You have probably heard the advice: One of

the best things you can do to keep healthy — especially as cold and flu season

creeps up — is stay physically active.

اضافة اعلان

This folk wisdom has been around for ages, but until

recently, researchers did not have much data to support the idea. Now,

scientists studying risk factors related to

COVID-19 have turned up some

preliminary evidence about the link between regular exercise and better immune defenses

against disease.

When researchers reviewed 16 studies of people who

stayed physically active during the pandemic, they found that working out was

associated with a lower risk of infection as well as a lower likelihood of

severe COVID. The analysis, published last month in The

British Journal of Sports Medicine, has generated a lot of enthusiasm among exercise scientists,

who say the findings could lead to updated guidelines for physical activity and

health care policy that revolves around exercise as medicine.

Experts who study immunology and infectious disease

are more cautious in their interpretation of the results. But they agree that

exercise can help protect health through several different mechanisms.

Exercise

could bolster immunity in a variety of ways

For decades, scientists have

observed that people who are fit and

physically active seem to have lower rates of several respiratory tract

infections. And when people who work out do get sick, they tend to have less

severe disease, said David Nieman, a professor of health and exercise science

at

Appalachian State University, who was not involved in the recent COVID

review.

“The risk of

severe outcomes and mortality from the common cold, influenza, pneumonia —

they’re all knocked down quite a bit,” Nieman said. “I call it the vaccine-like

effect.”

