Paleontologists last week unveiled the fossilized bones of

one of the strangest whales in history. The 39-million-year-old leviathan,

called Perucetus, may have weighed about 200 tons — as much as a blue whale, by

far the heaviest animal known, until now.

اضافة اعلان

Although blue whales are sleek, fast-swimming divers,

Perucetus was a very different beast. The researchers suspect that it drifted

lazily through shallow coastal waters like a mammoth manatee, propelling its

sausagelike body with a paddle-shaped tail.

Some experts cautioned that more bones would have to be

discovered before a firm estimate of Perucetus’s weight could be made. But they

all agreed that the bizarre find would change the way paleontologists saw the

evolution of whales from land mammals.

“This is a weird and stupendous fossil, for sure,” said

Nicholas Pyenson, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of

Natural History, who was not involved in the study. “It’s clear from this

discovery that there are so many other ways of being a whale that we have not

yet discovered.”

Mario Urbina, a paleontologist at the Museum of Natural

History at the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru, first set eyes

on Perucetus in 2010. He was walking across the Atacama Desert in southern Peru

when he noticed a rocky bump bulging out of the sand. When he and his

colleagues finished digging it out, the lump proved to be a gigantic vertebra.

Digging further, the researchers found 13 vertebrae in

total, along with four ribs and part of a pelvis. Except for the pelvis, all

the fossils were remarkably dense and strangely thickened, making it hard to

figure out what kind of animal they belonged to.

Only the pelvis revealed exactly what the scientists had

found. Unlike the other bones, the pelvis was small and delicately formed. It

had crests and other distinctive features that revealed it to be a whale’s — in

particular, from an early branch of the evolutionary tree of whales.

In a photo provided by Alberto Gennari shows, an

excavation of the Perucetus fossils in Ica Province, Peru.

In a photo provided by Alberto Gennari shows, an

excavation of the Perucetus fossils in Ica Province, Peru.

Whales evolved from dog-size land mammals about 50 million

years ago. Some of the earliest species evolved short limbs and most likely led

a seallike existence, hunting for fish and then hauling themselves onto the

shore to reproduce.

Those early whales disappeared after a few million years.

They were replaced by a group of entirely aquatic whales called basilosaurids.

These slinky beasts could grow as long as a school bus but retained vestiges of

their life on land — including tiny hind legs, complete with toes.

Basilosaurids dominated the oceans until about 35 million

years ago. As they became extinct, another group of whales emerged, giving rise

to the ancestors of living whales.

Today’s biggest whales, including blue whales and fin

whales, reached their gargantuan sizes only in the past few million years.

Shifts in ocean currents supported vast populations of krill and other

invertebrates near the poles. The whales could grow immense by scooping up

these prey on lunging dives.

The pelvis of Perucetus revealed it to be a basilosaurid,

but the whale had evolved into a basilosaurid unlike any found before. Eli

Amson, an expert on bone tissue at the State Museum of Natural History in

Stuttgart, Germany, found that its ribs and spine had extra layers of outer

bone, giving them bloated shapes.

A typical bone is full of pores, which make it lighter

without sacrificing strength. Amson observed that the bones of Perucetus were

solid throughout. The fossil is so hard in parts that it would be impossible to

drive a nail into it with a hammer.

“It would make nothing but sparks,” he said.

Amson and his colleagues made 3D scans of the fossil bones

to reconstruct the whale’s full skeleton. They compared Perucetus to other

basilosaurids that have been preserved from head to tail.

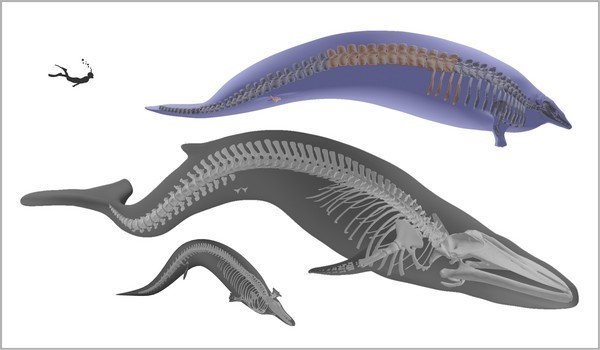

In a photo provided by Florent Goussard; Imaging

and Analysis Centre at the Natural History Museum in London; Marco Merella and

Rebecca Bennion shows, a comparison of Perucetus, top, with a blue whale,

middle, and another, smaller basilosaurid, Cynthiacetus peruvianus.

In a photo provided by Florent Goussard; Imaging

and Analysis Centre at the Natural History Museum in London; Marco Merella and

Rebecca Bennion shows, a comparison of Perucetus, top, with a blue whale,

middle, and another, smaller basilosaurid, Cynthiacetus peruvianus.

If the rest of Perucetus were a denser, thickened version of

these whales, its complete skeleton would weigh between 5.8 and 8.3 tons. That

would mean Perucetus had the heaviest skeleton of any mammal — bones that were

twice as heavy as a blue whale’s.

That bulky skeleton also suggests that Perucetus had a

thick, barrellike body. Even though Perucetus was only about two-thirds the

length of a blue whale, Amson and his colleagues suspect that it weighed about

the same.

“It’s definitely in the blue whale ballpark,” Amson said.

Pyenson thought it was premature to make such an estimate.

“Until we find the rest of the skeleton, I think we should shelve the

heavyweight-contender issue,” he said.

But Hans Thewissen, a paleontologist at Northeast Ohio

Medical University, who was not involved in the study, said the estimate was

reasonable. “I agree with the excitement around the weight,” he said.

The fossil suggests that Perucetus reached such a big size

without feeding as blue whales do. The analysis of its bones suggests it lived

more like a gargantuan manatee.

Manatees graze on sea grass on the ocean floor. Their lungs

are full of air, and their guts produce gas as they ferment their food. To stay

underwater, manatees have evolved dense bones as ballast.

The structure of Perucetus’s spine is similar to that of a

manatee. Amson envisioned the whale swimming in a manatee style, slowly raising

and lowering its tail.

Based on the rocks where the fossils were found, Amson and

his colleagues suspect that Perucetus moved slowly through coastal waters no

deeper than 150 feet. But how they fueled their giant bodies is still a

mystery.

Amson said it was possible that Perucetus also fed on sea

grass, but that would make it the first herbivorous whale known to science. “We

deem it unlikely, but who knows?” he said.

Amson even imagines Perucetus possibly living as a

scavenger, picking over carcasses.

By contrast, Thewissen favored the idea that these whales

scooped up mud from the sea floor to eat the worms and shellfish it contained —

something that gray whales do today.

The head of Perucetus would have adaptations for whichever

way of life it pursued. “I would love to see the skull of this guy,” Thewissen

said.

However it made a living, Perucetus is proof that whales did

not have to wait until recently to get huge. “The most important message is not

that we can enter the Guinness Book of World Records,” Amson said. “It’s that

there’s another path to gigantism.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News