In 1937, a US drug company introduced a new elixir to treat

strep throat — and unwittingly set off a public health disaster. The product,

which had not been tested in humans or animals, contained a solvent that turned

out to be toxic. More than 100 people died.

اضافة اعلان

The following year, Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug and

Cosmetic Safety Act, requiring pharmaceutical companies to submit safety data

to the US Food and Drug Administration before selling new medications, helping

to usher in an era of animal toxicity testing.

Now, a new chapter in drug development may be beginning. The FDA

Modernization Act 2.0, signed into law late last year, allows drugmakers to collect

initial safety and efficacy data using high-tech new tools, such as

bioengineered organs, organs on chips, and even computer models, instead of

live animals. Congress also allocated $5 million to the FDA to accelerate the

development of alternatives to animal testing.

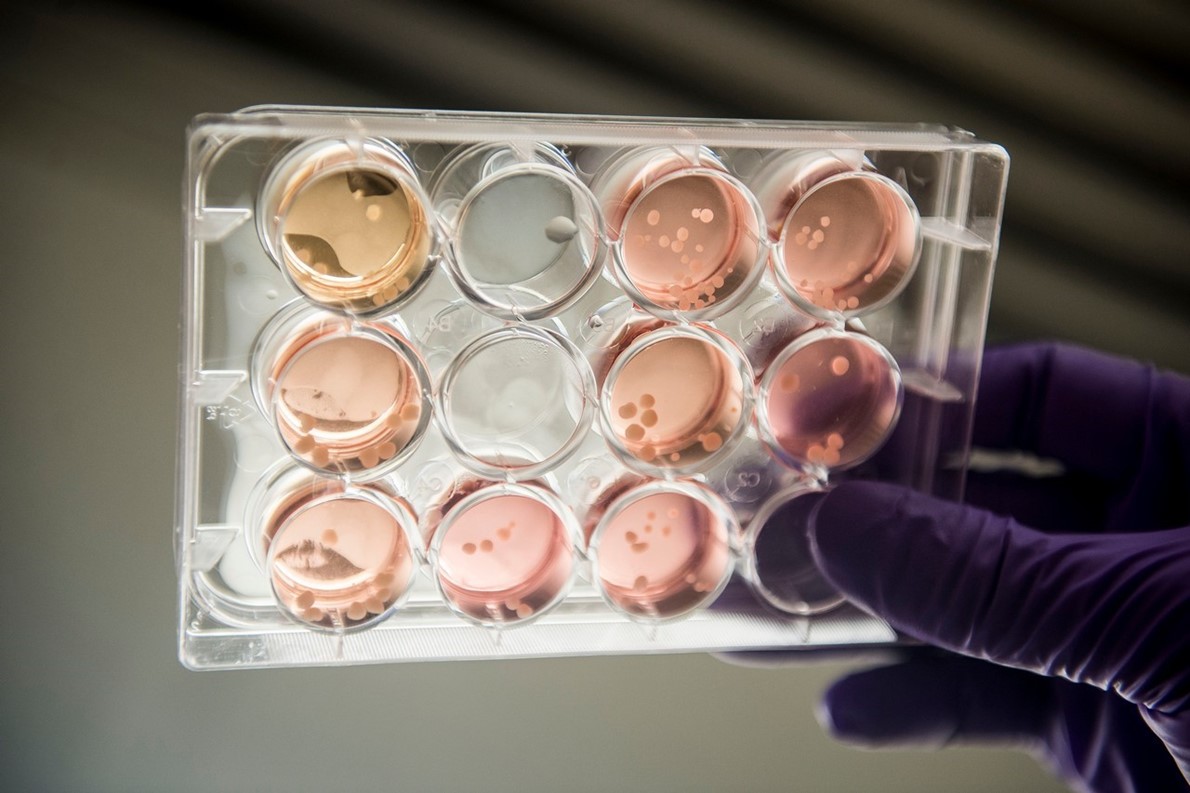

Cultures of cerebral

organoids in a lab at the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Cultures of cerebral

organoids in a lab at the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Other agencies and countries are making similar shifts. In 2019,

the US Environmental Protection Agency announced that it would reduce, and

eventually aim to eliminate, testing on mammals. In 2021, the European

Parliament called for a plan to phase out animal testing.

These moves have been driven by a confluence of factors,

including evolving views of animals and a desire to make drug development

cheaper and faster, experts said. But what is finally making them feasible is

the development of sophisticated alternatives to animal testing.

It is still early for these technologies, many of which need to

be refined, standardized and validated before they can be used routinely in

drug development. And even advocates for these alternatives acknowledge that

animal testing is not likely to disappear anytime soon.

But momentum is building for non-animal approaches, which could

ultimately help speed drug development, improve patient outcomes, and reduce

the burdens borne by lab animals, experts said.

