The ocean’s biggest garbage pile is full of floating life

New York Times

last updated: May 08,2022

In 2019, French swimmer Benoit Lecomte swam more than 300

nautical miles through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch to raise awareness about

marine plastic pollution.

As he swam, he

was often surprised to find that he was not alone.

“Every time I

saw plastic debris floating, there was life all around it,” Lecomte said.

The patch was

less a garbage island than a garbage soup of plastic bottles, fishing nets,

tires and toothbrushes. And floating at its surface were blue dragon

nudibranchs, Portuguese man-o-wars and other small surface-dwelling animals,

which are collectively known as neuston.

Scientists

aboard the ship supporting Lecomte’s swim systematically sampled the patch’s

surface waters. The team found that there were much higher concentrations of

neuston within the patch than outside it. In some parts of the patch, there

were nearly as many neuston as pieces of plastic.

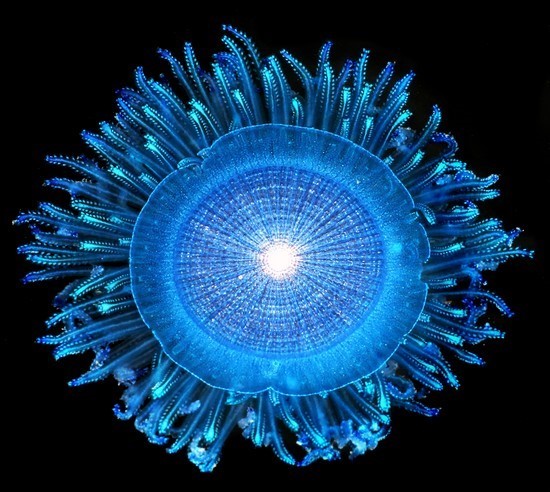

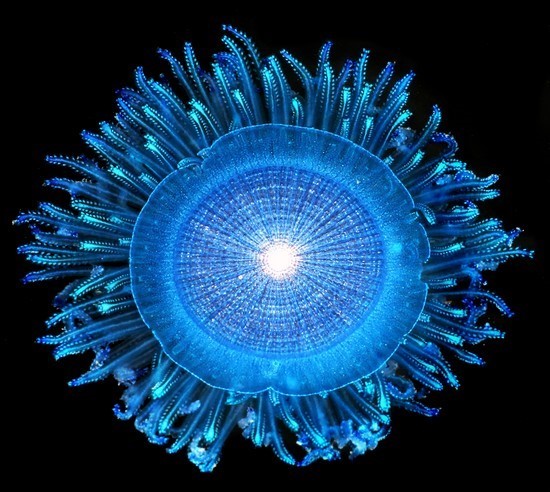

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the blue button Porpita species, viewed from above.

“I had this

hypothesis that gyres concentrate life and plastic in similar ways, but it was

still really surprising to see just how much we found out there,” said Rebecca

Helm, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina and co-author

of the study. “The density was really staggering. To see them in that

concentration was like, wow.”

The findings

were posted last month on bioRxiv and have not yet been subjected to peer

review. But if they hold up, Helm and other scientists say, it may complicate

efforts by conservationists to remove the immense and ever-growing amount of

plastic in the patch.

The world’s

oceans contain five gyres, large systems of circular currents powered by global

wind patterns and forces created by Earth’s rotation. They act like enormous

whirlpools, so anything floating within one will eventually be pulled into its

center. For nearly a century, floating plastic waste has been pouring into the

gyres, creating an assortment of garbage patches. The largest, the Great

Pacific Patch, is halfway between Hawaii and California and contains at least

79,000 tons of plastic, according to the Ocean Cleanup Foundation. All that

trash turns out to be a great foothold for living things.

Helm and her

colleagues pulled many individual creatures out of the sea with their nets:

by-the-wind sailors, free-floating hydrozoans that travel on ocean breezes;

blue buttons, quarter-sized cousins of the jellyfish; and violet sea-snails,

which build “rafts” to stay afloat by trapping air bubbles in a soaplike mucus

they secrete from a gland in their foot. They also found potential evidence

that these creatures may be reproducing within the patch.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the snail Recluzia species, viewed from the side oral end.

“I wasn’t surprised,”

said Andre Boustany, a researcher with the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California.

“We know this place is an aggregation area for drifting plastics, so why would

it not be an aggregation area for these drifting animals as well?”

Little is known

about neuston, especially those found far from land in the heart of ocean

gyres.

“They are very

difficult to study because they occur in the open ocean and you cannot collect

them unless you go on marine expeditions, which cost a lot of money,” said

Lanna Cheng, a research scientist at the University of California, San Diego.

