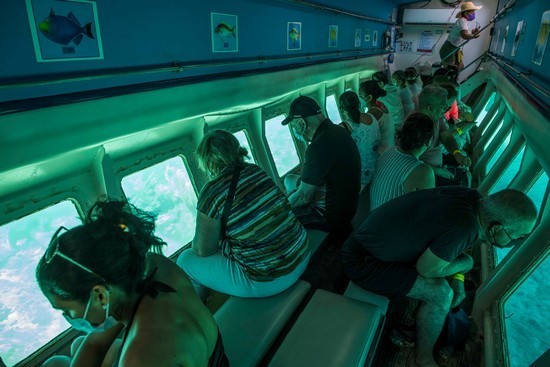

This lack of company was glorious, although not so much to the Reef House or the island’s greater economy. The Bay Islands had a pre-pandemic economy almost entirely based on tourism, an evolution that came after the island’s commercial fishing collapsed. Tourism started when the scuba community and “the hardy” found the archipelago in the 1970s, but with the arrival of major cruise lines in the 2000s, its popularity exploded, with three ships or more arriving each day, three or more days a week in the high season before the pandemic.

In 2005, several local dive operators established the Roatán Marine Park, now a 22-employee nonprofit that aims to conserve the reef with coral restoration efforts, coastline patrolling, research and community engagement and education. It’s part of the Bay Islands National Marine Park, a marine sanctuary declared by the government of Honduras in 2010 to protect the coast and marine life around the islands.

“From taxi drivers to scuba divers, the reef is important to everyone,” said Gabriela Ochoa, a program manager for the Roatán Marine Park, of the local population. “I think at least one person in every household relies on the tourism sector. Basically, this island runs on tourism.”

(Photo: NYTimes)

In March 2020, the Bay Islands abruptly shut to cruise ships and both international and domestic flights for more than six months (leaving some travelers stranded). For the early part of the pandemic, the local population was under strict curfew. No visiting the beach. Twice-monthly access to food stores. GoFundMe campaigns as well as soup kitchens and food pantries were created to help residents.

Roatán has yet to see tourist numbers bounce back, with flight arrivals between January and September 2021 numbering around 270,000, around two-thirds of that reported for all of 2019, according to the Honduran Institute of Tourism. Cruise ship passenger numbers were even lower: Dropping from 1.4 million in all of 2019 to 180,000 from July to November 2021.

A fragile ecosystem

Aaren spotted the differences first. On the western side of the island, the corals appeared to be smaller, and carried more algae. The underwater scene still delighted — when I was in the water, two tuna swam by, a suspicious barracuda checked me out, three remora, sometimes known as suckerfish, may have wanted to stick their heads on my head and that sea turtle grazing on sea grass will never be forgotten — but it was clear, even to a nonexpert, that there were fewer fish, fewer corals, less life.

I learned the reasons later, from Ian Drysdale, the Honduras coordinator of the Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative. For the past 14 years, this nonprofit has brought together the governments of Honduras, Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala, along with 80 partner organizations, to analyze the health of the Mesoamerican Reef. Every two years, the nonprofit issues a report card that assesses the main indicators of reef health: the percentage of live coral cover and that of macroalgae on the 286 monitored sites, as well as the abundance of herbivorous fish (like parrotfish), and grouper and other commercially important species.

(Photo: NYTimes)

The reef is having a very hard time. For years, this part of the island — and its corals — took on most of the stress of the tourist population. Then the lack of tourists during the pandemic led to food insecurity among the Bay Islanders and poaching increased by 150 percent, Ochoa said.

The community of Roatán, for better or for worse, relies on its reef, and now certified divers can give back: Researchers have determined that a topical application of marine epoxy and antibiotics can hamper the spread of stony coral tissue loss disease among some species of hard corals.

Now they are looking to train certified divers, including environmentally minded tourists, to apply antibiotics, with a large syringe, into pillar, brain and other stony corals. The project in Honduras is spearheaded by the Roatán Marine Park; working with local dive shops, the nonprofit has organized orientation and training sessions for certified divers to help the reefs, either with syringes, collecting data, or tagging corals for future evaluation.

Important ties

During our dives in this beautiful ecosystem, the coronavirus and its related worries were finally far from my mind. The exposure to this marine community, however, led me to ponder how important relationships are, both under the sea and above the water, on the shores of Roatán and beyond.