“Animals are simply a surrogate for predicting what’s going to

happen in a human,” said Nicole Kleinstreuer, director of the National

Toxicology Program Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative

Toxicological Methods.

“If we can get to a place where we actually have a fully

human-relevant model,” she added, “then we don’t need the black box of animals

anymore.”

Animal attitudesAnimal rights groups have been lobbying for a reduction in

animal testing for decades, and they have found an increasingly receptive

public. In a 2022 Gallup poll, 43 percent of Americans said that medical

testing on animals was “morally wrong,” up from 26 percent in 2001.

Reducing animal testing “matters to so many people for so many

different reasons,” said Elizabeth Baker, the director of research policy at

the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, a nonprofit group that

advocates for alternatives to animal testing. “Animal ethics is actually quite

a big driver.”

But it is not the only one. Animal testing is also

time-consuming, expensive and vulnerable to shortages. Drug development, in

particular, is rife with failures, and many medications that appear promising

in animals do not pan out in humans. “We’re not 70-kilogram rats,” said Dr

Thomas Hartung, who directs the Johns Hopkins Center for Alternatives to Animal

Testing.

Moreover, some cutting-edge new treatments are based on

biological products, such as antibodies or fragments of DNA, which may have

targets that are specific to humans.

“There’s a lot of pressure, not just for ethical reasons, but

also for these economical reasons and for really closing safety gaps, to adapt

to things which are more modern and human relevant,” Hartung said.

In 2019, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced that it would reduce, and eventually aim to eliminate, testing on mammals. In 2021, the European Parliament called for a plan to phase out animal testing.

(Hartung is the named inventor on a Johns Hopkins University

patent on the production of brain organoids. He receives royalty shares from,

and consults for, the company that has licensed the technology.)

Brave new biologyIn recent years, scientists have developed more sophisticated

ways to replicate human physiology in the laboratory.

They have learned how to coax human stem cells to assemble

themselves into a small, three-dimensional clump, known as an organoid, that

displays some of the same basic traits as a specific human organ, such as a

brain, a lung, or a kidney.

Scientists can use these mini-organs to study the underpinnings

of disease or to test treatments, even on individual patients. In a 2016 study,

researchers made mini-guts from cell samples from patients with cystic fibrosis

and then used the organoids to predict which patients would respond to new

drugs.

Scientists are also using 3D printers to produce organoids at

scale and to print strips of other kinds of human tissue, such as skin.

Another approach relies on “organs on a chip”. These devices,

which are roughly the size of AA batteries, contain tiny channels that can be

lined with different kinds of human cells. Researchers can pump drugs through

the channels to simulate how they might travel through a particular part of the

body.

Compound computationsNot all the new tools require real cells. There are also

computational models that can predict whether a compound with certain chemical

characteristics is likely to be toxic, how much of it will reach different

organs and how quickly it will be metabolized.

The models can be adjusted to represent different types of

patients. For instance, a drug developer could test whether a medication that

works in young adults would be safe and effective in older adults, who often

have reduced kidney function.

“If you can identify the problems as early as possible using a

computational model that saves you going down the wrong route with these

chemicals,” said Judith Madden, an expert on “in silico,” or computer-based,

chemical testing at Liverpool John Moores University. (Madden is also the

editor-in-chief of the journal Alternatives to Laboratory Animals.)

Some of the approaches have been around for years, but advances in

computing technology and artificial intelligence are making them increasingly

powerful and sophisticated, Madden said.

Virtual cells have also shown promise. For instance, researchers

can model individual human heart cells using “a set of equations that describe

everything that’s going on in the cell,” said Elisa Passini, the program

manager for drug development at the National Center for the Replacement,

Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research, or NC3Rs, in Britain.

Reduce or replaceMany potential animal alternatives will require more investment

and development before they can be used widely, experts said. They also have

limitations of their own. Computer models, for instance, are only as good as

the data they are built on, and more data is available on certain types of

compounds, cells, and outcomes than others.

For now, these alternative methods are better at predicting

relatively simple, short-term outcomes, such as acute toxicity, than

complicated, long-term ones, such as whether a chemical might increase the risk

of cancer when used over months or years, scientists said.

And experts disagreed on the extent to which these alternative

approaches might replace animal models. “We’re absolutely working toward a

future where we want to be able to fully replace them,” Kleinstreuer said,

although she acknowledged that it might take decades, “if not centuries.”

But others said that these technologies should be viewed as a

supplement to, rather than a replacement for, animal testing. Drugs that prove

promising in organoids or computer models should still be tested in animals,

said Matthew Bailey, president of the National Association for Biomedical

Research, a nonprofit group that advocates for the responsible use of animals

in research.

“Researchers still need to be able to see everything that

happens in a complex mammalian organism before being allowed to move to the

human clinical trials,” he said.

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News