Because so

little is known about the life history and ecology of these creatures, this

study, though severely limited in size and scope, offers valuable insights to

scientists.

But Helm said

there is another implication of the study: Organizations working to remove

plastic waste from the patch may also need to consider what the study means for

their efforts.

There are

several nonprofit organizations working to remove floating plastic from the

Great Pacific Patch. The largest, the Ocean Cleanup Foundation in the

Netherlands, developed a net specifically to collect and concentrate marine

debris as it is pulled across the sea’s surface by winds and currents. Once the

net is full, a ship takes its contents to land for proper disposal.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows a buoy barnacle, Dosima fascicularis, viewed from the side, with aboral white float at the water’s surface.

Helm and other

scientists warn that such nets threaten sea life, including neuston. Although

adjustments to the net’s design have been made to reduce bycatch, Helm believes

any large-scale removal of plastic from the patch could pose a threat to its

neuston inhabitants.

“When it comes

to figuring out what to do about the plastic that’s already in the ocean, I

think we need to be really careful,” she said. The results of her study “really

emphasize the need to study the open ocean before we try to manipulate it,

modify it, clean it up or extract minerals from it.”

Laurent

Lebreton, an oceanographer with the Ocean Cleanup Foundation, disagreed with

Helm.

“It’s too early

to reach any conclusions on how we should react to that study,” he said. “You

have to take into account the effects of plastic pollution on other species. We

are collecting several tons of plastic every week with our system — plastic

that is affecting the environment.”

Plastic in the

ocean poses a threat to marine life, killing more than 1 million seabirds every

year, as well as more than 100,000 marine mammals, according to UNESCO.

Everything from fish to whales can become entangled, and animals often mistake

it for food and end up starving to death with stomachs full of plastic.

Ocean plastics

that do not end up asphyxiating an albatross or entangling an elephant seal

eventually break down into microplastics, which penetrate every branch of the

food web and are nearly impossible to remove from the environment.

One thing

everyone agrees on is that we need to stop the flow of plastic into the ocean.

“We need to turn

off the tap,” Lecomte said.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_509089081')

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_552628228')

Read More

The first edition of the Billboard Arabia Music Awards will present more than 40 prestigious awards, based on listenership data, and will be attended by renowned and rising stars.

The toxin that helps oyster mushrooms devour worm flesh

Today's Horoscopes

In 2019, French swimmer Benoit Lecomte swam more than 300

nautical miles through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch to raise awareness about

marine plastic pollution.

As he swam, he was often surprised to find that he was not alone.

“Every time I saw plastic debris floating, there was life all around it,” Lecomte said.

The patch was less a garbage island than a garbage soup of plastic bottles, fishing nets, tires and toothbrushes. And floating at its surface were blue dragon nudibranchs, Portuguese man-o-wars and other small surface-dwelling animals, which are collectively known as neuston.

Scientists aboard the ship supporting Lecomte’s swim systematically sampled the patch’s surface waters. The team found that there were much higher concentrations of neuston within the patch than outside it. In some parts of the patch, there were nearly as many neuston as pieces of plastic.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the blue button Porpita species, viewed from above.

“I had this hypothesis that gyres concentrate life and plastic in similar ways, but it was still really surprising to see just how much we found out there,” said Rebecca Helm, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina and co-author of the study. “The density was really staggering. To see them in that concentration was like, wow.”

The findings were posted last month on bioRxiv and have not yet been subjected to peer review. But if they hold up, Helm and other scientists say, it may complicate efforts by conservationists to remove the immense and ever-growing amount of plastic in the patch.

The world’s oceans contain five gyres, large systems of circular currents powered by global wind patterns and forces created by Earth’s rotation. They act like enormous whirlpools, so anything floating within one will eventually be pulled into its center. For nearly a century, floating plastic waste has been pouring into the gyres, creating an assortment of garbage patches. The largest, the Great Pacific Patch, is halfway between Hawaii and California and contains at least 79,000 tons of plastic, according to the Ocean Cleanup Foundation. All that trash turns out to be a great foothold for living things.

Helm and her colleagues pulled many individual creatures out of the sea with their nets: by-the-wind sailors, free-floating hydrozoans that travel on ocean breezes; blue buttons, quarter-sized cousins of the jellyfish; and violet sea-snails, which build “rafts” to stay afloat by trapping air bubbles in a soaplike mucus they secrete from a gland in their foot. They also found potential evidence that these creatures may be reproducing within the patch.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the snail Recluzia species, viewed from the side oral end.

