The Chittenango Creek, which runs north for

about 48 twisting kilometers in central

New York, has few distinguishing

markers: The stream is generally only a couple of feet deep, and the towns it

passes through are similarly small and overlooked.

اضافة اعلان

One exception is

found a couple kilometers from the source of the creek, where the riverbed

flattens out and drops 50m over a series of limestone cliffs that are segmented

into ledges and still smaller rock shelves. The fractal qualities are magnified

by the foaming water that tumbles in thin layers down the cliffs. On some

mornings, sunlight from the southeast illuminates the mist, and the whole area

glows.

Around this time

on a recent Thursday, a dozen people clustered on one side of the falls, along

two ledges that were blanketed in snakeroot, yellow jewelweed, spotted Joe-Pye

weed and pale swallowwort. Here, in an area about the size of a living room, is

the only known habitat of a small, critically endangered invertebrate with a

marbled spiral shell: the Chittenango ovate amber snail.

A thousand

species of land snail worldwide are known to be at risk of extinction. Most

have very specific needs and a limited geological range, so scientists have

been studying their populations to understand how changes in the environment

could affect biodiversity more broadly. “Land snails are apt to be the real

canaries in the coal mine for these sorts of changes,” said Rebecca Rundell, a

biologist at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

Rundell is conducting such research on endangered

land snails in the Republic of Palau, and similar projects are underway in such

far-flung places as Hawaii and Bermuda. But the same issues are at play in her

backyard, with the “Chits,” which can only flourish in nearly 100 percent

humidity and the shade of deciduous forests. “The conservation status of our

local snail is emblematic of what is happening to land snails globally,” she

said.

And so Rundell’s

team, with volunteers and employees from the New York Department of

Environmental Conservation, gathered on the side of the waterfall, their feet

and knees planted cautiously but firmly on rocks, and sifted gently through the

dirt and roots. Their goal: to figure out how many of these snails remain in

the wild without crushing any in the process.

Cody Gilbertson,

a biologist in Rundell’s lab who has helped lead research on Chits for the past

decade, was up near the top of the falls watching over five mature snails that

she had raised in captivity and was preparing to release. “Snailsitting,” she

called it.

When survey

efforts first started, wild Chits could be found all over the spray zone of the

waterfall. But those numbers dropped steadily over the years. A rockslide in

2009 took out a large chunk of the population, and heavy rainfall damaged the

habitat periodically. In 2010, the number of wild Chits was around 1,000; in

2015 it was around 400; this year, after five preliminary surveys earlier in

the summer, Gilbertson said, “the numbers are quite dismal” — in the double

digits.

The day before the survey, Gilbertson sat in a

white-walled lab in Syracuse, New York, counting out baby Chits, each smaller

than a sesame seed, that speckled the inside of plastic deli containers. Some

150 mature snails and 200 juveniles had been raised in the lab, and one of the

babies had seemingly disappeared.

“It’s very

tedious,” Gilbertson said, handing the container to Alyssa Whitbread, a researcher

who has been helping study Chits since 2017. Using a small, flat-tipped

paintbrush, Whitbread started to comb through the leaves that lined the

container. “Sometimes they like to hide in cracks that you don’t think to look

in,” she said.

