Brain implant allows fully paralyzed patient to communicate

New York Times

last updated: Apr 05,2022

In 2020, Ujwal Chaudhary, a biomedical

engineer then at the University of Tübingen and the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, watched his computer with amazement as an

experiment that he had spent years on revealed itself. A 34-year-old paralyzed

man lay on his back in the laboratory, his head connected by a cable to a

computer. A synthetic voice pronounced letters in German: “E, A, D … ”اضافة اعلان

The patient had been diagnosed a few years earlier with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which leads to the progressive degeneration of brain cells involved in motion. The man had lost the ability to move even his eyeballs and was entirely unable to communicate; in medical terms, he was in a completely locked-in state.

Or so it seemed. Through Chaudhary’s experiment, the man had learned to select — not directly with his eyes but by imagining his eyes moving — individual letters from the steady stream that the computer spoke aloud. Letter by painstaking letter, one every minute or so, he formulated words and sentences.

“Wegen essen da wird ich erst mal des curry mit kartoffeln haben und dann bologna und dann gefuellte und dann kartoffeln suppe,” he wrote at one point: “For food I want to have curry with potato then bologna and potato soup.”

Chaudhary and his colleagues were dumbstruck. “I myself could not believe that this is possible,” recalled Chaudhary, who is now managing director at ALS Voice gGmbH, a neurobiotechnology company based in Germany, and who no longer works with the patient.

The study, published recently in Nature Communications, provides the first example of a patient in a fully locked-in state communicating at length with the outside world, said Niels Birbaumer, the leader of the study and a former neuroscientist at the University of Tübingen who is now retired.

Chaudhary and Birbaumer conducted two similar experiments in 2017 and 2019 on patients who were completely locked-in and reported that they were able to communicate. Both studies were retracted after an investigation by the German Research Foundation concluded that the researchers had only partially recorded the examinations of their patients on video, had not appropriately shown details of their analyses and had made false statements.

The German Research Foundation, finding that Birbaumer committed scientific misconduct, imposed some of its most severe sanctions, including a five-year ban on submitting proposals and serving as a reviewer for the foundation.

The agency found that Chaudhary had also committed scientific misconduct and imposed the same sanctions for a three-year period. Both he and Birbaumer were asked to retract their two papers, and they declined.

The investigation came after a whistleblower, Martin Spüler, a researcher, raised concerns about the two scientists in 2018.

Birbaumer stood by the conclusions and has taken legal action against the German Research Foundation. The results of the lawsuit are expected to be published in the upcoming week, said Marco Finetti, a spokesperson for the German Research Foundation. Chaudhary said his lawyers expected to win the case.

