I have many fears as a mother. My kindergarten-age

daughter recently learned a game on the school bus called “Truth or Force”. My

youngest refuses to eat almost anything but Kraft Mac & Cheese. Added to

the list this year, alongside outside influences and health concerns, is the

possibility that my daughters could inadvertently lock me out of my digital

life.

اضافة اعلان

That is what happened to a mother in Colorado whose

nine-year-old son used her old smartphone to stream himself naked on YouTube,

and a father in San Francisco whose Google account was disabled and deleted because

he took naked photos of his toddler for the doctor.

I reported on their experiences for The New York Times, and as I

talked to these parents, who were stunned and bereft at the loss of their

emails, photos, videos, contacts, and important documents spanning decades, I

realized I was similarly at risk.

I am “cloud-complacent,” keeping my most important digital

information not on a hard drive at home but in the huge digital basement

provided via technology companies’ servers. Google gives all users 15 gigabytes

free, one-quarter of what comes standard on an Android phone, and I have not

managed to max it out in 18 years of using the company’s many services.

I did fill up Apple’s free 5GB, so I now pay $9.99 a month for

additional iCloud storage space. Meta has no max; like scrolling on Instagram,

the allowed space is infinite.

If I were suddenly cut off from any of these services, the data

loss would be professionally and personally devastating.

As a child of the 1980s, I used to have physical constraints on

how many photos, journals, VHS tapes, and notes passed in seventh grade that I

could reasonably keep. But the immense expanse and relatively cheap rent of the

so-called cloud has made me a data hoarder. Heading into 2023, I set out to

excavate everything I was storing on every service, and find somewhere to save

it that I had control over. As I grappled with all the gigabytes, my concern

morphed from losing it all to figuring out what was actually worth saving.

Data harvestingI find nearly 100 photos from one November night 15 years ago,

out with my family at a Tampa Bay Lightning game when my sisters and I were

home for the holidays. We were tailgating with a mini-keg of Heineken. My dad

is posing by the car, making a funny face at the ridiculousness of a parking

garage party. Then, we were posing in the stadium with the hockey rink in the

background, toasting with a stranger we sat next to. Had we bonded with him

during an especially close third period? The metadata in the Google Photos JPG

file did not say.

The photos transported me back to a tremendously fun evening

that I had all but forgotten. Yet I wondered how there could be so many photos

from just one night. How do I decide which to keep and which to get rid of?

This kind of data explosion is a result of economics, said

Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive, a nonprofit group based in San

Francisco that saves copies of websites and digitizes books and television

shows. Taking a photo used to be expensive because it involved film that needed

to be developed.

“It cost a dollar every time you hit a shutter,” Kahle said.

“That’s no longer the case so we hit the shutter all the time and keep way, way

too much.”

I had captured the 2007 evening in Tampa, Florida,

pre-smartphone on a digital Canon camera that had a relatively small memory

card that I regularly emptied into Google Photos. I found more than 4,000 other

photos there, along with 10 gigabytes of data from Blogger, Gmail, Google Chat,

and Google Search, when I requested a copy of the data in my account using a

Google tool called Takeout.

I just pressed a button and a couple of days later got my data

in a three-file chunk, which was great, although some of it, including all my

emails, was not human-readable. Instead, it came in a form that needed to be

uploaded to another service or Google account.

According to a company spokesperson, 50 million people a year

use Takeout to download their data from 80 Google products, with 400 billion

files exported in 2021. These people may have had plans to move to a different

service, simply wanted their own copy or were preserving what they had on

Google before deleting it from the company’s servers.

Takeout was created in 2011 by a group of Google engineers who

called themselves the Data Liberation Front. Brian Fitzpatrick, a former Google

employee in Chicago who led the team, said he thought it was important that the

company’s users had an easy “off ramp” to leave Google and take their data

elsewhere. But Fitzpatrick said he worried that when people stored their

digital belongings on a company’s server, they “don’t think about it or care

about it”.

