Dakota the “dino mummy” has fascinated

paleontologists and the public since part of the fossil was first untombed in

North Dakota with some of its skin preserved.

اضافة اعلان

Scientists are not finished making discoveries about

Dakota, a duck-billed dinosaur, and they recently unlocked a well-preserved

foot, a forelimb, and more of its tail from the stone encasing the fossil.

While more work needs to be done to fully expose this 66- to

67-million-year-old mummy, those parts of its anatomy alone are already

challenging some paleontological theories.

A paper published recently in the journal

PLOS ONE

focuses on those recently exposed body parts and offers new insight into how

fossil mummies like Dakota might have survived. The new research even suggests

there may be far more mummified skin out there to find in the fossil record and

study than previously believed, if only paleontologists look in the right

places.

Before this research, mummified dinosaurs were said

to form in one of two ways: They were either buried rapidly after death, or

they remained intact in an arid landscape long enough for the carcass to be

preserved.

But further studies into the sediments surrounding

the fossil suggest that Dakota lived not in a dry, arid place, but in a humid,

wet environment. Its body lay close to a water source in its final moments.

Bite marks recently identified on its bone and skin also indicate significant

scavenging on this animal from a variety of carrion feeders, including

ancestors of modern crocodiles and perhaps carnivorous dinosaurs like young

T-rex or Dakotaraptors. If this dinosaur died near water and was scavenged by

predators, why did its soft skin fail to rot away?

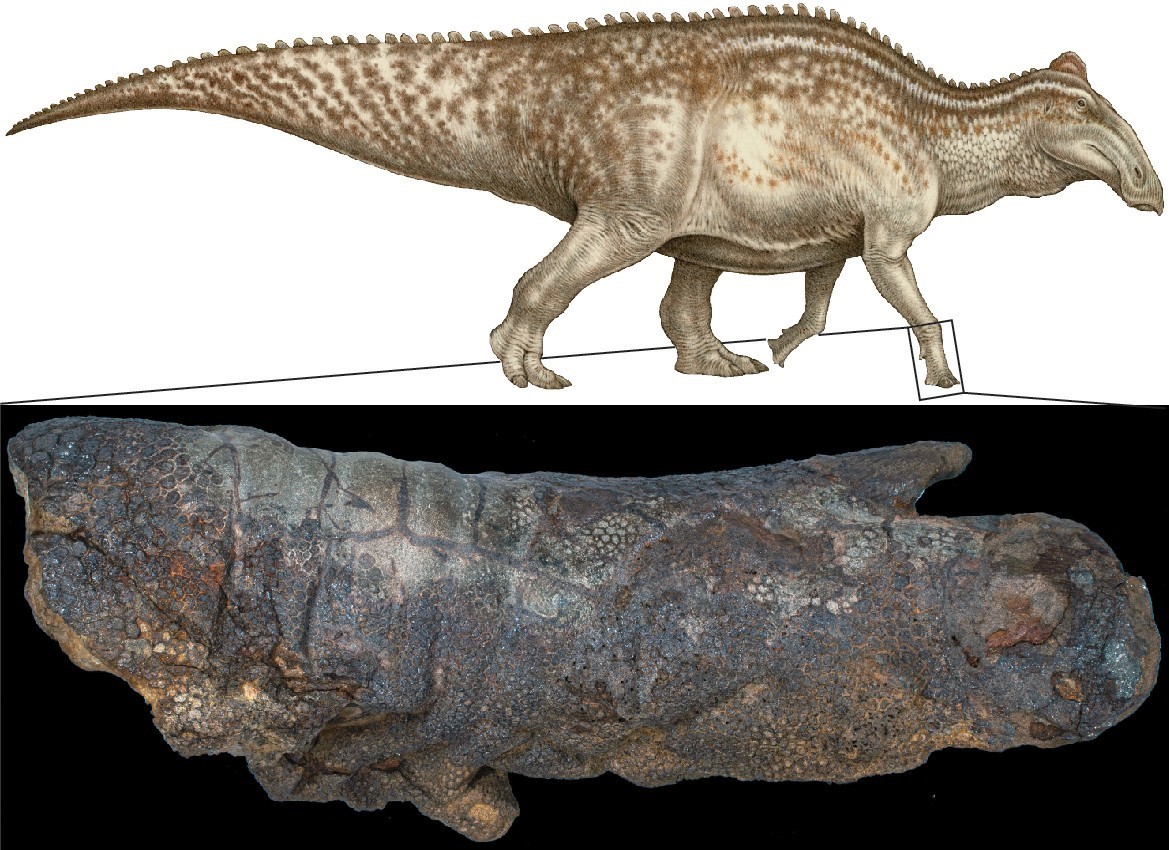

A life reconstruction of a hadrosaur (top) and its mummified forelimb (below).

A life reconstruction of a hadrosaur (top) and its mummified forelimb (below).

A new answer to this question started with Stephanie

Drumheller, a paleontologist and an expert in bite marks at the University of

Tennessee, Knoxville. CT scans showed the preserved skin was deflated, rather

than compressed by sedimentary stone pressed down on it.

This was difficult to explain until Drumheller came

to a realization: She had seen something like this in other preserved remains.

But not dinosaur fossils. Rather, in human and mammalian bodies that were used

in forensic anthropological research.

Human and mammalian remains can in some situations

remain preserved in a wet environment for months. When these remains last it is

because small scavengers burrow into the body, opening a pathway for liquids

and gasses to exit, and the skin eventually dries out and is preserved.

“This is weird and unexpected if you’ve only read

the paleontological literature dealing with mummies,” Drumheller said. “But

it’s really in line with the forensic anthropological literature.”

The idea that ‘some degree of scavenging might favor the mummification of skin’ is ‘an exciting discovery’

Incomplete scavenging, the team asserts, can

actually help preserve an animal, even a dinosaur. Large predators may take

chunks out of the animal, but they’re after the more nutritious muscle and

internal organs. The gouges they make in pursuit of that meal also allow gasses

and liquids to escape the body. What remains on the landscape is a body of skin

and bones that then slowly desiccates and deflates, eventually preserved for

the eons.

The idea that “some degree of scavenging might favor

the mummification of skin” is “an exciting discovery”, said Fion Waisum Ma, a

vertebrate paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

who was not involved in the research. “This study is comprehensive,” she said,

“and gives us a new perspective on how soft tissue preservation may have

occurred in dinosaurs and more generally in land vertebrates”.

Anecdotally, the team heard a number of stories from

colleagues finding more patches of fossilized skin in the field than they

expected, particularly when excavating hadrosaurs. Finding such fossils seemed

to contradict the conventional wisdom behind dinosaur mummification, but until

now, the scientific literature did not offer any other explanation for what

researchers were observing.

Clint Boyd, a co-author of the study and a

paleontologist at the North Dakota Geologic Survey, said he hoped the study

would prompt many of his colleagues to say: “Yeah, of course. That makes sense

with what we’re seeing.”

For the past

three years, removing more of Dakota’s fossils from stone has been the work of

Mindy Householder, another co-author of the study and a preparator at the State

Historical Society of North Dakota. Her early work as a fossil preparator did

not even include the possibility of fossil skin. Locating the bone within and

removing it from the stone in which it was preserved, she said, was the focus

of her training, and such methods may result in preserved skin being lost. It

was not until working on Dakota that this began to change.

The evidence she and her colleagues discovered, she

said, may mean that “skin is more common than we thought it was”. And this, she

added, “definitely should change” how fossils are treated.

Skin “could be there!” she said. “As a community,

maybe we need to be more aware of that.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News