King Tut died long ago, but the debate about his tomb rages on

New York Times

last updated: Nov 10,2022

More than three millennia after Tutankhamen was buried in southern Egypt, and

a century after his tomb was discovered, Egyptologists are still squabbling

over whom the chamber was built for and what, if anything, lies beyond its

walls. The debate has become a global pastime.

At the center of the rumpus is confrontational

enthusiast Nicholas Reeves, 66, who shares a home near Oxford, England, with a

nameless house cat. In July 2015, Reeves, a former curator at the British

Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posited the tantalizing theory that

there were rooms hidden behind the northern and western walls in the

treasure-packed burial vault of Tutankhamen, otherwise known as King Tut.

It was long

presumed that the small burial chamber, constructed 3,300 years ago and known

to specialists as KV62, was originally intended as a private tomb for

Tutankhamen’s successor, Ay, until Tutankhamen died prematurely at 19. Reeves

proposed that the tomb was, in fact, merely an antechamber to a grander

sepulcher for Tutankhamen’s stepmother and predecessor, Nefertiti. What is

more, Reeves argued, behind the north wall was a corridor that might well lead

to Nefertiti’s unexplored funerary apartments, and perhaps to Nefertiti

herself.

The Egyptian government authorized radar surveys

using ground-penetrating radar that could detect and scan cavities underground.

At a news conference in Cairo in March 2016, Mamdouh Eldamaty, then Egypt’s

antiquities minister, showed the preliminary results of radar scans that

revealed anomalies beyond the decorated north and west walls of the tomb,

suggesting the presence of two empty spaces and organic or metal objects.

To much fanfare, he announced that there was an

“approximately 90 percent” chance that something — “another chamber, another

tomb” — was waiting beyond KV62. (Reeves said: “There was constant pressure

from the press for odds. My own response was 50–50 — radar will either reveal

there’s more to Tutankhamen’s tomb than we currently see, or it won’t.”)

Yet two years and two separate radar surveys later,

a new antiquities minister declared that there were neither blocked doorways

nor hidden rooms inside the tomb. Detailed results of the final scan were not

released for independent scrutiny. Nonetheless, the announcement prompted

National Geographic magazine to withdraw funding for Reeves’ project and a

prominent Egyptologist to say: “We should not pursue hallucination”.

Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s onetime chief antiquities

official and author of “King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb”, said: “I

completely disagree with this theory. There is no way in ancient Egypt that any

king would block the tomb of someone else. This would be completely against all

their beliefs. It is impossible!”

Reeves countered by pointing out that every

successor king was responsible for closing the tomb of his predecessor, as the

mythical Horus buried his father, Osiris. “This is even demonstrated in what we

currently see on the burial chamber’s north wall, as labeled Ay burying

Tutankhamen,” Reeves said.

Kara Cooney, a professor of Egyptian art and

architecture at the University of California, Los Angeles, noted the fraught

scholarly terrain.

“Nick’s work is evidence-based and carefully

researched,” she said. “But few Egyptologists will say it on record because

they are all afraid of losing their access to tombs and excavation concessions.

Or they are just plain jerks.”

Despite the setback, Reeves soldiered on. In “The

Complete Tutankhamun: 100 Years of Discovery”, a freshly revised edition of his

1990 book to be published in January, he draws on data provided by thermal

imaging, laser scanning, mold-growth mapping, and inscriptional analysis to

support his fiercely debated scholarship. The provocative new evidence has

bolstered his belief that Tutankhamen was given a hasty burial in the front

hallway of the tomb of Nefertiti.

“Much of what Tutankhamen took to the grave had

nothing to do with him,” said Reeves, who spoke by video from his home office.

He maintained that King Tut had inherited a suite of lavish burial equipment

that had then been repurposed to accompany him into the afterlife, including

his famous gold death mask.

The father of Tutankhamen was Akhenaten, the

so-called heretic king whose reign was characterized by social, political, and

religious upheaval. The 18th-dynasty pharaoh rejected Amun, Osiris, and Egypt’s

traditional gods in favor of a single disembodied creator-essence, Aten, or the

sun disc. In the space of a generation, Akhenaten had created a city from

scratch at Al-Amarna for his new god, and prepared royal tombs for himself, his

children, and his wives, including Nefertiti.