Symbiotic relationships are common in the natural world. On the world’s coral reefs, parrotfish feed on algae, keeping the plants in check, allowing corals to grow (mutualistic is the term biologists use), while those remora fish prefer to hitch a ride on sharks, not snorkelers (that’s a commensalistic relationship).

(Photo: NYTimes)

The pandemic laid bare the relationship that many destinations around the world have with tourists. It’s a relationship that is at times both mutualistic and commensalistic, although many would argue that it is, overall, parasitic. Now, with the reflection gained from the pandemic travel lull, we have a chance, perhaps an obligation, to rethink our own relationships with the places we visit and rebuild them stronger. That might mean not only opening our wallets, but turning to smart organizations like the Roatán Marine Park for guidance and education, and even, perhaps, wielding a medical syringe as we explore a coral reef.

So, instead of banning visitors outright to environmentally sensitive places, said Drysdale of Healthy Reefs, a portion of travel revenue could be devoted to reducing their impact, such as modernizing wastewater treatment plants or improving plastic recycling.

As for Roatán itself, Drysdale said, he hopes sustainable travelers will come, and become acquainted with the island’s beauty, and then he paraphrased some words from the famed ecologist Baba Dioum: “You won’t protect what you don’t know, and you protect what you love.”

Read more Travel

This thought popped into my head at the end of a night dive, off the southern shore of the Honduran island of Roatán in December. As the sun set, four of us had waded into the dark waters that lay only yards from the Reef House Resort, and swam down the side of a steep underwater cliff, holding flashlights to illuminate trumpet fish, lobsters, brain coral, sea fans, and the other marine life that call this part of the nearly 1,127km Mesoamerican Reef home. Night dives were new to me: The inky darkness was exhilarating, mysterious, alive, and more than a little frightening.

(Photo: NYTimes)

After 45 minutes of underwater wonderment, I safely ascended and surfaced while Aaren, my travel partner, and our new scuba buddies, Will and Kris, stayed just below, taking one last photograph. But instead of emerging to silence and milky white stars, I saw a figure with a flashlight standing on the nearby jetty, shouting.

“Follow my light! Do you hear my voice? Swim to me,” called Davey Byrne, a co-owner of the Reef House, our home for three nights over the Christmas holiday.

Surprised, I responded by blurting out the first thing in my head: “It’s OK! We were just looking at two cuttle fish!”

Davey laughed and said no problem, he simply wanted to make sure we were all right. The bar, and dinner, were waiting whenever we got out of the water.

Eating, diving, sleeping, on repeat

About 56km off the northern coast of mainland Honduras, Roatán is the largest of the Bay Islands, an archipelago encircled by some of the prettiest and most accessible coral reefs anywhere in the world. Deciding not to cancel this international trip — our first since the pandemic began — was a gut buster, as it was for many who had holiday travel plans this year.

(Photo: NYTimes)

The Bay Islands lie along the southern end of the Mesoamerican Reef, one of the largest barrier reefs in the world (Australia’s Great Barrier Reef comes first in this category) — it touches Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize, as well as Honduras. It’s a vibrant, diverse marine ecosystem, with around 65 coral species, more than 500 types of fish and almost countless other examples of marine life like sea turtles and sponges.

It delivered. We made our base at the rustic 10-room Reef House, on a cay a brief boat ride from the village of Oakridge, and spent our days eating, diving, sleeping, on repeat. Four days, eight dives, one snorkel, countless creatures, breathtaking beauty.

None of the dive sites were more than a 10-minute ride from the resort, on the dive boat docked at the Reef House. Swimming down vertical reef walls and through coral canyons, we spotted green moray eels, nurse sharks, toadfish, puffer fish, schools of blue chromis, and invasive lionfish. Our dive master, David, skewered many of the last in front of us to our horrified delight. The colors, textures, and shapes of the corals and sea fans ranged from the reds and greens of Christmas to a Southwest landscape of cactus-like corals in shades of sand and lavender.

(Photo: NYTimes)

Never were there more than four divers on an outing, excluding our dive master, nor another boat at the mooring.

A fragile economy

This lack of company was glorious, although not so much to the Reef House or the island’s greater economy. The Bay Islands had a pre-pandemic economy almost entirely based on tourism, an evolution that came after the island’s commercial fishing collapsed. Tourism started when the scuba community and “the hardy” found the archipelago in the 1970s, but with the arrival of major cruise lines in the 2000s, its popularity exploded, with three ships or more arriving each day, three or more days a week in the high season before the pandemic.