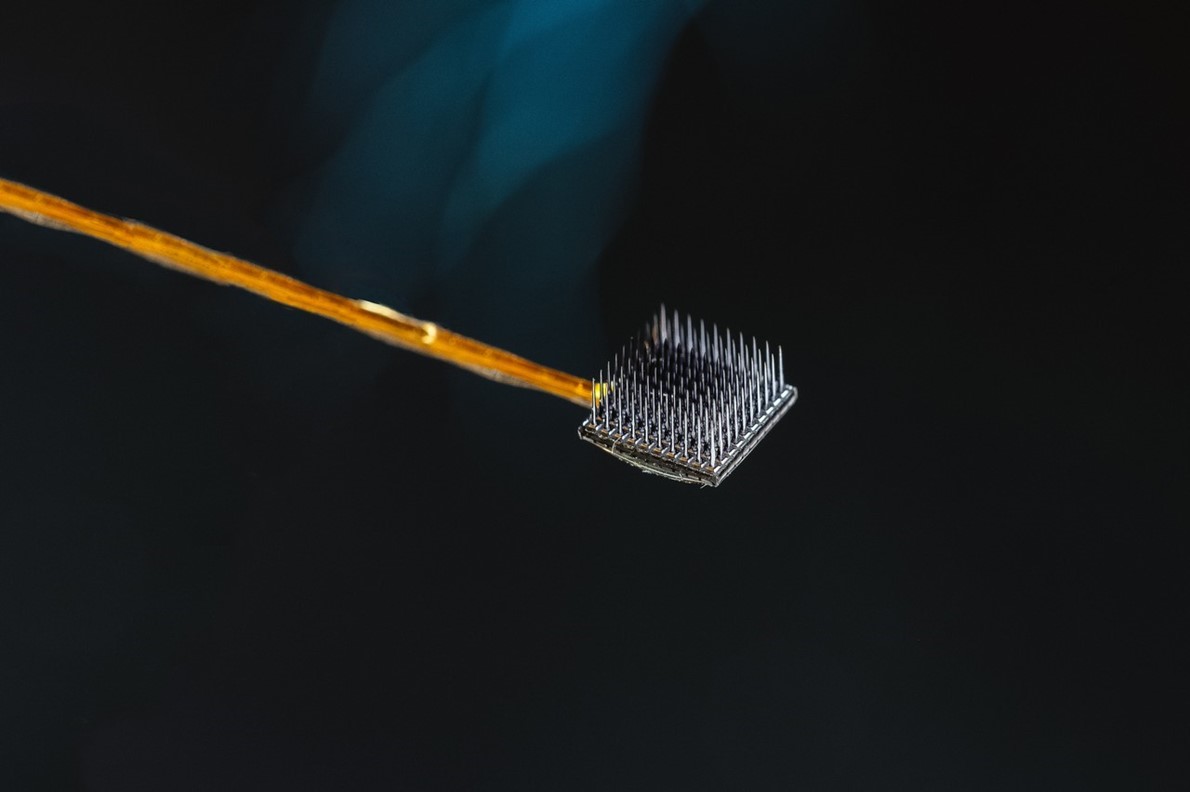

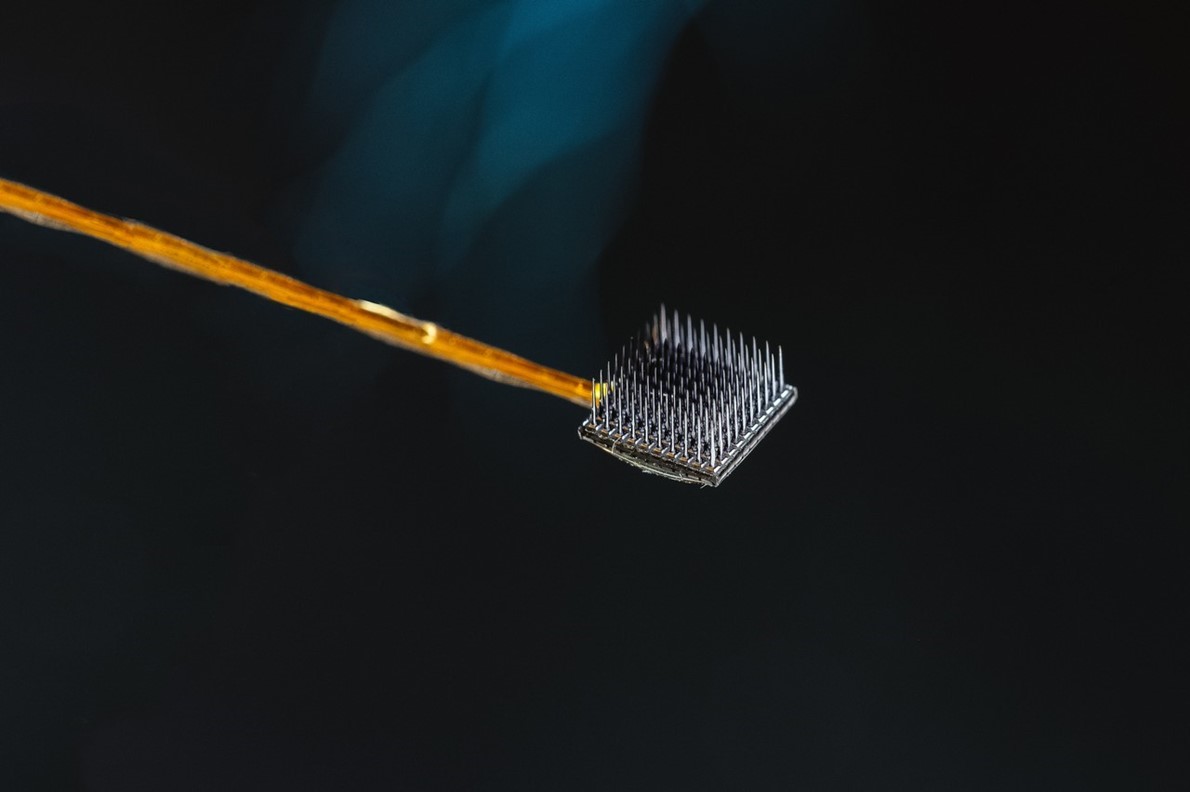

One of two microelectrode arrays, each 3.2 mm square, that were inserted into the surface of a patient’s motor cortex — the part of the brain responsible for movement.