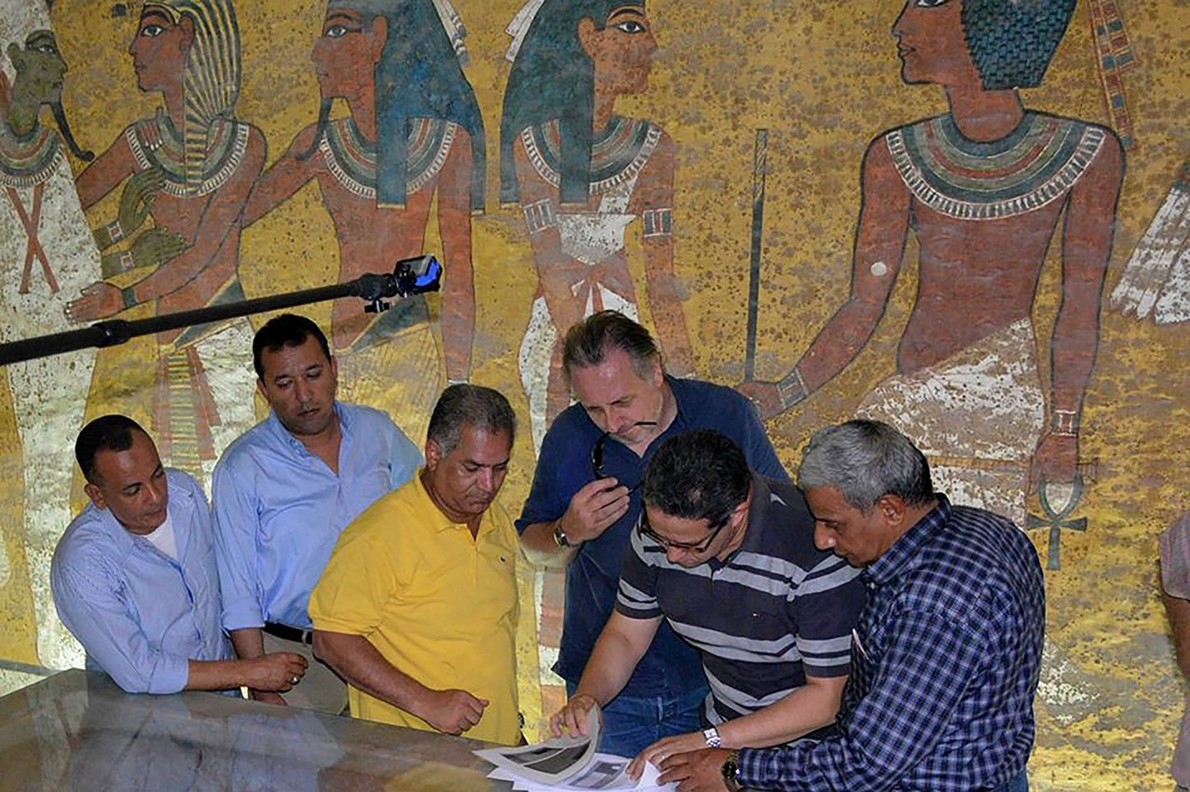

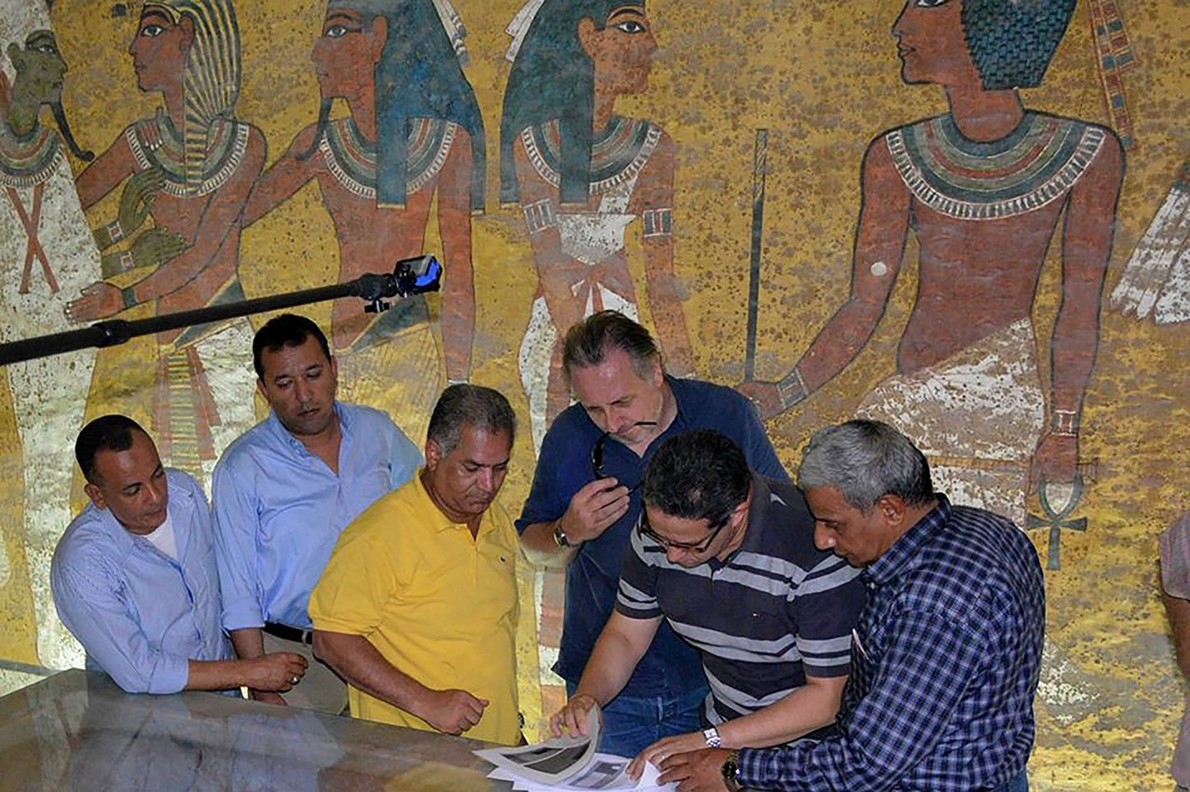

Nicholas Reeves (third from right) evaluates documents inside the tomb of King Tutankhamen in Luxor, Egypt. (Photo: NYTimes)

After Akhenaten came an obscure pharaoh named

Smenkhkare, whom Tutankhamen succeeded directly. Reeves has long held that

Smenkhkare and Nefertiti were the same person, and that Akhenaten’s queen simply

changed her name, first to Neferneferuaten, during a period of rule with her

husband, and then to Smenkhkare following his death, navigating a period of

sole, independent rule. To the boy-king would fall the burial of this rare

female pharaoh.

During King Tut’s decadelong reign, he appeared to

have been largely occupied with rectifying the chaos bequeathed to him by his

old man. But it would not be enough: Shortly after his death in 1,323 BC, a new

dynasty chiseled his tarnished name into dust.

Pyramid scheme

Reeves has conducted research directly in the tomb on several occasions

over the years. He came to his theory about Tutankhamen in 2014 after examining

high-resolution color photographs of the tomb, which were published online by

Factum Arte, a company based in Madrid and Bologna, Italy, that specializes in

art recording and replication. The images showed lines beneath the plastered

surfaces of painted walls, suggesting uncharted doorways. He speculated that

one doorway — in the west — opened into a Tutankhamen-era storeroom, and that

another, which aligns with both sides of the entrance chamber, opened to a

