Mention the ocean, and it is hard not to think of jaws.

The deep waters contain many tooth-lined mouths: the bear-trap maws of

sharks and dolphins, the slack lips of shoaling and reef fish, the baleen-filter gape

of enormous whales. Jawed fish eventually crawled out of the seas millions of

years ago and gave rise to the jawboning vertebrates we are today.

اضافة اعلان

But when did such an evolutionary innovation arise? A pair of

fossil beds discovered in

Southern China suggest that the answer may lie tens

of millions of years deeper into the past than previously thought. The findings

— which include beautifully preserved new species of early fish, the

oldest-known vertebrate teeth and a lot of fish with armor — were published in

September across four papers in Nature.

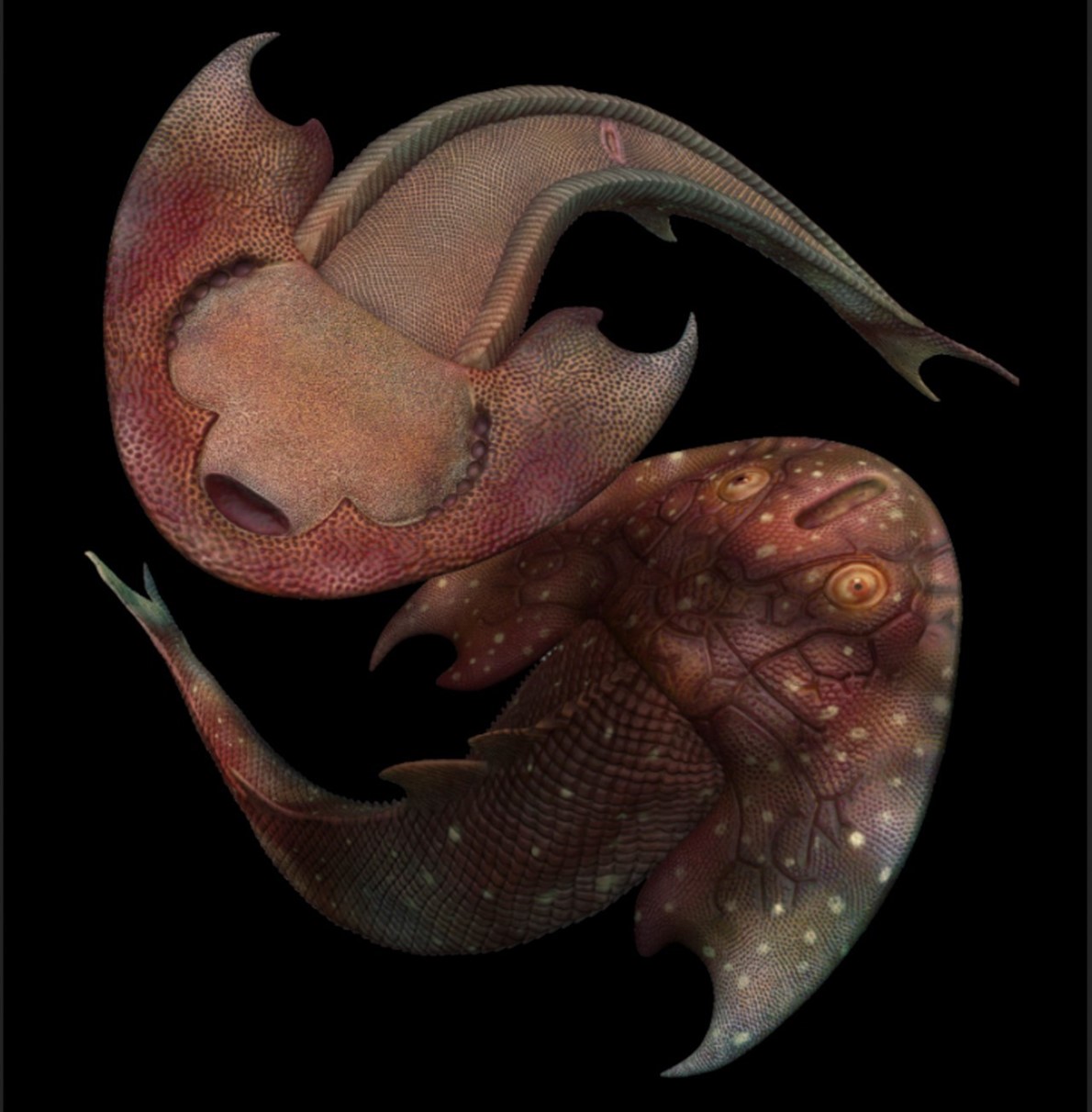

From top right going clockwise: Shenacanthus vermiformis,

Xiushanosteus mirabilis, Tujiaaspis vividus, Qianodus duplicis, and

Fanjingshania renovata, five newly discovered jawed fishes.

