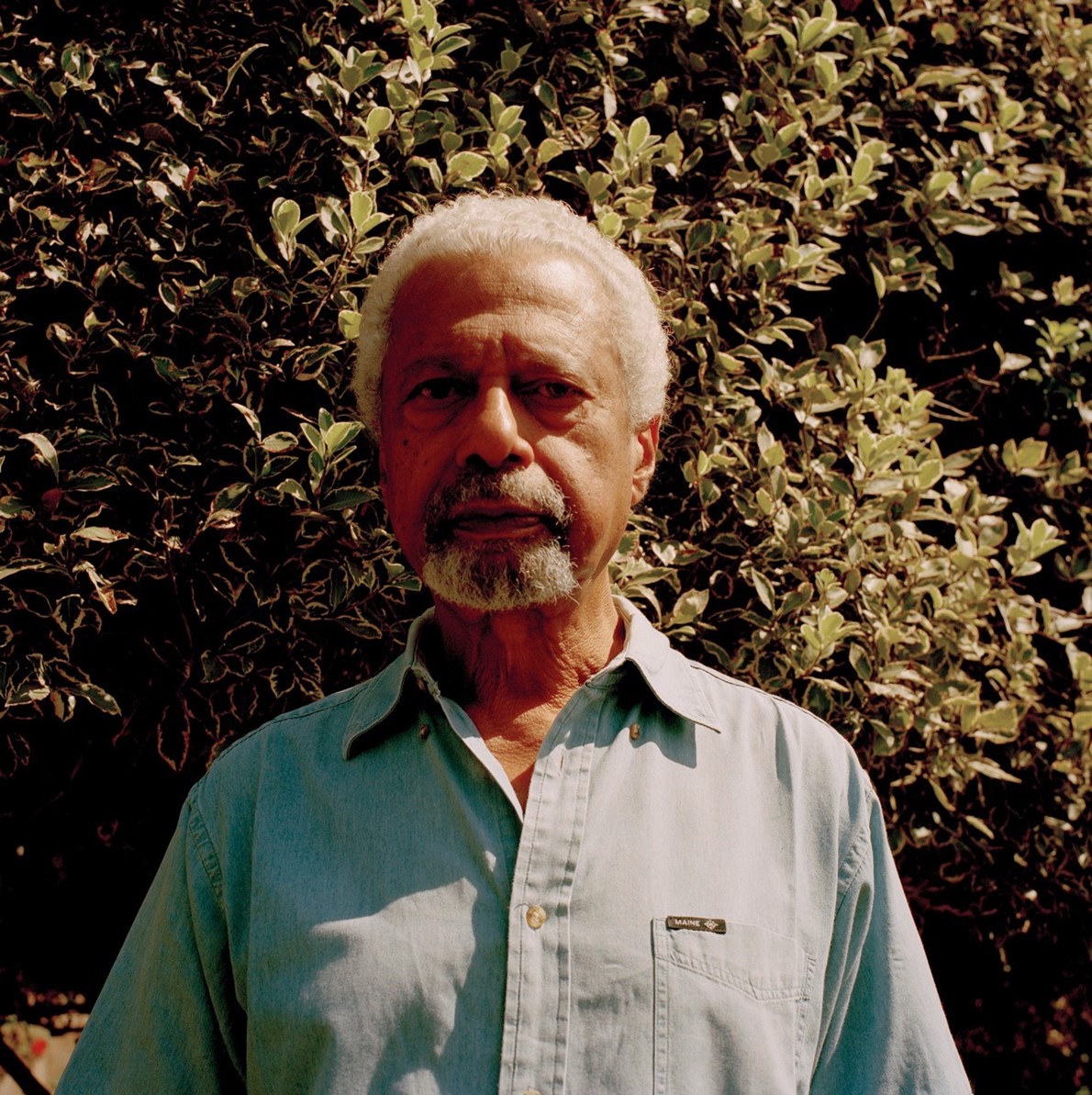

STURRY, England — From the first time he was ever interviewed,

around the publication of his debut novel in 1988, author Abdulrazak Gurnah has

been facing attempts to categorize him and his work: Does he think of himself

as an African writer? Or a British one? Who does he speak for: this group or

that one?

اضافة اعلان

Even after

winning the Nobel Prize in literature last year — an award given to only four

other African-born writers before him, including Wole Soyinka and Naguib

Mahfouz — he was asked at a news conference about “the controversy over your

identity.” People were apparently confused about how to define him.

“What

controversy?” he recalled replying. “I know who I am!”

Gurnah, 73,

moved to Britain from Zanzibar, where he was born, in 1968. During the decades

that followed, he honed his craft and eventually found quiet recognition as a

novelist. His books often featured East Africa’s colonial era and its

aftermath, the immigrant experience in Britain, or both — and as a result he

has sometimes had to push back against the idea that he speaks for anyone other

than himself.

“The idea that a

writer represents, I resist,” he said. “I represent me. I represent me in terms

of what I think and what I am, what concerns me, what I want to write about.”

He added: “When

I speak, I’m speaking as a voice among many, and if you hear an echo in your own

experience, that’s great.”