hallway continuing along the same axis in form and orientation reminiscent of a

more extensive queen’s corridor tomb.

“I saw early on,

from the face of the north wall subject, that the larger tomb could only belong

to Nefertiti,” Reeves said. “I also suggested, based on evidence from

elsewhere, that the perceived storage chamber to the west of the burial chamber

might have been adapted into a funerary suite for other missing members of the

Amarna royal family.”

To support his

radical reassessment, Reeves pointed to a pair of cartouches — ovals or oblongs

enclosing a group of hieroglyphs — and a curious misspelling painted on the

tomb’s north wall. The figure beneath the first cartouche is named as

Tutankhamen’s Pharaonic successor, Ay, and is shown officiating at the young

king’s burial carrying out the “opening the mouth” ceremony, a funerary ritual

to restore the deceased’s senses — the ability to speak, touch, see, smell, and

hear. The key, Reeves said, is that both of the Ay cartouches show clear

evidence of having been changed from their originals — the birth and throne

names of Tutankhamen.

Reeves suggested

that the cartouches had originally showed Tut burying his predecessor, and that

the cartouches — and hence the tomb — were put to new use.

“If you inspect

the birth name cartouche closely, you see clear, underlying traces of a reed

leaf,” he said in an email. “Not by chance, this hieroglyph is the first

character of the divine component of Tutankhamen’s name, ‘-amun,’ in all

standard writings.”

