LONDON — In a love letter from 1745 decorated with a

doodle of a heart shot through with arrows, María Clara de Aialde wrote to her

husband, Sebastian, a Spanish sailor working in the colonial trade with

Venezuela, that she could “no longer wait” to be with him.

اضافة اعلان

Later that same year, an amorous French seaman who signed

his name M. Lefevre scrawled romantic lines from a French warship to a certain

Marie-Anne Hoteé back in Brest.

Fifty years later, a missionary in Suriname named Lene Wied,

in a lonely letter back to Germany, complained that war on the high seas had

choked off any news from home: “Two ships which have been taken by the French

probably carried letters addressed to me.”

None of those lines ever reached their intended recipients.

British warships instead snatched those letters, and scores more, from aboard

merchant ships during wars from the 1650s to the early 19th century.

While the ships’ cargoes — sugar from the Caribbean, tobacco

from Virginia, ivory from Guinea, enslaved people bound for the Americas —

became war plunder, the papers were bundled off to so-called “prize courts” in

London as potential legal proof that the seizures were legitimate spoils of

war.

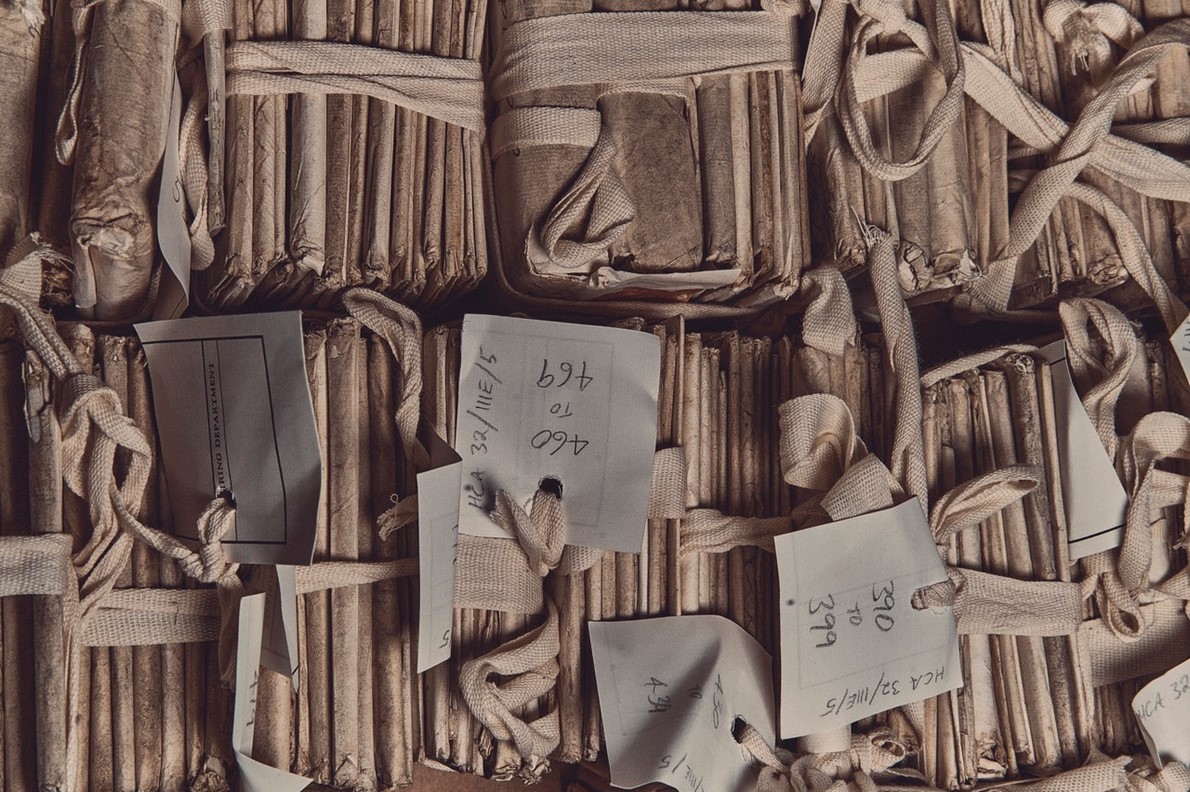

For centuries since, the bulging boxes of those undelivered

letters, seized from around 35,000 ships, sat neglected in British government

storage, a kind of half-forgotten dead letter office for intercepted mail.

Photo equipment for

visual documentation of a cache of undelivered mail, at the British National

Archives in London.