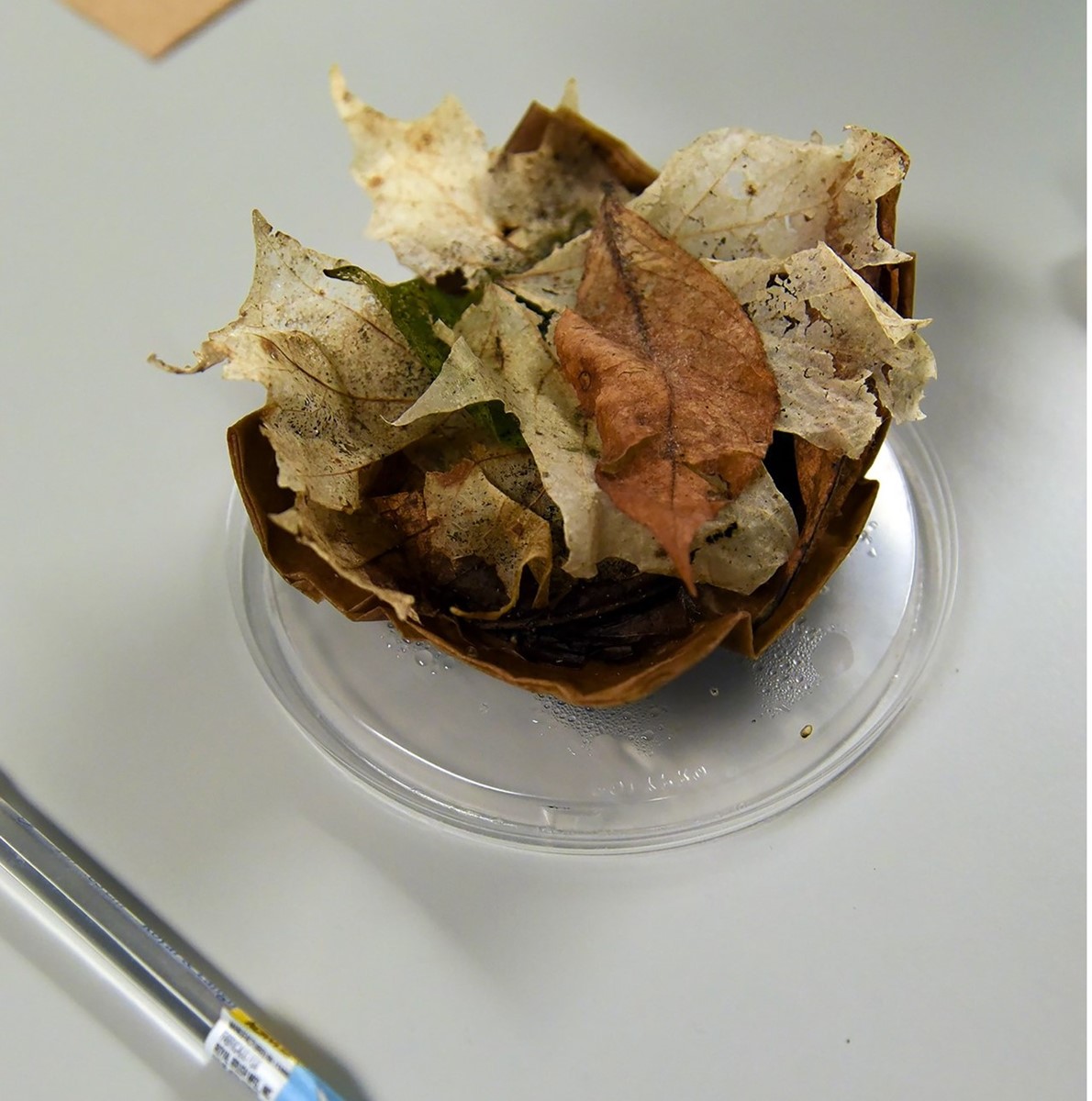

A “leaf lasagna” prepared for the terrarium of captive Chittenango ovate amber snails at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York, on August 26, 2022.

A “leaf lasagna” prepared for the terrarium of captive Chittenango ovate amber snails at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York, on August 26, 2022.

Chits are born

with their shells, which start out pearly white and darken over time. Hard

enough to see when alive, they often disintegrate after death. Counting the

captive animals — which Whitbread, Gilbertson, and Marlene Goldstein, an

undergraduate at SUNY, do each week — often takes hours. But the snail

population in this lab and the wild one at the Chittenango Falls are the only

two in the world. Lose track of one snail, and you’ve lost track of one of the

last Chits on Earth.

Still,

existential rumination can go on only so long. “At a certain point, we just

have to move on,” Gilbertson said, after Whitbread failed to find the itinerant

snail.

Most of

Gilbertson’s scientific career has been dedicated to figuring out how to keep a

Chit population alive in captivity. An effort in the late 1990s failed, and a

decade later, when Gilbertson first collected a handful of adults and brought

them into the lab, they refused to eat anything. The animals slowly died, as

Gilbertson “frantically grabbed stuff from the falls” to try to feed them, she

said.

Then one day,

miraculously, a cherry leaf worked.

Maintaining a

captive population of Chits can theoretically bolster the existing population

of wild snails, serve as a last-ditch defense against their extinction and,

perhaps eventually, be the source for a new wild population in a different

waterfall spray zone. But Gilbertson and Rundell were painfully aware that the

decade-long efforts to reintroduce snails to Chittenango Falls have not offset

the wild population’s decline. “Even captive breeding is unlikely to save the

day for these snails,” Rundell said.

On that sunny

Thursday, the surveyors tried to find as many wild snails as possible in 15

minutes, placing them in Tupperware containers and, later, under a park

pavilion, sorting through the animals and inspecting them closely. The snails

would be released back into the environment once tiny numbered tags had been

super glued to their shells.

A dark spot on

the foot of a Chit distinguishes it from what the researchers refer to as

Species B — Succinea putris, an invasive land snail that is native to

Appalachia and now also lives in the Chits’ habitat and may compete for

resources. Little is known about Species B’s interactions.

“I get emails

all the time, like, ‘I found a Chit; it’s in my backyard,’ ” Gilbertson said.

“And I look, and it’s Species B.”

After an hour of

sorting, the team collected five Chits. Two had been caught earlier in the

summer; one had been released from the captive population a year ago and had a

white tag on its shell; two were new finds. “I’m really happy to see some fresh

snails,” Gilbertson said. “It gives me hope.”

She added: “By

going into this tiny world, we’re able to see something that we don’t normally

see. And I think that in general, people don’t realize that the little guys are

just as important for conserving.”

Before departing, a few of the researchers walked

back down to the falls to release the snails that had been collected as well as

the five snails that Gilbertson had picked out of the captive population for

reintroduction. The sun shone directly overhead, and water spilled down the

falls like white paint. Every bit of ground was drenched in sunlight and

steaming in the heat, except for the living room that harbored the only wild

population of Chittenango ovate amber snails in the world. This corner of the

Earth was cool, shady and damp — just right.

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News