Beneath Ay’s

throne name may be discerned a rare, variant writing of Tutankhamen’s throne

name, “Nebkheperure”, employing three scarab beetles. This is a variant whose

lazy adaptation provides the only feasible explanation for the strangely

misspelled three-scarab version of the Ay throne name “Kheperkheperure” that

now stands there, Reeves said.

He deduced that

the scene had originally depicted not Ay presiding over the interment of

Tutankhamen, but Tutankhamen presiding over the burial of Nefertiti. There are

two visual clinchers, he said. The first is the “rounded, childlike, double

underchin” of the Ay figure, a feature not present in any image currently

recognizable as him, implying that the original painting of the king must have

been of the chubby, young Tutankhamen. The second is the facial contours of the

mummified recipient — until now presumed to be Tutankhamen — whose lips, narrow

neck and distinctive nasal bridge are a “perfect match” for the profile of the

painted limestone bust of Nefertiti on display in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

“There would

have been no reason to include a depiction of this predecessor’s burial in

Tutankhamen’s own tomb,” Reeves said. “In fact, the presence of this scene

identifies Tutankhamen’s tomb as the burial place of that predecessor, and that

it was within her outer chambers that the young king had, in extremis, been

buried.”

Rita Lucarelli, an Egyptology curator at the University of California,

Berkeley, said she had been following Reeves’ old and new claims with interest.

“If he is right,

it would be an amazing discovery because the tomb of Nefertiti would be intact,

too,” she said. “But maybe even if there is a tomb there, it’s not that of

Nefertiti, rather of another individual related to Tut. We simply cannot know

it unless we dig through the bedrock.”

The problem,

Lucarelli said, is finding a way to drill through the decorated north wall

without destroying it. “This is also why other archaeologists do not sympathize

with this theory,” she said.

Reeves’

unsympathetic colleagues are legion.

“Nick is

flogging a dead horse in his theories,” Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist at the

University of Bristol, said. “He has provided no clear proof that the

cartouches have been altered, and his iconographic arguments as to the faces on

the wall have been rejected by pretty well every other Egyptologist I know of

who is qualified to take a view.”

The politics of

heritage

At least part of the backlash against Reeves’ ideas can be traced to

the politics of heritage. The narrative that Tutankhamen’s tomb was unearthed

by heroic English archaeologist Howard Carter has long been openly challenged

by Egyptians, who took the discovery as a rallying cry to end 1920s British

rule and establish a modern Egyptian identity. Among Egyptologists today, the

hot topics include the decolonization of the field and more inclusive and

equitable accounts of Egyptian team members involved in archaeological

excavations.

“Sure, some in

Egypt take a different view from me, which is easy enough to understand,”

Reeves said. A weary expression spread over his face. “Archaeologists in the UK

would, I am sure, look askance at some foreigner sounding off on who might be

buried in Westminster Abbey. But my sole interest as an academic Egyptologist,

my intellectual responsibility, is to seek out the evidence and report honestly

and as objectively as possible on what I find.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_509089081')

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_552628228')

Read More

It’s one of Ukraine’s fiercest allies. But an election could change that

Hemingway’s letter about surviving two plane crashes sold for over $237k

News and notes about science

More than three millennia after Tutankhamen was buried in southern Egypt, and

a century after his tomb was discovered, Egyptologists are still squabbling

over whom the chamber was built for and what, if anything, lies beyond its

walls. The debate has become a global pastime.

At the center of the rumpus is confrontational enthusiast Nicholas Reeves, 66, who shares a home near Oxford, England, with a nameless house cat. In July 2015, Reeves, a former curator at the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posited the tantalizing theory that there were rooms hidden behind the northern and western walls in the treasure-packed burial vault of Tutankhamen, otherwise known as King Tut.

It was long presumed that the small burial chamber, constructed 3,300 years ago and known to specialists as KV62, was originally intended as a private tomb for Tutankhamen’s successor, Ay, until Tutankhamen died prematurely at 19. Reeves proposed that the tomb was, in fact, merely an antechamber to a grander sepulcher for Tutankhamen’s stepmother and predecessor, Nefertiti. What is more, Reeves argued, behind the north wall was a corridor that might well lead to Nefertiti’s unexplored funerary apartments, and perhaps to Nefertiti herself.