Some of my data landlords were more accommodating than others.

Twitter,

Facebook, and Instagram offered Takeout-like tools, while Apple had a

more complicated data transfer process that involved voluminous instructions

and a USB cable.

The amount of data I eventually pulled down was staggering,

including more than 30,000 photos, 2,000 videos, 22,000 Twitter posts, 57,000

emails, 15,000 pages of old Google chats and 16,000 pages of Google searches

going back to 2011.

The missingThe trove of data brought forgotten episodes of my life back in

vivid color. A blurry photo of my best friend’s husband with a tiny baby

strapped to his chest, standing in front of a wall-size Beetle juice an face,

made me recall a long-ago outing to a Tim Burton exhibit at a museum in Los

Angeles.

I do not remember what I learned about the gothic filmmaker, but

I do remember my friends’ horror when their weeks-old son, now 11, had a

blowout and they had to beg a comically oversize diaper from a stranger.

The granularity of what was in my digital archive accentuated

the parts of my life that were missing entirely: emails from college in a

university-provided account that I hadn’t thought to migrate; photos and videos

I took on an Android phone that I backed up to an external hard drive that has

since disappeared; and stories I had written in journalism school for publications

that no longer exist. They were as lost to me as the confessional journal I

once left in the seatback of a plane. The idea that information, once

digitized, will stick around forever is flawed.

Margot Note, an archivist, said members of her profession

thought a lot about the accessibility of the medium on which data was stored,

given the challenge of recovering videos from older formats such as DVDs, VHS

tapes, and reel film. Note asks the kinds of questions most of us do not: Will

there be the right software or hardware to open all our digital files many

years from now? With something called “bit rot” — the degradation of a digital

file overtime — the files may not be in good shape.

Individuals and institutions think that when they digitize material

it will be safe, she said. “But digital files can be more fragile than physical

ones.”

Where to put itOnce I assembled my data Frankenstein, I had to decide where to

put it. More than a decade ago, pre-cloud complacency, I would regularly back

my stuff up to a hard drive that I probably bought at Best Buy. Digital

self-storage has gotten more complex as I discovered when I visited the

Data Hoarder subreddit. Posts there with technical advice for the best home setup

were jargon-filled to the point of incomprehension for a newbie. A sample post:

“Started with single bay Synology Nas and recently built a 16TB unRAID server on

a xeon 1230. Very happy with result.”

I felt as if I had landed on an alien planet, so I turned

instead to professional archivists and tech-savvy friends. They recommended two

$299 12-terabyte hard drives, one of which should have ample room for what I

have now and what I will create in the future, and another to mirror the first,

as well as a $249 NAS, or network-attached storage system, to connect to my

home router, so I could access the files remotely and monitor the health of the

drives.

Getting all your data and figuring out how to securely store it

is cumbersome, complicated and costly. There is a reason most people ignore all

their stuff in the cloud.

What to keepI noticed a philosophical divide among the archivists I spoke

with. Digital archivists were committed to keeping everything with

the mentality that you never know what you might want one day, while

professional archivists who worked with family and institutional collections

said it was important to pare down to make an archive manageable for people who

look at it in the future.

Bob Clark, the director of archives at the Rockefeller Archive

Center, said that the general rule of thumb in his profession was that less

than 5 percent of the material in a collection was worth saving. He faulted the

technology companies for offering too much storage space, eliminating the need

for deliberating over what we keep.

“They’ve made it so easy that they have turned us into

unintentional data hoarders,” he said.

The companies try, occasionally, to play the role of memory

miner, surfacing moments that they think should be meaningful, probably aiming

to increase my engagement with their platform or inspire brand loyalty. But

their algorithmic archivists inadvertently highlight the value of human

curation.

“I don’t think we can simply rely on the algorithms to help you

decide what’s important or not,” Clark said. “There need to be points of human

intervention and judgment involved.”