In 2005, several local dive operators established the Roatán Marine Park, now a 22-employee nonprofit that aims to conserve the reef with coral restoration efforts, coastline patrolling, research and community engagement and education. It’s part of the Bay Islands National Marine Park, a marine sanctuary declared by the government of Honduras in 2010 to protect the coast and marine life around the islands.

“From taxi drivers to scuba divers, the reef is important to everyone,” said Gabriela Ochoa, a program manager for the Roatán Marine Park, of the local population. “I think at least one person in every household relies on the tourism sector. Basically, this island runs on tourism.”

(Photo: NYTimes)

In March 2020, the Bay Islands abruptly shut to cruise ships and both international and domestic flights for more than six months (leaving some travelers stranded). For the early part of the pandemic, the local population was under strict curfew. No visiting the beach. Twice-monthly access to food stores. GoFundMe campaigns as well as soup kitchens and food pantries were created to help residents.

Roatán has yet to see tourist numbers bounce back, with flight arrivals between January and September 2021 numbering around 270,000, around two-thirds of that reported for all of 2019, according to the Honduran Institute of Tourism. Cruise ship passenger numbers were even lower: Dropping from 1.4 million in all of 2019 to 180,000 from July to November 2021.

A fragile ecosystem

Aaren spotted the differences first. On the western side of the island, the corals appeared to be smaller, and carried more algae. The underwater scene still delighted — when I was in the water, two tuna swam by, a suspicious barracuda checked me out, three remora, sometimes known as suckerfish, may have wanted to stick their heads on my head and that sea turtle grazing on sea grass will never be forgotten — but it was clear, even to a nonexpert, that there were fewer fish, fewer corals, less life.

I learned the reasons later, from Ian Drysdale, the Honduras coordinator of the Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative. For the past 14 years, this nonprofit has brought together the governments of Honduras, Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala, along with 80 partner organizations, to analyze the health of the Mesoamerican Reef. Every two years, the nonprofit issues a report card that assesses the main indicators of reef health: the percentage of live coral cover and that of macroalgae on the 286 monitored sites, as well as the abundance of herbivorous fish (like parrotfish), and grouper and other commercially important species.

(Photo: NYTimes)

The reef is having a very hard time. For years, this part of the island — and its corals — took on most of the stress of the tourist population. Then the lack of tourists during the pandemic led to food insecurity among the Bay Islanders and poaching increased by 150 percent, Ochoa said.

The community of Roatán, for better or for worse, relies on its reef, and now certified divers can give back: Researchers have determined that a topical application of marine epoxy and antibiotics can hamper the spread of stony coral tissue loss disease among some species of hard corals.

Now they are looking to train certified divers, including environmentally minded tourists, to apply antibiotics, with a large syringe, into pillar, brain and other stony corals. The project in Honduras is spearheaded by the Roatán Marine Park; working with local dive shops, the nonprofit has organized orientation and training sessions for certified divers to help the reefs, either with syringes, collecting data, or tagging corals for future evaluation.

Important ties

During our dives in this beautiful ecosystem, the coronavirus and its related worries were finally far from my mind. The exposure to this marine community, however, led me to ponder how important relationships are, both under the sea and above the water, on the shores of Roatán and beyond.

Symbiotic relationships are common in the natural world. On the world’s coral reefs, parrotfish feed on algae, keeping the plants in check, allowing corals to grow (mutualistic is the term biologists use), while those remora fish prefer to hitch a ride on sharks, not snorkelers (that’s a commensalistic relationship).

(Photo: NYTimes)

The pandemic laid bare the relationship that many destinations around the world have with tourists. It’s a relationship that is at times both mutualistic and commensalistic, although many would argue that it is, overall, parasitic. Now, with the reflection gained from the pandemic travel lull, we have a chance, perhaps an obligation, to rethink our own relationships with the places we visit and rebuild them stronger. That might mean not only opening our wallets, but turning to smart organizations like the Roatán Marine Park for guidance and education, and even, perhaps, wielding a medical syringe as we explore a coral reef.

So, instead of banning visitors outright to environmentally sensitive places, said Drysdale of Healthy Reefs, a portion of travel revenue could be devoted to reducing their impact, such as modernizing wastewater treatment plants or improving plastic recycling.

As for Roatán itself, Drysdale said, he hopes sustainable travelers will come, and become acquainted with the island’s beauty, and then he paraphrased some words from the famed ecologist Baba Dioum: “You won’t protect what you don’t know, and you protect what you love.”

Read more Travel