“I never trust the mind of an iceberg,” Cecil Stockley said.

He estimates its length, multiplies by five and keeps his boat at least that

distance away.

اضافة اعلان

Dave Boyd said his safety rules depend on which type of

iceberg he is dealing with. “A tabular is generally pretty mellow,” Boyd

explained as we floated off the coast of Newfoundland, referring to icebergs

with steep sides and large, flat tops. “But a pinnacle” — a tall iceberg with

one or more spires — “can be a real beast.”

Barry Rogers does not just look at an iceberg; he listens to

it, as well. When the normal Rice Krispies-like pop of escaping air bubbles

gives way to a much louder frying-pan sizzle, the iceberg may be about to roll

over or even split apart, he explained. Another clue, he said, is when a flock

of seabirds perched atop the ice abruptly peels away en masse. They can feel

the tremors that Rogers is straining to hear.

An iceberg glides past Change Islands, about an hour and a

half from Twillingate by car and ferry, in Newfoundland, Canada, May 22, 2023.

An iceberg glides past Change Islands, about an hour and a

half from Twillingate by car and ferry, in Newfoundland, Canada, May 22, 2023.

“Either way, if that’s happening — it’s time to get the hell

out of Dodge,” he said.

Stockley, Boyd and Rogers are all skippers — with more than

100 years of combined experience among them — for tour boat companies who hunt

for giant blocks of ice and snow in Iceberg Alley, the nickname for a stretch

of water curving along the eastern coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, the

easternmost province of Canada. Icebergs that have calved off the giant

Greenland ice sheet pass by here each spring on a slow-motion journey southward

to the open waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

An iceberg near the town of Twillingate,

Newfoundland, Canada, May 22, 2023

An iceberg near the town of Twillingate,

Newfoundland, Canada, May 22, 2023.

In 1912, one such iceberg struck the starboard side of the

Titanic on its maiden voyage across the Atlantic. Over the years, plenty of

others have done lesser damage to ships, oil rigs and even the occasional

unlucky — or foolhardy — kayaker.

But the vast majority of these icebergs, melting as they

move south into warmer water, don’t hit anything at all before they disappear

into the sea.

Prime Berth, a museum and

heritage center in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May 21, 2023.

Prime Berth, a museum and

heritage center in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May 21, 2023.

As they do, it makes for a truly spectacular show: an eerily

opalescent display of colossal icebergs — some looming like high mesas, others

spindly and rising like the Matterhorn — destined for decay.

I saw dozens of these mesmerizing icebergs while riding on

boats, standing on shore and staring out the window of a descending airplane

during a meandering trip in May that took me from St. John’s, the provincial

capital, to the Avalon Peninsula (the southeast section of the island of

Newfoundland) and up to Twillingate, a charming coastal island in north central

Newfoundland that proclaims itself the “Iceberg Capital of the World”.

Stuffed puffins are seen on a tour with Iceberg Quest in

Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May 21, 2023.

Stuffed puffins are seen on a tour with Iceberg Quest in

Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May 21, 2023.

Twillingate has competitors for that mantle, but I can’t

imagine there’s a better place on the planet to learn about icebergs — what

causes them to form, why their colors vary, and how they travel and die. It is

fascinating, for example, to contemplate that the berg before you today began

as snowfall thousands of years ago. There is also the seemingly endless number

of ways to classify an iceberg, depending on its type, composition, color, size

and the various effects of the wind, waves, and sun that sculpt its shape.

Or, as an educational display on icebergs at the local

lighthouse puts it: “Each one is a unique individual.”

In Twillingate, this connoisseur’s appreciation for an

iceberg’s precise characteristics coexists with a certain nonchalance that

comes from seeing the annual offshore parade of moving blocks of snow and ice

that can reach the size of lower Manhattan in New York City.

Items displayed at Prime

Berth, a museum and heritage center in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May

21, 2023.

Items displayed at Prime

Berth, a museum and heritage center in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May

21, 2023.

I had a hankering to visit Iceberg Alley ever since 2017,

when I came across a remarkable photograph depicting an iceberg as tall as a

15-story building that had managed to beach itself alongside the tiny fishing

village of Ferryland, an hour or so south of St. John’s.

The brightly painted houses on shore seemed like dollhouses

compared with the colossal wall of snow hulking over the place. I found it

fascinating that people who lived there could watch the show while sipping

morning coffee on their decks.

In a sense, my trip began well before I arrived in the

province. A sucker for autumn foliage maps that show where the peak colors are

in my native New England, I had become obsessed with a springtime counterpart:

icebergfinder.com. The website does exactly what its name suggests, and it is

where Iceberg Alley fans post excited comments and dramatic photographs the way

others do with sunsets or birds.