From top right going clockwise: Shenacanthus vermiformis,

Xiushanosteus mirabilis, Tujiaaspis vividus, Qianodus duplicis, and

Fanjingshania renovata, five newly discovered jawed fishes.

“This is a step change in where we’re thinking about these

events in the chronology of vertebrate evolution,” said Matt Friedman, a

paleontologist at the

University of Michigan who was not involved in the

research but wrote a perspective article that accompanied the Nature papers.

Jawed fish explode into the fossil record 419–359 million years

ago during a period known as the age of fish, or the Devonian. Fish of this era

all have “their identities clearly written on their bodies,” said Michael

Coates, a paleobiologist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in

the new papers. They include ancient groups like jawless fish, lineages of

early jawed fish called placoderms, ascendant newcomers like cartilaginous and

bony fish, and the first fishes to hop onto land.

A Shenacanthus vermiformis, a cartilaginous

fish related to sharks and rays.

A Shenacanthus vermiformis, a cartilaginous

fish related to sharks and rays.

This sudden diversity of jawed fish — also called gnathostomes —

has long led scientists to suspect that their origins must lie deeper in the

fossil record, a period known as the Silurian, said Per Ahlberg, a

paleontologist at

Uppsala University in Sweden and an author on one of the

papers. But until recently, the number of useful Silurian gnathostome fossils

could be counted on one hand.

A decade ago, researchers set out to systematically survey the

425-million-year-old rocks of the late Silurian period in China, said Gai

Zhikun, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and an author on

one of the papers. They were rewarded with complete fossils of early jawed

fish.

Encouraged, they delved into older rocks. In 2020 these fishing

expeditions got a bite: a pair of deposits outside of Chongqing.