Photo equipment for

visual documentation of a cache of undelivered mail, at the British National

Archives in London.

Poorly sorted and only vaguely cataloged, the Prize Papers,

as they became known, have now begun revealing lost treasures. Archivists at

Britain’s National Archives and a research team at the Carl von Ossietzky

University of Oldenburg in Germany are working on a joint project to sort,

catalog, and digitize the collection, which gives a nuanced portrait of private

lives, international commerce, and state power in an age of rising empires.

From business dealings to original poemsThe project, expected to last two decades, aims to make the

collection of more than 160,000 letters and hundreds of thousands of other

documents, written in at least 19 languages, freely available and easily

searchable online.

Many of the papers have not been read in centuries, and many

letters remain sealed and unopened.

For centuries since, the bulging boxes of those undelivered letters, seized from around 35,000 ships, sat neglected in British government storage

“You find so many individual voices by men, women —

children, even — who speak, not as a colonial administrator, but as a person

abroad,” said Dagmar Freist, a historian at the Carl von Ossietzky University of

Oldenburg who directs the Prize Papers Project. “They would describe their

social interactions with other religious groups, with enslaved people, with

rituals and traditions,” she added. “It allows you insights into everyday

life.”

The paperwork of colonial commerce makes up much of

collection: invoices for goods, contracts, bills of lading. Reports from the

managers of colonial slave plantations, dispatched to owners and investors in

Europe, also turn up frequently.

But some are poignant and personal. A German sailor on a

merchant ship captured in the 18th century copied out a poem for his daughter’s

baptism. One letter mailed back to Europe requesting a new pair of shoes

includes the traced outline of the writer’s foot to match the size.

An intercepted cache of letters to Spanish prisoners of war

from their wives and children on Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands, includes

complaints about the hardship of scratching out a living alone during wartime,

and details the outbreak of an epidemic on the island: “Distemper begun with

Pains in the head, Stitches, lowness of Spirits & a loathing of the

Stomach.”

‘A wild archive’Archivists and a team of volunteers have begun sorting the

documents — some still coated in soot and grease, and smelling of the filthy

1800s London air — in some cases, matching paper creases or other marks to

bring together scattered pages.

Conservators at the National Archives clean and preserve the

collection, while two photographers, hired by the project through the German

Historical Institute London, meticulously document the intricate work.

“This is like a wild archive,” said Amanda Bevan, who leads

the National Archives team. “All the work I’ve done the rest of my career has

been on documents which were already in good order, identified, numbered.”

“What amazed me was how much the letters — even the ones which have been opened at some point, but they’re still folded up — retain a ‘paper memory. They’re folded in quite intricate patterns.”

Prying the lid off an archival box recently, Bevan pulled

out a mailbag from the Zenobia, a merchant ship captured while sailing from

France to New York during the War of 1812. Inside were dozens of letters —

still sealed with wax — bearing addresses all across the East Coast: Baltimore,

Boston, Charleston, New York, Philadelphia.

‘Electrifying’ discoveriesFreist, the project director, first heard about the

collection from historians in the Netherlands who digitized a selection of the

Dutch-language documents. A Dutch television program called “Letters Over

Water” that aired from 2011 to 2013 tracked down some letter writers’

descendants to deliver the centuries-old intercepted mail.

On early visits to the National Archives, in Kew, South

London, Freist and her team selected archival boxes at random and marveled over

the contents. Freist said she was “electrified” when archivists opened several

letters and found jottings on chalkboard tablets that had only survived

unerased because of their sudden seizure.

“What amazed me was how much the letters — even the ones

which have been opened at some point, but they’re still folded up — retain a

‘paper memory,’” Bevan said. “They’re folded in quite intricate patterns.”

A cache of letters taken from a ship bound from Cádiz,

Spain for Veracruz, Mexico.

A cache of letters taken from a ship bound from Cádiz,

Spain for Veracruz, Mexico.

Sometimes, cascading inserts and enclosures fold out from

inside a single stuffed envelope, with additional letters meant to be passed on

to other relatives or friends. Those packages unfold like matryoshka dolls,

with letters for elderly parents wrapped around letters for siblings and

spouses, enclosing short notes for children, or hiding small gifts like rings,

or, in one instance, a single coffee bean.

So far, the team has gone through documents seized during

the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) in close detail but have taken

only cursory looks at files from other wars.

“We haven’t looked at everything yet, so we’re bound to find

more stuff,” Bevan said. “We open each box and we’re not quite sure what we’re

going to find.”

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News