2 leading theories of consciousness square off

Jordan News

last updated: Jul 03,2023

O a muggy June night in New York City, more than 800

neuroscientists, philosophers, and curious members of the public packed into an

auditorium. They came for the first results of an ambitious investigation into

a profound question: What is consciousness?اضافة اعلان

To kick things off, two friends — David Chalmers, a philosopher, and Christof Koch, a neuroscientist — took the stage to recall an old bet. In June 1998, they had gone to a conference in Bremen, Germany, and ended up talking late one night at a local bar about the nature of consciousness.

For years, Koch had collaborated with Francis Crick, a biologist who shared a Nobel Prize for uncovering the structure of DNA, on a quest for what they called the “neural correlate of consciousness.” They believed that every conscious experience we have — gazing at a painting, for example — is associated with the activity of certain neurons essential for the awareness that comes with it.

Chalmers liked the concept, but he was skeptical that they could find such a neural marker any time soon. Scientists still had too much to learn about consciousness and the brain, he figured, before they could have a reasonable hope of finding it.

Koch wagered that scientists would find a neural correlate of consciousness within 25 years. Chalmers took the bet. The prize would be a few bottles of fine wine.

Recalling the bet from the auditorium stage, Koch admitted that it had been fueled by drinks and enthusiasm.

“When you are young, you have got to believe things will be simple,” he said.

Powerful tools for probing the brain

A lot has happened over the subsequent quarter-century. Neuroscientists and engineers invented powerful new tools for probing the brain, leading to a burst of revealing experiments about consciousness. Some scientists have used brain scans to detect signs of consciousness in people diagnosed as being in a vegetative state, for example, while others have used brain waves to determine when people become unconscious under anesthesia.

Those experiments fostered an explosion of new theories. To winnow them down, the Templeton World Charity Foundation has begun supporting large-scale studies that put different pairs of theories in a head-to-head test, in a process called adversarial collaboration.

And last month, researchers at the New York event unveiled the results of the foundation’s first trial, a matchup of two of the most prominent theories.

Global Workspace Theory

The first, known as the Global Workspace Theory, holds that consciousness is a byproduct of the way we process information. Neuroscientists have long known that most of the signals that come from our senses never reach our awareness. Experiments led by Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France in Paris, suggest that we become aware only of signals that reach the prefrontal cortex, a region in the front of the brain. Dehaene has argued that a special set of neurons there can quickly relay the information across much of the brain, generating consciousness.

“Consciousness is the global availability of information,” Dehaene said.

The Integrated Information Theory

Melanie Boly, a neurologist at the University of Wisconsin, came onstage to explain the other contender: the Integrated Information Theory.

What makes consciousness special, Boly argued, is the way it manages to feel at once rich and unified over time. Brains can produce such a phenomenon thanks to the way neurons are arranged, she said. Clusters of them can process information in particular ways — by identifying the colors or outlines in a picture, for example. But long-range links between those clusters also let them convey information.

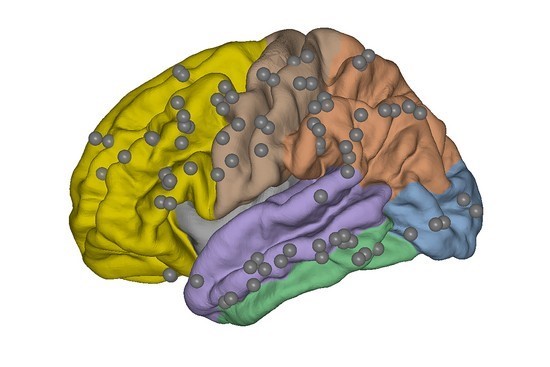

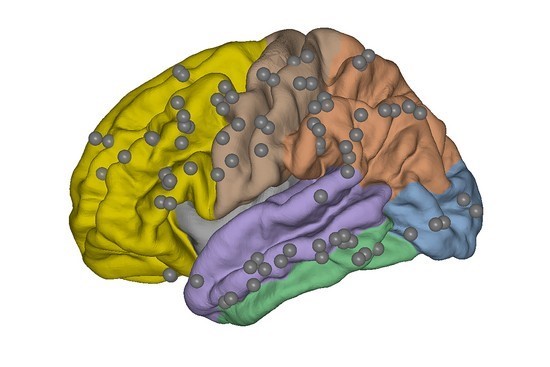

An undated image provided by Aya Khalaf showing results of volunteers in experiments with the Cogitate Consortium that performed tasks of identifying faces and objects in an fMRI brain scanner, which measures the flow of oxygenated blood in the brain. More than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into a Greenwich Village auditorium in June to hear about the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness?