The Egyptian government authorized radar surveys using ground-penetrating radar that could detect and scan cavities underground. At a news conference in Cairo in March 2016, Mamdouh Eldamaty, then Egypt’s antiquities minister, showed the preliminary results of radar scans that revealed anomalies beyond the decorated north and west walls of the tomb, suggesting the presence of two empty spaces and organic or metal objects.

To much fanfare, he announced that there was an “approximately 90 percent” chance that something — “another chamber, another tomb” — was waiting beyond KV62. (Reeves said: “There was constant pressure from the press for odds. My own response was 50–50 — radar will either reveal there’s more to Tutankhamen’s tomb than we currently see, or it won’t.”)

Yet two years and two separate radar surveys later, a new antiquities minister declared that there were neither blocked doorways nor hidden rooms inside the tomb. Detailed results of the final scan were not released for independent scrutiny. Nonetheless, the announcement prompted National Geographic magazine to withdraw funding for Reeves’ project and a prominent Egyptologist to say: “We should not pursue hallucination”.

Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s onetime chief antiquities official and author of “King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb”, said: “I completely disagree with this theory. There is no way in ancient Egypt that any king would block the tomb of someone else. This would be completely against all their beliefs. It is impossible!”

Reeves countered by pointing out that every successor king was responsible for closing the tomb of his predecessor, as the mythical Horus buried his father, Osiris. “This is even demonstrated in what we currently see on the burial chamber’s north wall, as labeled Ay burying Tutankhamen,” Reeves said.

Kara Cooney, a professor of Egyptian art and architecture at the University of California, Los Angeles, noted the fraught scholarly terrain.

“Nick’s work is evidence-based and carefully researched,” she said. “But few Egyptologists will say it on record because they are all afraid of losing their access to tombs and excavation concessions. Or they are just plain jerks.”

Despite the setback, Reeves soldiered on. In “The Complete Tutankhamun: 100 Years of Discovery”, a freshly revised edition of his 1990 book to be published in January, he draws on data provided by thermal imaging, laser scanning, mold-growth mapping, and inscriptional analysis to support his fiercely debated scholarship. The provocative new evidence has bolstered his belief that Tutankhamen was given a hasty burial in the front hallway of the tomb of Nefertiti.

“Much of what Tutankhamen took to the grave had nothing to do with him,” said Reeves, who spoke by video from his home office. He maintained that King Tut had inherited a suite of lavish burial equipment that had then been repurposed to accompany him into the afterlife, including his famous gold death mask.

The father of Tutankhamen was Akhenaten, the so-called heretic king whose reign was characterized by social, political, and religious upheaval. The 18th-dynasty pharaoh rejected Amun, Osiris, and Egypt’s traditional gods in favor of a single disembodied creator-essence, Aten, or the sun disc. In the space of a generation, Akhenaten had created a city from scratch at Al-Amarna for his new god, and prepared royal tombs for himself, his children, and his wives, including Nefertiti.

Nicholas Reeves (third from right) evaluates documents inside the tomb of King Tutankhamen in Luxor, Egypt. (Photo: NYTimes)

After Akhenaten came an obscure pharaoh named Smenkhkare, whom Tutankhamen succeeded directly. Reeves has long held that Smenkhkare and Nefertiti were the same person, and that Akhenaten’s queen simply changed her name, first to Neferneferuaten, during a period of rule with her husband, and then to Smenkhkare following his death, navigating a period of sole, independent rule. To the boy-king would fall the burial of this rare female pharaoh.

During King Tut’s decadelong reign, he appeared to have been largely occupied with rectifying the chaos bequeathed to him by his old man. But it would not be enough: Shortly after his death in 1,323 BC, a new dynasty chiseled his tarnished name into dust.

Pyramid scheme

Reeves has conducted research directly in the tomb on several occasions over the years. He came to his theory about Tutankhamen in 2014 after examining high-resolution color photographs of the tomb, which were published online by Factum Arte, a company based in Madrid and Bologna, Italy, that specializes in art recording and replication. The images showed lines beneath the plastered surfaces of painted walls, suggesting uncharted doorways. He speculated that one doorway — in the west — opened into a Tutankhamen-era storeroom, and that another, which aligns with both sides of the entrance chamber, opened to a hallway continuing along the same axis in form and orientation reminiscent of a more extensive queen’s corridor tomb.

“I saw early on, from the face of the north wall subject, that the larger tomb could only belong to Nefertiti,” Reeves said. “I also suggested, based on evidence from elsewhere, that the perceived storage chamber to the west of the burial chamber might have been adapted into a funerary suite for other missing members of the Amarna royal family.”