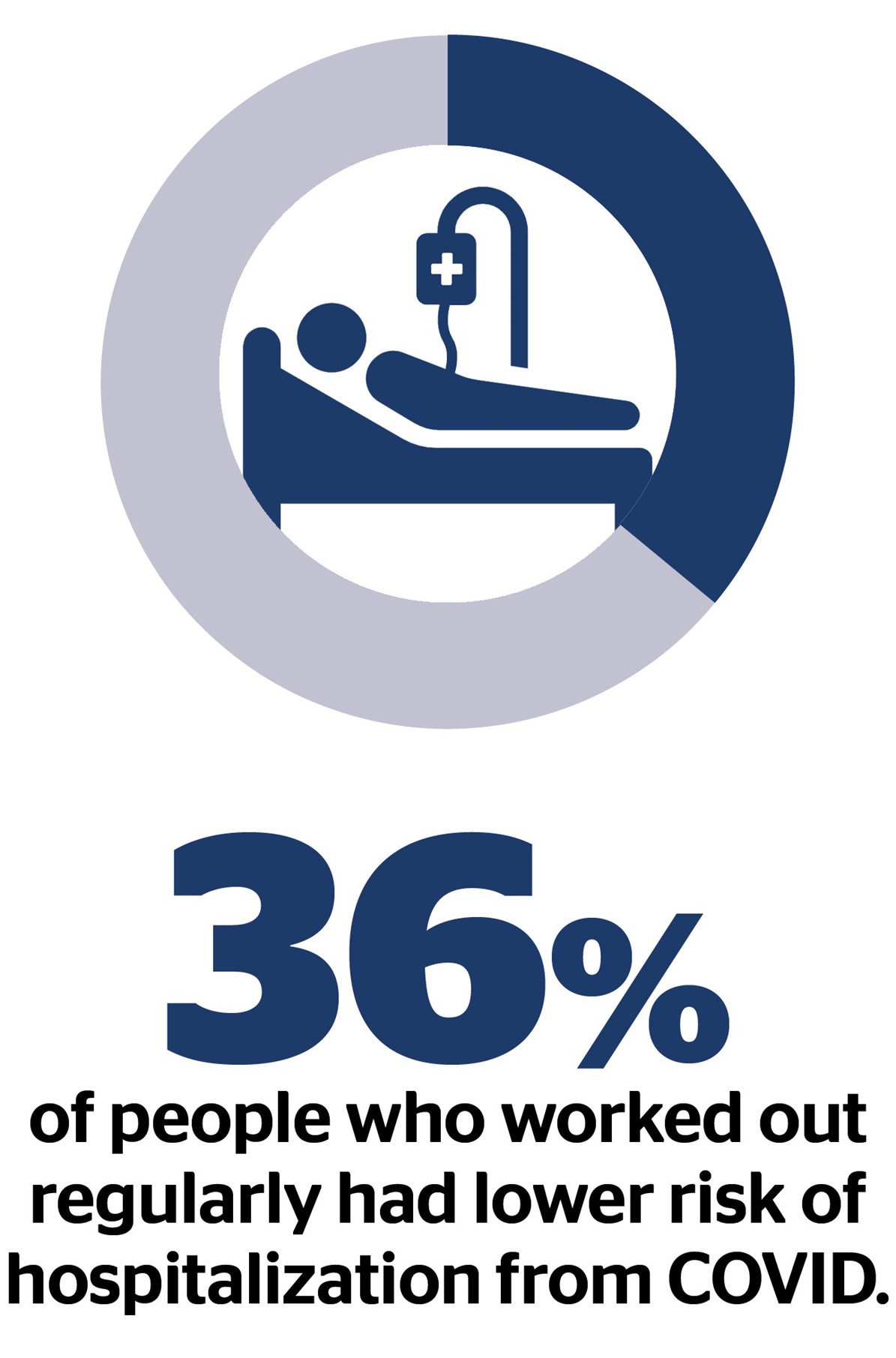

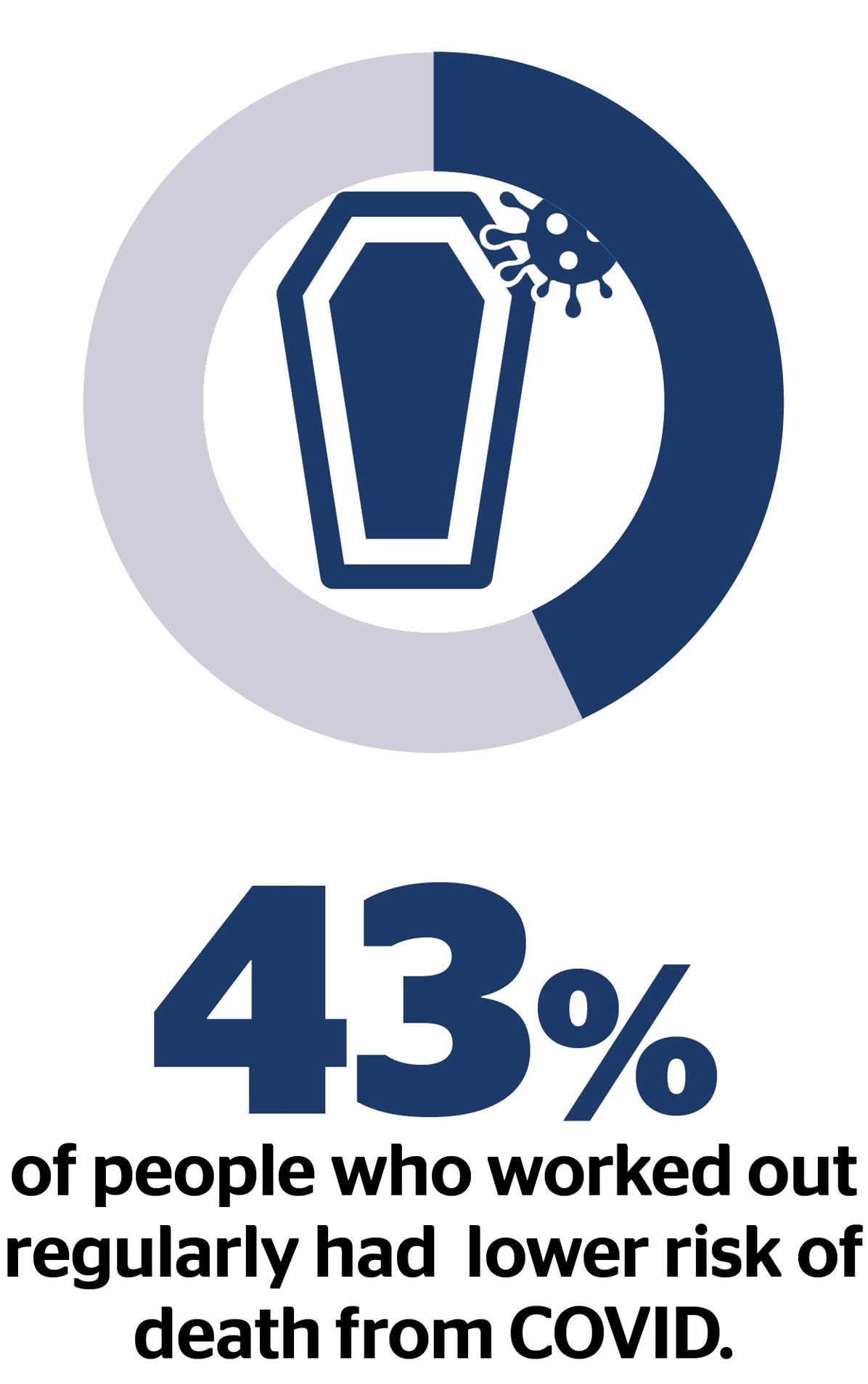

The new

meta-analysis, which looked at studies between November 2019 and March 2022,

found that this effect extends to COVID. People from across the globe who

worked out regularly had a 36 percent lower risk of hospitalization and a 43

percent lower risk of death from COVID compared with those who were not active.