Even

postcolonial writing, like his, which deals with the process of colonization

and its aftermath, he said, is about “experience, not about where.”

Readers the

world over have indeed found a profound connection to his writing regardless of

their background. Gurnah was awarded the Nobel for his life’s work: His 10

novels include “By the Sea,” about an aging asylum-seeker trying to build a

life on Britain’s south coast, and “Paradise,” which was shortlisted for the

Booker Prize in 1994.

Since the Nobel

was announced last October, his books, many of which were out of print in the

US at the time, have been reissued. They have been translated into 38

languages, including the first translation of his work into Swahili, the main

language of his birthplace.

Sitting one

recent morning in the living room of his home in the sleepy town of Sturry,

southeast England, its walls decorated with palm-frond patterned wallpaper and

friends’ paintings, he said he was anticipating the release this month of

novels in Estonian, Polish, and Czech.

He was also

expecting more attention in the United States, where “Afterlives,” about three

people struggling as Germany and Britain fight over East Africa, will be

released Tuesday by Riverhead Books. (It came out in Britain, by Bloomsbury, in

2020.)

Alexandra

Pringle, Gurnah’s longtime British editor, said the book showed his ability to

tell stories “of large historical events through small lives” with subtle

prose, which is “the hardest to achieve.” Many readers stereotype African

authors, expecting them to be showy in their writing, Pringle added. “That is

not Abdulrazak,” she said.

Friends and

admirers agreed with that assessment. Author Maaza Mengiste met him for lunch

after his Nobel win and said he was “gracious and kind as you would imagine

from his books,” but also very funny, telling her about breaking the news to

his grandchildren, only to have them greet it with an “OK, Grandpa,” unaware of

its significance.

Gurnah grew up

in Zanzibar when it was both a British protectorate and a sultanate. His father

traded dried and preserved fish caught in the Indian Ocean, and much of his

early life was focused on the shoreline near his doorstep. In “Map Reading,” a

short collection of Gurnah’s essays that is coming Nov. 24 from Bloomsbury, he

describes how almost every November so many dhows packed into the harbor that

he would watch the sailors walk from one to another, heaving with goods, as if

it were land.

His childhood

was first disrupted in 1964, when rebels overthrew Zanzibar’s largely Arab

government. Gurnah was on a family holiday in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest

city, on the day of the revolution, but watched the “pitiful sight” of

Zanzibar’s fleeing sultan and former British officials arriving at its port.

When he returned to Zanzibar, the family drove past “burned out houses, bullet

holes in the walls,” and realized that something terrible had happened. Gurnah

didn’t see any violence himself, he said, “but you didn’t have to witness it;

you constantly heard about it.”

The new

government shut the schools, then reopened them, only to require graduates to

become teachers, largely in rural areas, Gurnah said. Sensing they had little

future, Gurnah and his brother left for England, where a cousin was studying.

They carried just 400 British pounds, about $480, to survive.

After finishing

the equivalent of high school in England, Gurnah worked as a hospital orderly

for three years to survive before he attended university. And eventually he

began to write — first sketches about home, much later full novels.

In his Nobel

lecture, he said the impulse came “in my homesickness and amidst the anguish of

a stranger’s life.” He realized, he said, “there was something I needed to

say.”

The writing

first reflected what had happened in Zanzibar, he added, but quickly swelled to

include issues of colonialism and its legacy, as well as his treatment in

England.

“A desire grew

to write in refusal of the self-assured summaries of people who despised and

belittled us,” Gurnah said in his Nobel lecture, although he added he never

wanted to write polemics, only books filled with humankind’s capacity for

tenderness amid cruelty, and for kindness, even from unexpected sources.

Gurnah’s fans

say the humanity in his work is one of its strongest points. Mengiste said his

novels show that “it’s possible for people to exist within catastrophes or

political systems that are devastating and still maintain their humanity, still

fall in love, still create families.” That was “a subtly political statement,”

she said.

His most

acclaimed work reflects that approach. “Paradise” was conceived after Gurnah

was allowed to return to Zanzibar for the first time, in 1984. One day he stood

at a window watching his father walk to a mosque and realized that the elder

Gurnah would have been just a child when Britain was establishing a

protectorate in Zanzibar. Gurnah said he “wondered how that would have seemed

to a child, the beginning of recognition that strangers have taken over your

lives.” The novel he wrote is as much a boy’s coming-of-age story, and about

children being used as collateral for debts, as it is about colonialism.

“Afterlives,” a

similarly historical novel, had its origins in wanting to write about the war

between Britain and Germany in East Africa, which had previously been portrayed

in novels, Gurnah said, “as a bit of a picnic,” even though hundreds of

thousands of civilians died from war-related famines and disease. One of its

central characters, Hamza, signs up to join the German army and is trapped in

service despite quickly realizing his mistake. When he eventually leaves, he’s

an injured stranger to his hometown, yet rebuilds his life, caught up in

romance.

Winning the

Nobel, and the new fame that came with it, required some adjustments: He has

had no time to write, Gurnah said. His schedule has been packed with interviews

and with occasional trips abroad, including a return to Zanzibar, where he was

treated as a hero for the first time, despite few of his books being available

there.