In 2017, Koch, by then working at the Allen Institute in Seattle, invited a dozen experts to the institute to plan experiments that would test the two theories against each other. Chalmers also came from New York University to provide philosophical rigor. They agreed in advance on what the results of each experiment would mean for each theory. And the experiments would be conducted by independent scientists who had not pushed for either theory.

The Cogitate Consortium, as the team called itself, needed two years to prepare the experiment, only to be waylaid by the coronavirus pandemic. In May 2022 the researchers were able to start collecting data.

They asked 256 volunteers to look at a series of faces, letters and shapes and then press a button under certain conditions — if the picture was a face, for example, or a face of a particular person.

Some of the volunteers performed the tasks in an fMRI brain scanner, which measures the flow of oxygenated blood in the brain. Others were observed with magnetoencephalography, which reads magnetic fields in the brain. The researchers also found volunteers who were preparing to undergo brain surgery for epilepsy. They underwent the tests with implants inserted directly in their brains.

The researchers looked for common brain patterns that arose whenever the volunteers had the conscious experience of seeing an object — regardless of what they saw, what their task was or which technology registered their activity.

The two theories made different predictions about which patterns the scientists would see. According to the Global Workspace Theory, the clearest signal would come from the prefrontal cortex because it broadcasts information across the brain. The Integrated Information Theory, on the other hand, predicted that regions with the most complex connections — those in the back of the brain — would be most active.

The timing of the activity could also point to one theory or the other. The Global Workspace Theory predicted that the prefrontal cortex would send out only short bursts of information: one when a picture first appeared, and then another when it disappeared. But the Integrated Information Theory predicted that the back of the brain would be continually active throughout the time that volunteers perceived an object.

Lucia Melloni, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Germany who helped lead the experiments, came to the stage to present the results, with pictures of brains splashed in red, blue and green projected onto a giant screen.

Melloni explained that in some tests there was a clear winner and a clear loser. The activity in the back of the brain endured through the entire time that volunteers saw an object, for example. Score one for the Integrated Information Theory. But in other tests, the Global Workspace Theory’s predictions were borne out.

“The current experiment is enough to show that neither theory is presently sufficient,” said Anil Seth, a neuroscientist at the University of Sussex in England.

But the 25-year bet, at least, has been resolved: No one has found a clear neural correlate of consciousness. Koch ended the evening by carrying to the stage a wooden box full of wine. He pulled out a 1978 bottle of Madeira and gave it to Chalmers.

Then he challenged his friend to a new bet, this time double or nothing: a brain marker of consciousness by 2048.

Chalmers instantly shook on the bet, despite the questionable odds that either will still be alive to see the outcome.

“I hope I lose,” he said. “But I suspect I will win.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News

To kick things off, two friends — David Chalmers, a philosopher, and Christof Koch, a neuroscientist — took the stage to recall an old bet. In June 1998, they had gone to a conference in Bremen, Germany, and ended up talking late one night at a local bar about the nature of consciousness.

For years, Koch had collaborated with Francis Crick, a biologist who shared a Nobel Prize for uncovering the structure of DNA, on a quest for what they called the “neural correlate of consciousness.” They believed that every conscious experience we have — gazing at a painting, for example — is associated with the activity of certain neurons essential for the awareness that comes with it.

Chalmers liked the concept, but he was skeptical that they could find such a neural marker any time soon. Scientists still had too much to learn about consciousness and the brain, he figured, before they could have a reasonable hope of finding it.

Koch wagered that scientists would find a neural correlate of consciousness within 25 years. Chalmers took the bet. The prize would be a few bottles of fine wine.

Recalling the bet from the auditorium stage, Koch admitted that it had been fueled by drinks and enthusiasm.

“When you are young, you have got to believe things will be simple,” he said.

Powerful tools for probing the brain

A lot has happened over the subsequent quarter-century. Neuroscientists and engineers invented powerful new tools for probing the brain, leading to a burst of revealing experiments about consciousness. Some scientists have used brain scans to detect signs of consciousness in people diagnosed as being in a vegetative state, for example, while others have used brain waves to determine when people become unconscious under anesthesia.