The German Research Foundation had no knowledge of the publication of the current study and will investigate it in the coming months, Finetti said. In an email, a representative for Nature Communications who asked not to be named declined to comment on the details of how the study was vetted but expressed confidence with the process. “We have rigorous policies to safeguard the integrity of the research we publish, including to ensure that research has been conducted to a high ethical standard and is reported transparently,” the representative said.

“I would say it is a solid study,” said Natalie Mrachacz-Kersting, a brain-computer interface researcher at the University of Freiburg in Germany. She was not involved in the study and was aware of the previously retracted papers.

But Brendan Allison, researcher at the University of California San Diego, expressed reservations. “This work, like other work by Birbaumer, should be taken with a massive mountain of salt given his history,” Allison said. He noted that in a paper published in 2017, his own team had described being able to communicate with completely locked-in patients with basic “yes” or “no” answers.

The results hold potential promise for patients in similarly unresponsive situations, including minimally conscious and comatose states, as well as the rising number of people diagnosed with ALS worldwide every year. That number is projected to reach 300,000 by 2040.

“It’s a game-changer,” said Steven Laureys, a neurologist and researcher who leads the Coma Science Group at the University of Liège in Belgium and was not involved in the study. The technology could have ethical ramifications in discussions surrounding physician-assisted suicide for patients in locked-in or vegetative states, he added; “it’s really great to see this moving forward, giving patients a voice” in their own decisions.

Myriad methods have been used to communicate with unresponsive patients. Some involve basic pen-and-paper methods devised by family relatives. In others, a caregiver points to or speaks the names of items and looks for microresponses — blinks or finger twitches from the patient.

In recent years, a new method has taken center stage: brain-computer interface technologies, which aim to translate a person’s brain signals into commands. Research institutes, private companies, and entrepreneurial billionaires like Elon Musk have invested heavily in the technology.

The results have been mixed but compelling: patients moving prosthetic limbs using only their thoughts, and those with strokes, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions communicating once again with loved ones.

What scientists have been unable to do until now, however, is communicate extensively with people like the man in the new study who displayed no movements whatsoever.

In 2017, before becoming totally locked-in, the patient had used eye movements to communicate with his family. Anticipating that he would soon lose even this ability, the family asked for an alternative communication system and approached Chaudhary and Birbaumer, a pioneer in the field of brain-computer interface technology, both of whom worked nearby.

With the man’s approval, Dr. Jens Lehmberg, a neurosurgeon and an author on the study, implanted two tiny electrodes in regions of the man’s brain that are involved in controlling movement. Then, for two months, the man was asked to imagine moving his hands, arms and tongue to see if these would generate a clear brain signal. But the effort yielded nothing reliable.

Birbaumer then suggested using auditory neurofeedback, an unusual technique by which patients are trained to actively manipulate their own brain activity. The man was first presented with a note — high or low, corresponding to yes or no. This was his “target tone” — the note he had to match.

He was then played a second note, which mapped onto brain activity that the implanted electrodes had detected. By concentrating — and imagining moving his eyes, to effectively dial his brain activity up or down — he was able to change the pitch of the second tone to match the first. As he did so, he gained real-time feedback of how the note changed, allowing him to heighten the pitch when he wanted to say yes or lower it for no.

This approach saw immediate results. On the man’s first day trying, he was able to alter the second tone. Twelve days later, he succeeded in matching the second to the first.

“That was when everything became consistent, and he could reproduce those patterns,” said Jonas Zimmermann, a neuroscientist at theWyss Center and an author on the study. When the patient was asked what he was imagining to alter his own brain activity, he replied, “Eye movement.”

