On a Saturday evening in August, two

Ukrainian mathematicians, Maryna Viazovska and Masha Vlasenko, set out on a

19-hour train trip from Warsaw, Poland, to Kyiv, Ukraine. They were en route to

a conference titled “Numbers in the Universe: Recent Advances in Number Theory

and Its Applications.” Symbolically, the journey served to plant a flag.

اضافة اعلان

The event marked the opening of the

International Center for Mathematics in Ukraine, or ICMU, which was established

on paper in November. “The goal is to bring the world of mathematics to Ukraine

and open, or reopen, Ukrainian science for the world,” said Viazovska, of the

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. She won a Fields Medal in

2022 and serves as scientific lead on the center’s coordination committee.

“Making this investment is of course

meaningful from a strictly scientific point of view,” said Jean-Pierre

Bourguignon, the chair of the center’s supervisory board and a former president

of the European Research Council, “but also in terms of how Ukraine can

redevelop after the end of the war in a way which is meaningful economically.

Highly trained mathematical people are going to be a key factor.”

The center’s first major donor, XTX

Markets, an algorithmic trading company in London, promised to match funds

raised up to 1 million euros for a year. So far, the French government has

contributed 200,000 euros.

Masha Vlasenko, a professor at the Institute of

Mathematics of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10,

2023.

Masha Vlasenko, a professor at the Institute of

Mathematics of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10,

2023.

The center’s inaugural conference drew 75

participants at the Kyiv School of Economics, a venue chosen for its bomb shelter,

which was suitable for lectures and equipped with whiteboards, backup power and

internet. (The search is on for a permanent home in the city.) Simultaneously,

via live video, the conference proceeded in Warsaw, at the Stefan Banach

International Mathematical Center, where 110 participants attended. The

parallel locations were necessary since martial law prevented adult Ukrainian

men ages 18 to 60 from traveling outside the country, and the organizers were

hesitant to invite foreign participants into a war zone.

No Such Place Until Now

Vlasenko, from the Institute of Mathematics

of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw and a member of the ICMU

coordination committee, had long dreamed of creating a mathematics research

institute in Ukraine. The catalyst was the war, she said, coupled with

Viazovska’s Fields Medal. On the way to the conference — while waiting for a

midnight connecting train at the station in Chelm, Poland — the two scholars

had coffee with a few more conference-bound mathematicians and discussed

growing up in Ukraine studying mathematics.

“The generations change, but they have the

same feeling,” Vlasenko said. There is a deep tradition of science and math in

the country, but in the past several decades, in part because of underfunding,

there has been a massive brain drain, she said, as students and researchers

feel they must go elsewhere to advance.

Viazovska, who is originally from Kyiv,

attended the Technical University of Kaiserslautern in Germany for her master’s

studies. “I was very young, and it felt like an adventure,” she said. “I had

the idea I will go there, I will study, and then I will come back. I didn’t

realize that it was very difficult to come back.” She went on to do her

doctorate at the University of Bonn in Germany.

Vlasenko, who is also from Kyiv, received

her doctorate from the Institute of Mathematics of the National Academy of

Sciences of Ukraine and then was a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for

Mathematics in Bonn. When she first saw the library there, “it turned my world

upside down,” she said. “There is no such place in Ukraine.” She added, “There

is no such place until now.”