Those experiments fostered an explosion of new theories. To winnow them down, the Templeton World Charity Foundation has begun supporting large-scale studies that put different pairs of theories in a head-to-head test, in a process called adversarial collaboration.

And last month, researchers at the New York event unveiled the results of the foundation’s first trial, a matchup of two of the most prominent theories.

Global Workspace Theory

The first, known as the Global Workspace Theory, holds that consciousness is a byproduct of the way we process information. Neuroscientists have long known that most of the signals that come from our senses never reach our awareness. Experiments led by Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France in Paris, suggest that we become aware only of signals that reach the prefrontal cortex, a region in the front of the brain. Dehaene has argued that a special set of neurons there can quickly relay the information across much of the brain, generating consciousness.

“Consciousness is the global availability of information,” Dehaene said.

The Integrated Information Theory

Melanie Boly, a neurologist at the University of Wisconsin, came onstage to explain the other contender: the Integrated Information Theory.

What makes consciousness special, Boly argued, is the way it manages to feel at once rich and unified over time. Brains can produce such a phenomenon thanks to the way neurons are arranged, she said. Clusters of them can process information in particular ways — by identifying the colors or outlines in a picture, for example. But long-range links between those clusters also let them convey information.

An undated image provided by Aya Khalaf showing results of volunteers in experiments with the Cogitate Consortium that performed tasks of identifying faces and objects in an fMRI brain scanner, which measures the flow of oxygenated blood in the brain. More than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into a Greenwich Village auditorium in June to hear about the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness?

In 2017, Koch, by then working at the Allen Institute in Seattle, invited a dozen experts to the institute to plan experiments that would test the two theories against each other. Chalmers also came from New York University to provide philosophical rigor. They agreed in advance on what the results of each experiment would mean for each theory. And the experiments would be conducted by independent scientists who had not pushed for either theory.

The Cogitate Consortium, as the team called itself, needed two years to prepare the experiment, only to be waylaid by the coronavirus pandemic. In May 2022 the researchers were able to start collecting data.

They asked 256 volunteers to look at a series of faces, letters and shapes and then press a button under certain conditions — if the picture was a face, for example, or a face of a particular person.

Some of the volunteers performed the tasks in an fMRI brain scanner, which measures the flow of oxygenated blood in the brain. Others were observed with magnetoencephalography, which reads magnetic fields in the brain. The researchers also found volunteers who were preparing to undergo brain surgery for epilepsy. They underwent the tests with implants inserted directly in their brains.

The researchers looked for common brain patterns that arose whenever the volunteers had the conscious experience of seeing an object — regardless of what they saw, what their task was or which technology registered their activity.

The two theories made different predictions about which patterns the scientists would see. According to the Global Workspace Theory, the clearest signal would come from the prefrontal cortex because it broadcasts information across the brain. The Integrated Information Theory, on the other hand, predicted that regions with the most complex connections — those in the back of the brain — would be most active.

The timing of the activity could also point to one theory or the other. The Global Workspace Theory predicted that the prefrontal cortex would send out only short bursts of information: one when a picture first appeared, and then another when it disappeared. But the Integrated Information Theory predicted that the back of the brain would be continually active throughout the time that volunteers perceived an object.

Lucia Melloni, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Germany who helped lead the experiments, came to the stage to present the results, with pictures of brains splashed in red, blue and green projected onto a giant screen.

Melloni explained that in some tests there was a clear winner and a clear loser. The activity in the back of the brain endured through the entire time that volunteers saw an object, for example. Score one for the Integrated Information Theory. But in other tests, the Global Workspace Theory’s predictions were borne out.

“The current experiment is enough to show that neither theory is presently sufficient,” said Anil Seth, a neuroscientist at the University of Sussex in England.

But the 25-year bet, at least, has been resolved: No one has found a clear neural correlate of consciousness. Koch ended the evening by carrying to the stage a wooden box full of wine. He pulled out a 1978 bottle of Madeira and gave it to Chalmers.

Then he challenged his friend to a new bet, this time double or nothing: a brain marker of consciousness by 2048.

Chalmers instantly shook on the bet, despite the questionable odds that either will still be alive to see the outcome.

“I hope I lose,” he said. “But I suspect I will win.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News