They also had a lower likelihood of getting COVID at all.

People who

followed guidelines recommending at least 150 minutes of moderate activity or 75

minutes of vigorous activity per week seemed to get the most benefit. But even

those who exercised less than that were more protected against illness than

those who did not work out at all.

Researchers

theorize that exercise may help fight off infectious bacteria and viruses by

increasing the circulation of immune cells in your blood, for example. In some

small studies, researchers have also found that the contraction and movement of

muscles releases signaling proteins known as cytokines, which help direct

immune cells to find and fight off infection.

Even if your

levels of cytokines and immune cells taper off two or three hours after you

stop exercising, Nieman said, your immune system becomes more responsive and

able to catch pathogens faster over time if you work out every day. “Your

immune system is primed, and it is in better fighting shape to cope with a

viral load at any given time,” he said.

In healthy

humans, physical activity has also been linked to lower chronic inflammation.

Widespread inflammation can be extremely damaging, even turning your own immune

cells against your body. It is a known risk factor for COVID, Nieman said.

Therefore, it makes sense that reducing inflammation could improve your chances

of fighting off infection, he said.

Research also

shows that exercise may amplify the benefits of some vaccines. People who

worked out right after getting their COVID-19 vaccine, for example, seemed to

produce more antibodies. And in studies of older adults who were vaccinated

early during flu season, those who exercised had antibodies that lasted

throughout the winter.

Exercise provides a

slew of broader health benefits that may help reduce the incidence and severity

of disease, said Dr Stuart Ray, an infectious diseases specialist at

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Building a walk, jog, gym trip, or sport of

choice into your routine is known to help reduce obesity, diabetes and heart

disease, for example, all of which are risk factors for severe influenza and

COVID. Working out can help you get more restful sleep, boost your mood and

improve your insulin metabolism and cardiovascular health, improving your

chances against the flu and COVID. It is hard to know, Ray said, whether the

benefits come from direct changes to the immune system or just overall better

health.

The

research can only tell us

so much

Dr Peter Chin-Hong, an

infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco,

agreed that more research was needed before scientists could pinpoint a

specific mechanism or causal link. In the meantime, he said, it’s important not

to put too much faith in it.

“For now, you can’t say, ‘I’ll go to the gym so that

I can prevent getting COVID,’” Chin-Hong said. The problem with studying the

precise effect of physical activity on immunity is that exercise is not

something that scientists can easily measure on a linear scale, Ray said.

“People exercise in many different ways.”

Study participants typically self-report the amount

and intensity of their exercise, which can often be inaccurate. And just

expecting exercise to be beneficial can provide a powerful placebo effect. As a

result, it can be hard for researchers to tell exactly how much exercise or

what type is ideal for immune function. It’s also quite possible that people

who work out regularly may share other attributes that help them fight off

infections, such as a varied diet or better access to medical care, Ray said.

Beyond that, “there is a huge debate about whether

or not too much exercise makes you more susceptible to infection and illness,”

said Richard Simpson, who studies exercise physiology and immunology at the

University of Arizona.

Marathon runners often report getting sick after

races, Simpson said, and some researchers think that too much vigorous exercise

could inadvertently overstimulate cytokines and inflammation in the body.

Exercising without a break also depletes the body’s glycogen stores, which for

some people could lead to impaired immune function for a few hours or a few

days, depending on their baseline health, he said. And working out in group

settings or attending intense sports training camps could be exposing athletes

to more pathogens. Other experts point out that people who are physically

active might simply keep closer track of their health.

Still, for the average exerciser, early evidence suggests

there may be a protective effect against getting severely ill. But those who

have trouble getting enough exercise or can’t exercise at all for some reason

shouldn’t despair, Ray said. “What helps one person stay healthy compared to

another is a complex mix of factors,” he said.

Read more Health

Jordan News