To support his radical reassessment, Reeves pointed to a pair of cartouches — ovals or oblongs enclosing a group of hieroglyphs — and a curious misspelling painted on the tomb’s north wall. The figure beneath the first cartouche is named as Tutankhamen’s Pharaonic successor, Ay, and is shown officiating at the young king’s burial carrying out the “opening the mouth” ceremony, a funerary ritual to restore the deceased’s senses — the ability to speak, touch, see, smell, and hear. The key, Reeves said, is that both of the Ay cartouches show clear evidence of having been changed from their originals — the birth and throne names of Tutankhamen.

Reeves suggested that the cartouches had originally showed Tut burying his predecessor, and that the cartouches — and hence the tomb — were put to new use.

“If you inspect the birth name cartouche closely, you see clear, underlying traces of a reed leaf,” he said in an email. “Not by chance, this hieroglyph is the first character of the divine component of Tutankhamen’s name, ‘-amun,’ in all standard writings.”

Beneath Ay’s throne name may be discerned a rare, variant writing of Tutankhamen’s throne name, “Nebkheperure”, employing three scarab beetles. This is a variant whose lazy adaptation provides the only feasible explanation for the strangely misspelled three-scarab version of the Ay throne name “Kheperkheperure” that now stands there, Reeves said.

He deduced that the scene had originally depicted not Ay presiding over the interment of Tutankhamen, but Tutankhamen presiding over the burial of Nefertiti. There are two visual clinchers, he said. The first is the “rounded, childlike, double underchin” of the Ay figure, a feature not present in any image currently recognizable as him, implying that the original painting of the king must have been of the chubby, young Tutankhamen. The second is the facial contours of the mummified recipient — until now presumed to be Tutankhamen — whose lips, narrow neck and distinctive nasal bridge are a “perfect match” for the profile of the painted limestone bust of Nefertiti on display in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

“There would have been no reason to include a depiction of this predecessor’s burial in Tutankhamen’s own tomb,” Reeves said. “In fact, the presence of this scene identifies Tutankhamen’s tomb as the burial place of that predecessor, and that it was within her outer chambers that the young king had, in extremis, been buried.”

Rita Lucarelli, an Egyptology curator at the University of California, Berkeley, said she had been following Reeves’ old and new claims with interest.

“If he is right, it would be an amazing discovery because the tomb of Nefertiti would be intact, too,” she said. “But maybe even if there is a tomb there, it’s not that of Nefertiti, rather of another individual related to Tut. We simply cannot know it unless we dig through the bedrock.”

The problem, Lucarelli said, is finding a way to drill through the decorated north wall without destroying it. “This is also why other archaeologists do not sympathize with this theory,” she said.

Reeves’ unsympathetic colleagues are legion.

“Nick is flogging a dead horse in his theories,” Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist at the University of Bristol, said. “He has provided no clear proof that the cartouches have been altered, and his iconographic arguments as to the faces on the wall have been rejected by pretty well every other Egyptologist I know of who is qualified to take a view.”

The politics of heritage

At least part of the backlash against Reeves’ ideas can be traced to the politics of heritage. The narrative that Tutankhamen’s tomb was unearthed by heroic English archaeologist Howard Carter has long been openly challenged by Egyptians, who took the discovery as a rallying cry to end 1920s British rule and establish a modern Egyptian identity. Among Egyptologists today, the hot topics include the decolonization of the field and more inclusive and equitable accounts of Egyptian team members involved in archaeological excavations.

“Sure, some in Egypt take a different view from me, which is easy enough to understand,” Reeves said. A weary expression spread over his face. “Archaeologists in the UK would, I am sure, look askance at some foreigner sounding off on who might be buried in Westminster Abbey. But my sole interest as an academic Egyptologist, my intellectual responsibility, is to seek out the evidence and report honestly and as objectively as possible on what I find.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News

At the center of the rumpus is confrontational enthusiast Nicholas Reeves, 66, who shares a home near Oxford, England, with a nameless house cat. In July 2015, Reeves, a former curator at the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posited the tantalizing theory that there were rooms hidden behind the northern and western walls in the treasure-packed burial vault of Tutankhamen, otherwise known as King Tut.