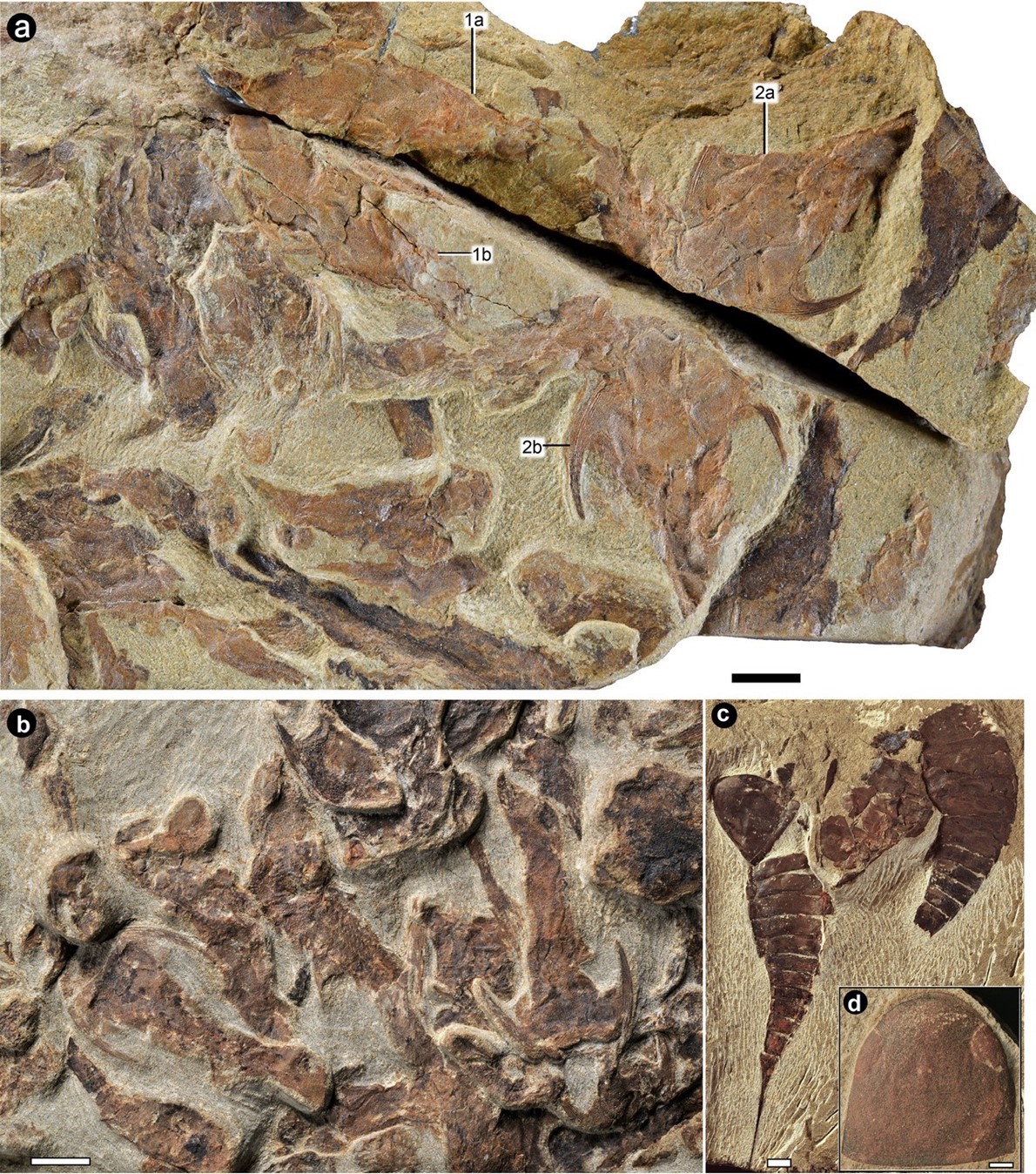

Fish fossils from a Chongqing fossil deposit.

Fish fossils from a Chongqing fossil deposit.

The two fossil beds are separated by a few million years in

time, each with a different complement of species.

The 436-million-year-old bed contains “little fishtank-sized

fishes”, Ahlberg said, only a few centimeters long, which represent the

oldest-known complete jawed fish. Most are of a flat, armored placoderm species

named Xiushanosteus mirabilis, which most likely lived on the seafloor. Also

present is Shenacanthus vermiformis, a cartilaginous fish related to sharks and

rays, but with armor plates resembling those of unrelated placoderms — a find

that suggests early sharklike species retained the armor-plates present in

earlier branches of the fish family tree.

Philip Donoghue, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol

and an author of one of the papers, says the most remarkable specimen from the

site is a jawless fish called Tujiaaspis vividus. Thousands of head shields

from the species’ family are known from the fossil record, but Tujiaaspis

preserves the first known body. It comes with a surprise: a set of paired fins

jutting out from the skull, which Donoghue and his colleagues suggest is a

likely precursor of the pectoral and pelvic fins found in gnathostomes, which

for fish that moved onto land gave rise to arms and legs. Previously,

researchers believed the two sets of fins evolved separately between jawless

and jawed fish.

A Tujiaaspis vividus, a newly discovered jawed

fish.

A Tujiaaspis vividus, a newly discovered jawed

fish.

“It overturns conventional wisdom on how paired appendages

originated,” Donoghue said.

The second site, at 439 million years old, preserved more

important fossils. One paper describes a collection of spines, scales, and

head-plates from an animal named Fanjingshania renovata, all of them

dead-ringers for later examples of cartilaginous fish. Another records a whirl

of connected teeth — the oldest yet known from a vertebrate — from a fish named

Qianodus duplicis. Both animals belong firmly to the branch of jawed fish

called the chondrichthyans, the group of cartilaginous fish that include modern

sharks, rays, and ratfish. (Bony fish like salmon and humans are the other

branch.)

The presence of shark relatives at the site suggests that the

split between cartilaginous and bony fish had already occurred by the early

Silurian, Friedman said. Taken together, both sites push the origin of

vertebrate jaws and teeth back by almost 14 million years.

“It’s a big shift from the consensus chronology,” Friedman said,

which will force a drastic reconsideration of early marine ecosystems.

A Fanjingshania renovata, a newly discovered

jawed fish.

A Fanjingshania renovata, a newly discovered

jawed fish.

Jawed fish now seem to have originated as early as the Great

Ordovician Biodiversification, a period around 485 million to 445 million years

ago when marine invertebrates ruled. The few known fish from that period are

jawless and generally unprepossessing, Coates said. “They look like

armor-plated tadpoles,” he said. “So the last thing you’d expect is for

proto-sharks and proto-bony fish to be swanning around at the same time.”

A Qianodus duplicis, a newly discovered jawed fish. The

Qianodus duplicis, related to present-day sharks, rays, and ratfish, had

connected teeth — the oldest yet known example in a vertebrate.

A Qianodus duplicis, a newly discovered jawed fish. The

Qianodus duplicis, related to present-day sharks, rays, and ratfish, had

connected teeth — the oldest yet known example in a vertebrate.

As paleontologists continue to dig deeper into early Silurian

rocks in China, they’ve uncovered even more fish species. When it comes to the

earliest jawed fish, researchers may soon find that they’ll need a bigger boat.

“It’s highly likely that there will be more discoveries,”

Ahlberg said. “It’s an overused phrase, but I mean it: This promises to

completely revolutionize our understanding of the earliest phase of jawed

vertebrate evolution.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News