Over the next year, the man applied this skill to generate words and sentences. The scientists borrowed a communication strategy that the patient had used with his family when he could still move his eyes.

At this stage, the technology is far too complex for patients and families to operate. Making it more user-friendly and speeding up communication will be crucial, Chaudhary said. Until then, he said, a patient’s relatives will probably be satisfied.

“You have two options: no communication or communication at 1 character per minute,” he said. “What do you choose?”

Perhaps the biggest concern is time. Three years have passed since the implants were first inserted in the patient’s brain. Since then, his answers have become significantly slower, less reliable and often impossible to discern, said Zimmermann, who is now caring for the patient at the Wyss Center.

The cause of this decline is unclear, but Zimmermann thought it probably stemmed from technical issues. For instance, the electrodes are nearing the end of their life expectancy. Replacing them now, however, would be unwise. “It’s a risky procedure,” he said. “All of a sudden, you’re exposed to new kinds of bacteria in the hospital.”

Zimmermann and others at the Wyss Center are developing wireless microelectrodes that are safer to use. The team is also exploring other noninvasive techniques that have proved fruitful in previous studies on patients who are not locked-in. “As much as we want to help people, I think it’s also very dangerous to create false hope,” Zimmermann said.

Read more Health

Jordan News

The patient had been diagnosed a few years earlier with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which leads to the progressive degeneration of brain cells involved in motion. The man had lost the ability to move even his eyeballs and was entirely unable to communicate; in medical terms, he was in a completely locked-in state.

Or so it seemed. Through Chaudhary’s experiment, the man had learned to select — not directly with his eyes but by imagining his eyes moving — individual letters from the steady stream that the computer spoke aloud. Letter by painstaking letter, one every minute or so, he formulated words and sentences.

“Wegen essen da wird ich erst mal des curry mit kartoffeln haben und dann bologna und dann gefuellte und dann kartoffeln suppe,” he wrote at one point: “For food I want to have curry with potato then bologna and potato soup.”

Chaudhary and his colleagues were dumbstruck. “I myself could not believe that this is possible,” recalled Chaudhary, who is now managing director at ALS Voice gGmbH, a neurobiotechnology company based in Germany, and who no longer works with the patient.

The study, published recently in Nature Communications, provides the first example of a patient in a fully locked-in state communicating at length with the outside world, said Niels Birbaumer, the leader of the study and a former neuroscientist at the University of Tübingen who is now retired.

Chaudhary and Birbaumer conducted two similar experiments in 2017 and 2019 on patients who were completely locked-in and reported that they were able to communicate. Both studies were retracted after an investigation by the German Research Foundation concluded that the researchers had only partially recorded the examinations of their patients on video, had not appropriately shown details of their analyses and had made false statements.

The German Research Foundation, finding that Birbaumer committed scientific misconduct, imposed some of its most severe sanctions, including a five-year ban on submitting proposals and serving as a reviewer for the foundation.

The agency found that Chaudhary had also committed scientific misconduct and imposed the same sanctions for a three-year period. Both he and Birbaumer were asked to retract their two papers, and they declined.

The investigation came after a whistleblower, Martin Spüler, a researcher, raised concerns about the two scientists in 2018.

Birbaumer stood by the conclusions and has taken legal action against the German Research Foundation. The results of the lawsuit are expected to be published in the upcoming week, said Marco Finetti, a spokesperson for the German Research Foundation. Chaudhary said his lawyers expected to win the case.

One of two microelectrode arrays, each 3.2 mm square, that were inserted into the surface of a patient’s motor cortex — the part of the brain responsible for movement.

The German Research Foundation had no knowledge of the publication of the current study and will investigate it in the coming months, Finetti said. In an email, a representative for Nature Communications who asked not to be named declined to comment on the details of how the study was vetted but expressed confidence with the process. “We have rigorous policies to safeguard the integrity of the research we publish, including to ensure that research has been conducted to a high ethical standard and is reported transparently,” the representative said.

“I would say it is a solid study,” said Natalie Mrachacz-Kersting, a brain-computer interface researcher at the University of Freiburg in Germany. She was not involved in the study and was aware of the previously retracted papers.