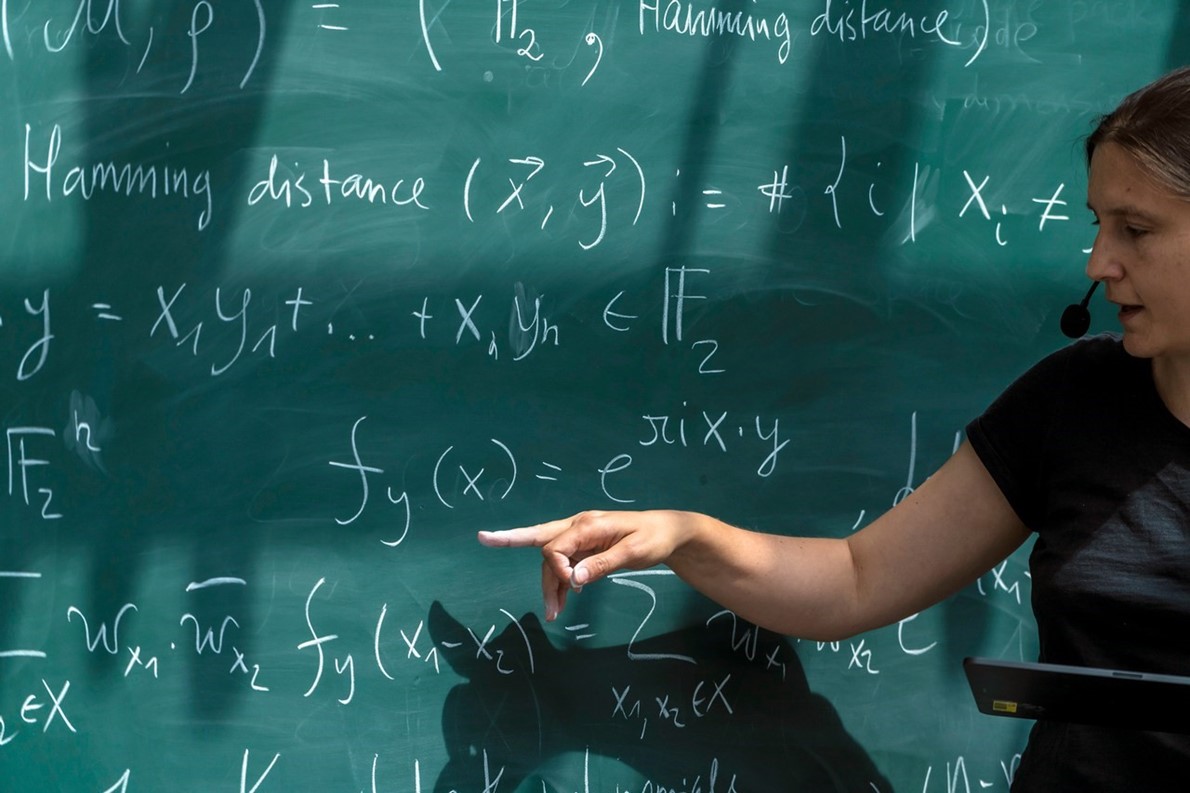

Participants listen to a lecture at the Numbers

in the Universe conference, the first hosted by the newly-formed International

Centre for Mathematics in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10, 2023.

Participants listen to a lecture at the Numbers

in the Universe conference, the first hosted by the newly-formed International

Centre for Mathematics in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10, 2023.

About three-quarters of the conference

participants were students and young mathematicians, and a series of

multilecture courses and problem-solving sessions was directed at them. In

Kyiv, Viazovska delivered four lectures on sphere packing. From Warsaw, Terence

Tao, of UCLA, and a 2006 Fields medalist, taught a course on prime numbers and

related topics.

“It was a surprisingly pleasant and normal

mathematics conference,” Tao noted in an email afterward. The focus was not the

war but the mathematics, he said, and the two sites shared lighthearted banter:

“‘Kyiv, do you have any questions?’ No, Kyiv understood everything. ‘Warsaw, do

you have any questions?’”

Yulia’s Dream

The conference’s youngest participants were

two students from Yulia’s Dream, a new online enrichment program for Ukrainian

high schoolers who excel in math.

The program is named in memory of Yulia

Zdanovska, a talented mathematician and computer scientist, and a teacher with

Teach for Ukraine, who was killed in March 2022 at the age of 21 during Russian

shelling in her home city of Kharkiv. Yulia’s Dream is organized through the

mathematics department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as an

offshoot of a similar program for American students, the Program for Research

in Mathematics, Engineering and Science for High School Students, or PRIMES.

The goal is to expose students to the world

community of research mathematics by, for instance, connecting them with

early-career mentors in the United States and Europe. “Mathematics is often

misunderstood as a solitary endeavor,” said Slava Gerovitch, a historian of

science at MIT and the director and a co-founder of PRIMES. “One cannot be a

successful mathematician without being integrated into these international

networks for the exchange of knowledge.”

From 260 applicants to Yulia’s Dream last

year, 48 students were selected. They worked in small groups on reading

studies; some did nine-month group research projects and wrote papers for

submission to math journals.