Speaking of birds, there are mind-boggling numbers of them

in Newfoundland this time of year — about half a million Atlantic puffins, to

name just one species — joined by one of the greatest concentrations of

migrating humpback whales found anywhere. Along with the icebergs, the birds

and whales make for the province’s camera-ready trifecta, usually on display

from about mid-May through the end of June.

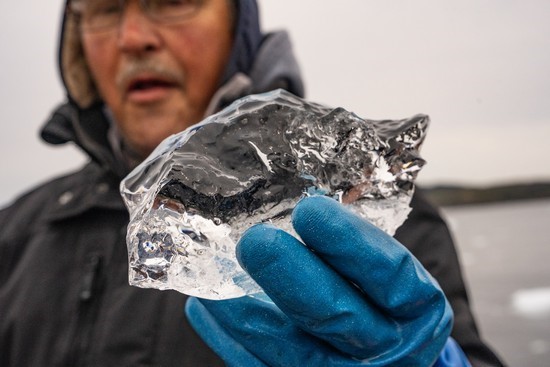

Dave Boyd discusses the

composition of a small chunk of ice in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May

22, 2023.

Dave Boyd discusses the

composition of a small chunk of ice in Twillingate, Newfoundland, Canada, May

22, 2023.

Actually, one could make it a quadfecta and throw in a look

at the Titanic, history’s most famous iceberg casualty, which now rests some

3,810m underwater and a few hundred miles southeast of Newfoundland. For that,

though, you do need to pony up $250,000, the cost of a nine-day passage aboard

a research ship with OceanGate Expeditions.

In St. John’s I ran into OceanGate’s founder, a fellow

Seattleite named Stockton Rush who proudly showed me the ship and his 7m Titan,

the carbon fiber and titanium submarine he uses to take his mission specialists

(i.e., customers) down to the ocean floor for a five-hour look around the

stricken liner and its huge debris field.

I admire Stockton’s passion but lacked the money needed to

become a mission specialist. For a considerably lesser fare of about $75, I

instead stayed above the waterline and went seeking icebergs aboard a 63-foot

ship owned by a company named Iceberg Quest. Barry Rogers, the skipper who uses

his multiply-by-five formula for keeping away from icebergs, kept up a steady

stream of narration during the two-hour out-and-back tour to Cape Spear, a jut

of land that happens to be the easternmost point in North America.

I found the people in Newfoundland to be friendly, funny,

and frank, if a bit stubborn in their ways. They even insist on their own time

zone, a half-hour ahead of provincial mate Labrador and the rest of Atlantic

Canada. Being closer to Galway on Ireland’s West Coast than they are to

Winnipeg, many Newfoundlanders still have accents traceable to their Irish and

English ancestors who settled the land.

An iceberg in Newfoundland, Canada, May 20, 2023.

An iceberg in Newfoundland, Canada, May 20, 2023.

In Twillingate, I signed on with Boyd, who runs a 8.5m,

12-passenger aluminum boat named the Silver Bullet, which he deftly maneuvered

into close enough range that we could see the turquoise underbelly of a tabular

iceberg. The white above-water mass was laced with lines of a rich royal-blue

color, which were essentially narrow channels cut by melting water. (Similar

channels in some algae-heavy icebergs make them look for all the world like

giant green-striped peppermints, but most have hues of blue.)

Here, by the way, is as good a place as any to include the

caveat that what I saw was only — and I’m sorry I have no more creative way to

say it, which is why I waited — the tip of the icebergs.

Normally, what you and I see of any given iceberg above the

surface of the water is only 10 percent to 12 percent of its total mass,

explained Stephen E. Bruneau, an ice expert at Newfoundland’s Memorial

University and author of the super-definitive book, “A Field Guide to Icebergs

of Newfoundland and Labrador.”

I did come across an iceberg melting in real time, late one

afternoon while I was poking around the back roads of New World Island, a few

miles south of Twillingate. The scene was hypnotic: The berg had managed to

beach itself in a secluded cove up against a larger tabular iceberg, and it was

taking a pounding from the incoming surf. I watched it diminish over the course

of an hour from twin-spired grandeur to a double humpback to a bereft-looking

bulbous mound.

But then I noticed that, in its dying hours, it was actually

protecting the larger iceberg behind it, enabling its cousin to live to fight

another day, or at least another tidal cycle. The iceberg had performed a noble

sacrifice. A unique individual, indeed.

Read more Odd and Bizarre

Jordan News