But Brendan Allison, researcher at the University of California San Diego, expressed reservations. “This work, like other work by Birbaumer, should be taken with a massive mountain of salt given his history,” Allison said. He noted that in a paper published in 2017, his own team had described being able to communicate with completely locked-in patients with basic “yes” or “no” answers.

The results hold potential promise for patients in similarly unresponsive situations, including minimally conscious and comatose states, as well as the rising number of people diagnosed with ALS worldwide every year. That number is projected to reach 300,000 by 2040.

“It’s a game-changer,” said Steven Laureys, a neurologist and researcher who leads the Coma Science Group at the University of Liège in Belgium and was not involved in the study. The technology could have ethical ramifications in discussions surrounding physician-assisted suicide for patients in locked-in or vegetative states, he added; “it’s really great to see this moving forward, giving patients a voice” in their own decisions.

Myriad methods have been used to communicate with unresponsive patients. Some involve basic pen-and-paper methods devised by family relatives. In others, a caregiver points to or speaks the names of items and looks for microresponses — blinks or finger twitches from the patient.

In recent years, a new method has taken center stage: brain-computer interface technologies, which aim to translate a person’s brain signals into commands. Research institutes, private companies, and entrepreneurial billionaires like Elon Musk have invested heavily in the technology.

The results have been mixed but compelling: patients moving prosthetic limbs using only their thoughts, and those with strokes, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions communicating once again with loved ones.

What scientists have been unable to do until now, however, is communicate extensively with people like the man in the new study who displayed no movements whatsoever.

In 2017, before becoming totally locked-in, the patient had used eye movements to communicate with his family. Anticipating that he would soon lose even this ability, the family asked for an alternative communication system and approached Chaudhary and Birbaumer, a pioneer in the field of brain-computer interface technology, both of whom worked nearby.

With the man’s approval, Dr. Jens Lehmberg, a neurosurgeon and an author on the study, implanted two tiny electrodes in regions of the man’s brain that are involved in controlling movement. Then, for two months, the man was asked to imagine moving his hands, arms and tongue to see if these would generate a clear brain signal. But the effort yielded nothing reliable.

Birbaumer then suggested using auditory neurofeedback, an unusual technique by which patients are trained to actively manipulate their own brain activity. The man was first presented with a note — high or low, corresponding to yes or no. This was his “target tone” — the note he had to match.

He was then played a second note, which mapped onto brain activity that the implanted electrodes had detected. By concentrating — and imagining moving his eyes, to effectively dial his brain activity up or down — he was able to change the pitch of the second tone to match the first. As he did so, he gained real-time feedback of how the note changed, allowing him to heighten the pitch when he wanted to say yes or lower it for no.

This approach saw immediate results. On the man’s first day trying, he was able to alter the second tone. Twelve days later, he succeeded in matching the second to the first.

“That was when everything became consistent, and he could reproduce those patterns,” said Jonas Zimmermann, a neuroscientist at theWyss Center and an author on the study. When the patient was asked what he was imagining to alter his own brain activity, he replied, “Eye movement.”

Over the next year, the man applied this skill to generate words and sentences. The scientists borrowed a communication strategy that the patient had used with his family when he could still move his eyes.

At this stage, the technology is far too complex for patients and families to operate. Making it more user-friendly and speeding up communication will be crucial, Chaudhary said. Until then, he said, a patient’s relatives will probably be satisfied.

“You have two options: no communication or communication at 1 character per minute,” he said. “What do you choose?”

Perhaps the biggest concern is time. Three years have passed since the implants were first inserted in the patient’s brain. Since then, his answers have become significantly slower, less reliable and often impossible to discern, said Zimmermann, who is now caring for the patient at the Wyss Center.

The cause of this decline is unclear, but Zimmermann thought it probably stemmed from technical issues. For instance, the electrodes are nearing the end of their life expectancy. Replacing them now, however, would be unwise. “It’s a risky procedure,” he said. “All of a sudden, you’re exposed to new kinds of bacteria in the hospital.”

Zimmermann and others at the Wyss Center are developing wireless microelectrodes that are safer to use. The team is also exploring other noninvasive techniques that have proved fruitful in previous studies on patients who are not locked-in. “As much as we want to help people, I think it’s also very dangerous to create false hope,” Zimmermann said.

Read more Health

Jordan News