Paring it downRather than just keeping a full digital copy of everything, I

decided to take the archivists’ advice and pare it down somewhat, a process the

professionals call appraisal. An easy place to start was the screenshots: the

QR codes for flights long ago boarded, privacy agreements I had to click to use

an app, emails that were best forwarded to my husband via text and a message

from Words With Friends that “nutjob” was not an acceptable word.

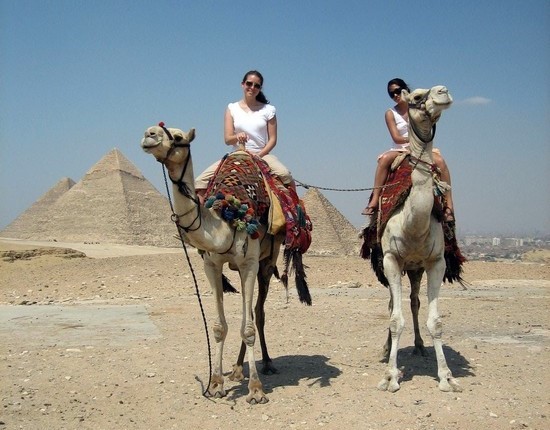

There were some clear keepers: a selfie I took in Beijing with

artist Ai Weiwei in April 2015; a video of my eldest daughter’s first steps in

December 2017; and a shot of me on a camel in front of the Giza Pyramids in

2007, a photo I had purposely staged to recreate one we had on my childhood

refrigerator of my great-grandmother in the same place doing the same thing,

but with a disgruntled expression on her face.

Then there is the stuff I’m ambivalent about, like the many

photos with long-ago exes, which for now I’ll continue to hoard given that I’m

still on good terms with them and I’m not going to fill up 12 terabytes any

time soon.

There was also a lot of “data exhaust,” as security technologist

Matt Mitchell calls it, a polite term for the record of my life rendered in

Google searches, from a 2011 query for karaoke bars in Washington to a more

recent search for the closest Chuck E. Cheese. I will not keep those on my

personal hard drive, and I may take the step of deleting them from Google’s

servers, which the company makes possible, because their embarrassment

potential is higher than their archival value.

Mitchell said super hoarders should pare down, not to make

memories easier to find, but to eliminate data that could come back to bite

them.

“You need to let go because you can’t get hacked if there’s

nothing to hack,” said Mitchell, the founder of Crypto Harlem, a cybersecurity

education nonprofit. “It’s only when you’re storing too much that you run into

the worst of these problems.”

Inactive accountsRight now, it is cheap to hoard all this data in the cloud.

“The cost of storage long term continues to fall,” said George

Blood, who runs a business outside Philadelphia digitizing information from

obsolete media, creating 10 terabytes of data per day, on average. “They may

charge you more for the cost of the electricity — spinning the disk your data

is on — than the storage itself.”

Big technology companies do not often prompt people to minimize

their data footprints, until, that is, they near the end of their free storage

space. That is when companies force them to decide whether to move to the paid

plans. There are signs, though, that the companies do not want to hold on to

our data forever: Most have policies allowing them to delete accounts that are

inactive for a year or more.

Aware of the potential value of data left behind by those who

euphemistically go “inactive,” Apple recently introduced a legacy contact

feature, to designate a person who can access an Apple account after the

owner’s death. Google has long had a similar tool, prosaically called inactive

account manager. Facebook created legacy contacts in 2015 to look after

accounts that have been

memorialized.

And that really is the ultimate question around personal

archives: What becomes of them after we die? By keeping so much, more than we

want to sort through, which is almost certainly more than anyone else wants to

sort through on our behalf, we may leave behind less than previous generations

because our accounts will go inactive and be deleted. Our personal clouds may

grow so vast that no one will ever go through them, and all the bits and bytes

could end up just blowing away.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News