“Now I understand better what real mathematicians

do,” said Maryna Spektrova, 15, of Kharkiv. Spektrova, who was a spare for the

Ukrainian team at the International Mathematical Olympiad this year, observed

that while such contests entail solving a problem in hours, research problems

can take months or years.

Ivan Balashov, 16, from Dnipro, found that

during the war, opportunities like the olympiad and Yulia’s Dream were

important for a student’s sense of achievement and confidence.

“Self-realization is one of the main concepts which makes the person freer,” he

said in an email. “After all, it is what we are fighting for — freedom.”

Maryna Viazovska, a professor of mathematics at

the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne and a 2022 Fields

medalist, delivers remarks at the opening of the International Center for

Mathematics in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10, 2023.

Maryna Viazovska, a professor of mathematics at

the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne and a 2022 Fields

medalist, delivers remarks at the opening of the International Center for

Mathematics in Kyiv, Ukraine on Aug. 10, 2023.

Yehor Avdieiev, 18, said that the program

helped him cope. Finishing a long, hard problem was “the best feeling in the

world,” Avdieiev said last fall from his apartment in Berlin. (He noted that

math had long been a passion of his; at age 4, he liked to add license plate

numbers.)

As the war began, he was making plans to

attend V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, which suffered extensive

damage from Russian missiles in March 2022. “All my plans were ruined,” he

said. He relocated on his own to continue his mathematical education; that he

might be required to serve in the military was also a factor in the decision.

This year he is at the University of Bonn and studying remotely at Karazin

University, pursuing two mathematics degrees.

Dmytro Antonovych, 18, of Chernivtsi, is

now at Minerva University in San Francisco, where he intends to study

mathematics and data science. He attended the meetings on Zoom, at least twice

weekly, from his dorm room at Ipswich School in the U.K. Antonovych found the

program meaningful, he said, because “it gave me a vision of how I could use my

knowledge in mathematics.” And he appreciated the advice on how to succeed in

mathematical research provided by Pavel Etingof, a mathematician at MIT and the

chief research adviser and a co-founder of PRIMES. One of the tips Antonovych

especially liked: “Listen to your heart. As in all important things in life,

what you want and what you dream about is the most essential.”

‘An Opera House for Math’

On a Wednesday afternoon last month in

Kyiv, the conference began in a fifth-floor lecture room with a view of the

city. During a special session dedicated to the opening of the center, an air-raid

alert sent the attendees, including several dignitaries, into the basement bomb

shelter. A City Council member in attendance arranged a meeting the following

day with the mayor, Vitali Klitschko, a former world boxing champion with a

doctorate in sports science. Klitschko pledged his support for the project.

“He said that his mission is to make Kyiv

so beautiful that people come back, because many people have left during the

war,” said Vlasenko, who attended the meeting along with a group representing

the center. She had described the center to the mayor as “an opera house for

math.”

The conference atmosphere was “total

excitement,” Vlasenko recalled. “One could feel it.” Every talk prompted so

many questions afterward — “we let all questions go until there were no more

questions,” she said — that every day the schedule ran two hours over. Even the

problem-solving sessions went late, fueled by the energy of the students.

“It was very inspiring to see how

first-year bachelor students are solving problems in advanced topics in

mathematics,” said Olha Kharchenko, 23, who is in the second year of a master’s

program at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany. The conference was her

first time back in Ukraine since the war started.

Most of Kharchenko’s family is still in the

Russian-occupied city of Kakhovka, where a major dam was destroyed in June. She

already had hopes of returning to Ukraine for her career; the new center makes

it feel feasible. Eventually, postdoctoral and long-term visiting positions

would allow Ukrainian mathematicians like her to split their time between the

ICMU and other institutions.

During the conference, Kharchenko also

began thinking about returning sooner rather than later, before starting her

doctorate. She felt an urgency “to be present in Kyiv,” she said, “to

understand what is happening there and to make my small impact to the education

in Ukraine.” Maybe she would teach undergraduate students or children — things

were changing in the country so fast, she said, it was difficult to foresee

what the situation would be a year or so from now.

“It’s just my plan,” Kharchenko said. “I

don’t know what will be there.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News