It was long presumed that the small burial chamber, constructed 3,300 years ago and known to specialists as KV62, was originally intended as a private tomb for Tutankhamen’s successor, Ay, until Tutankhamen died prematurely at 19. Reeves proposed that the tomb was, in fact, merely an antechamber to a grander sepulcher for Tutankhamen’s stepmother and predecessor, Nefertiti. What is more, Reeves argued, behind the north wall was a corridor that might well lead to Nefertiti’s unexplored funerary apartments, and perhaps to Nefertiti herself.

The Egyptian government authorized radar surveys using ground-penetrating radar that could detect and scan cavities underground. At a news conference in Cairo in March 2016, Mamdouh Eldamaty, then Egypt’s antiquities minister, showed the preliminary results of radar scans that revealed anomalies beyond the decorated north and west walls of the tomb, suggesting the presence of two empty spaces and organic or metal objects.

To much fanfare, he announced that there was an “approximately 90 percent” chance that something — “another chamber, another tomb” — was waiting beyond KV62. (Reeves said: “There was constant pressure from the press for odds. My own response was 50–50 — radar will either reveal there’s more to Tutankhamen’s tomb than we currently see, or it won’t.”)

Yet two years and two separate radar surveys later, a new antiquities minister declared that there were neither blocked doorways nor hidden rooms inside the tomb. Detailed results of the final scan were not released for independent scrutiny. Nonetheless, the announcement prompted National Geographic magazine to withdraw funding for Reeves’ project and a prominent Egyptologist to say: “We should not pursue hallucination”.

Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s onetime chief antiquities official and author of “King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb”, said: “I completely disagree with this theory. There is no way in ancient Egypt that any king would block the tomb of someone else. This would be completely against all their beliefs. It is impossible!”

Reeves countered by pointing out that every successor king was responsible for closing the tomb of his predecessor, as the mythical Horus buried his father, Osiris. “This is even demonstrated in what we currently see on the burial chamber’s north wall, as labeled Ay burying Tutankhamen,” Reeves said.

Kara Cooney, a professor of Egyptian art and architecture at the University of California, Los Angeles, noted the fraught scholarly terrain.

“Nick’s work is evidence-based and carefully researched,” she said. “But few Egyptologists will say it on record because they are all afraid of losing their access to tombs and excavation concessions. Or they are just plain jerks.”

Despite the setback, Reeves soldiered on. In “The Complete Tutankhamun: 100 Years of Discovery”, a freshly revised edition of his 1990 book to be published in January, he draws on data provided by thermal imaging, laser scanning, mold-growth mapping, and inscriptional analysis to support his fiercely debated scholarship. The provocative new evidence has bolstered his belief that Tutankhamen was given a hasty burial in the front hallway of the tomb of Nefertiti.

“Much of what Tutankhamen took to the grave had nothing to do with him,” said Reeves, who spoke by video from his home office. He maintained that King Tut had inherited a suite of lavish burial equipment that had then been repurposed to accompany him into the afterlife, including his famous gold death mask.

The father of Tutankhamen was Akhenaten, the so-called heretic king whose reign was characterized by social, political, and religious upheaval. The 18th-dynasty pharaoh rejected Amun, Osiris, and Egypt’s traditional gods in favor of a single disembodied creator-essence, Aten, or the sun disc. In the space of a generation, Akhenaten had created a city from scratch at Al-Amarna for his new god, and prepared royal tombs for himself, his children, and his wives, including Nefertiti.

Nicholas Reeves (third from right) evaluates documents inside the tomb of King Tutankhamen in Luxor, Egypt. (Photo: NYTimes)

After Akhenaten came an obscure pharaoh named Smenkhkare, whom Tutankhamen succeeded directly. Reeves has long held that Smenkhkare and Nefertiti were the same person, and that Akhenaten’s queen simply changed her name, first to Neferneferuaten, during a period of rule with her husband, and then to Smenkhkare following his death, navigating a period of sole, independent rule. To the boy-king would fall the burial of this rare female pharaoh.

During King Tut’s decadelong reign, he appeared to have been largely occupied with rectifying the chaos bequeathed to him by his old man. But it would not be enough: Shortly after his death in 1,323 BC, a new dynasty chiseled his tarnished name into dust.

Pyramid scheme

Reeves has conducted research directly in the tomb on several occasions over the years. He came to his theory about Tutankhamen in 2014 after examining high-resolution color photographs of the tomb, which were published online by Factum Arte, a company based in Madrid and Bologna, Italy, that specializes in art recording and replication. The images showed lines beneath the plastered surfaces of painted walls, suggesting uncharted doorways. He speculated that one doorway — in the west — opened into a Tutankhamen-era storeroom, and that another, which aligns with both sides of the entrance chamber, opened to a hallway continuing along the same axis in form and orientation reminiscent of a more extensive queen’s corridor tomb.

“I saw early on, from the face of the north wall subject, that the larger tomb could only belong to Nefertiti,” Reeves said. “I also suggested, based on evidence from elsewhere, that the perceived storage chamber to the west of the burial chamber might have been adapted into a funerary suite for other missing members of the Amarna royal family.”

To support his radical reassessment, Reeves pointed to a pair of cartouches — ovals or oblongs enclosing a group of hieroglyphs — and a curious misspelling painted on the tomb’s north wall. The figure beneath the first cartouche is named as Tutankhamen’s Pharaonic successor, Ay, and is shown officiating at the young king’s burial carrying out the “opening the mouth” ceremony, a funerary ritual to restore the deceased’s senses — the ability to speak, touch, see, smell, and hear. The key, Reeves said, is that both of the Ay cartouches show clear evidence of having been changed from their originals — the birth and throne names of Tutankhamen.

Reeves suggested that the cartouches had originally showed Tut burying his predecessor, and that the cartouches — and hence the tomb — were put to new use.

“If you inspect the birth name cartouche closely, you see clear, underlying traces of a reed leaf,” he said in an email. “Not by chance, this hieroglyph is the first character of the divine component of Tutankhamen’s name, ‘-amun,’ in all standard writings.”

Beneath Ay’s throne name may be discerned a rare, variant writing of Tutankhamen’s throne name, “Nebkheperure”, employing three scarab beetles. This is a variant whose lazy adaptation provides the only feasible explanation for the strangely misspelled three-scarab version of the Ay throne name “Kheperkheperure” that now stands there, Reeves said.

He deduced that the scene had originally depicted not Ay presiding over the interment of Tutankhamen, but Tutankhamen presiding over the burial of Nefertiti. There are two visual clinchers, he said. The first is the “rounded, childlike, double underchin” of the Ay figure, a feature not present in any image currently recognizable as him, implying that the original painting of the king must have been of the chubby, young Tutankhamen. The second is the facial contours of the mummified recipient — until now presumed to be Tutankhamen — whose lips, narrow neck and distinctive nasal bridge are a “perfect match” for the profile of the painted limestone bust of Nefertiti on display in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

“There would have been no reason to include a depiction of this predecessor’s burial in Tutankhamen’s own tomb,” Reeves said. “In fact, the presence of this scene identifies Tutankhamen’s tomb as the burial place of that predecessor, and that it was within her outer chambers that the young king had, in extremis, been buried.”

Rita Lucarelli, an Egyptology curator at the University of California, Berkeley, said she had been following Reeves’ old and new claims with interest.

“If he is right, it would be an amazing discovery because the tomb of Nefertiti would be intact, too,” she said. “But maybe even if there is a tomb there, it’s not that of Nefertiti, rather of another individual related to Tut. We simply cannot know it unless we dig through the bedrock.”

The problem, Lucarelli said, is finding a way to drill through the decorated north wall without destroying it. “This is also why other archaeologists do not sympathize with this theory,” she said.

Reeves’ unsympathetic colleagues are legion.

“Nick is flogging a dead horse in his theories,” Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist at the University of Bristol, said. “He has provided no clear proof that the cartouches have been altered, and his iconographic arguments as to the faces on the wall have been rejected by pretty well every other Egyptologist I know of who is qualified to take a view.”

The politics of heritage

At least part of the backlash against Reeves’ ideas can be traced to the politics of heritage. The narrative that Tutankhamen’s tomb was unearthed by heroic English archaeologist Howard Carter has long been openly challenged by Egyptians, who took the discovery as a rallying cry to end 1920s British rule and establish a modern Egyptian identity. Among Egyptologists today, the hot topics include the decolonization of the field and more inclusive and equitable accounts of Egyptian team members involved in archaeological excavations.

“Sure, some in Egypt take a different view from me, which is easy enough to understand,” Reeves said. A weary expression spread over his face. “Archaeologists in the UK would, I am sure, look askance at some foreigner sounding off on who might be buried in Westminster Abbey. But my sole interest as an academic Egyptologist, my intellectual responsibility, is to seek out the evidence and report honestly and as objectively as possible on what I find.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News