“I wasn’t surprised,” said Andre Boustany, a researcher with the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California. “We know this place is an aggregation area for drifting plastics, so why would it not be an aggregation area for these drifting animals as well?”

Little is known about neuston, especially those found far from land in the heart of ocean gyres.

“They are very difficult to study because they occur in the open ocean and you cannot collect them unless you go on marine expeditions, which cost a lot of money,” said Lanna Cheng, a research scientist at the University of California, San Diego.

Because so little is known about the life history and ecology of these creatures, this study, though severely limited in size and scope, offers valuable insights to scientists.

But Helm said there is another implication of the study: Organizations working to remove plastic waste from the patch may also need to consider what the study means for their efforts.

There are several nonprofit organizations working to remove floating plastic from the Great Pacific Patch. The largest, the Ocean Cleanup Foundation in the Netherlands, developed a net specifically to collect and concentrate marine debris as it is pulled across the sea’s surface by winds and currents. Once the net is full, a ship takes its contents to land for proper disposal.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows a buoy barnacle, Dosima fascicularis, viewed from the side, with aboral white float at the water’s surface.

Helm and other scientists warn that such nets threaten sea life, including neuston. Although adjustments to the net’s design have been made to reduce bycatch, Helm believes any large-scale removal of plastic from the patch could pose a threat to its neuston inhabitants.

“When it comes to figuring out what to do about the plastic that’s already in the ocean, I think we need to be really careful,” she said. The results of her study “really emphasize the need to study the open ocean before we try to manipulate it, modify it, clean it up or extract minerals from it.”

Laurent Lebreton, an oceanographer with the Ocean Cleanup Foundation, disagreed with Helm.

“It’s too early to reach any conclusions on how we should react to that study,” he said. “You have to take into account the effects of plastic pollution on other species. We are collecting several tons of plastic every week with our system — plastic that is affecting the environment.”

Plastic in the ocean poses a threat to marine life, killing more than 1 million seabirds every year, as well as more than 100,000 marine mammals, according to UNESCO. Everything from fish to whales can become entangled, and animals often mistake it for food and end up starving to death with stomachs full of plastic.

Ocean plastics that do not end up asphyxiating an albatross or entangling an elephant seal eventually break down into microplastics, which penetrate every branch of the food web and are nearly impossible to remove from the environment.

One thing everyone agrees on is that we need to stop the flow of plastic into the ocean.

“We need to turn off the tap,” Lecomte said.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News

As he swam, he was often surprised to find that he was not alone.

“Every time I saw plastic debris floating, there was life all around it,” Lecomte said.

The patch was less a garbage island than a garbage soup of plastic bottles, fishing nets, tires and toothbrushes. And floating at its surface were blue dragon nudibranchs, Portuguese man-o-wars and other small surface-dwelling animals, which are collectively known as neuston.

Scientists aboard the ship supporting Lecomte’s swim systematically sampled the patch’s surface waters. The team found that there were much higher concentrations of neuston within the patch than outside it. In some parts of the patch, there were nearly as many neuston as pieces of plastic.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the blue button Porpita species, viewed from above.

“I had this hypothesis that gyres concentrate life and plastic in similar ways, but it was still really surprising to see just how much we found out there,” said Rebecca Helm, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina and co-author of the study. “The density was really staggering. To see them in that concentration was like, wow.”

The findings were posted last month on bioRxiv and have not yet been subjected to peer review. But if they hold up, Helm and other scientists say, it may complicate efforts by conservationists to remove the immense and ever-growing amount of plastic in the patch.

The world’s oceans contain five gyres, large systems of circular currents powered by global wind patterns and forces created by Earth’s rotation. They act like enormous whirlpools, so anything floating within one will eventually be pulled into its center. For nearly a century, floating plastic waste has been pouring into the gyres, creating an assortment of garbage patches. The largest, the Great Pacific Patch, is halfway between Hawaii and California and contains at least 79,000 tons of plastic, according to the Ocean Cleanup Foundation. All that trash turns out to be a great foothold for living things.

Helm and her colleagues pulled many individual creatures out of the sea with their nets: by-the-wind sailors, free-floating hydrozoans that travel on ocean breezes; blue buttons, quarter-sized cousins of the jellyfish; and violet sea-snails, which build “rafts” to stay afloat by trapping air bubbles in a soaplike mucus they secrete from a gland in their foot. They also found potential evidence that these creatures may be reproducing within the patch.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows the snail Recluzia species, viewed from the side oral end.

“I wasn’t surprised,” said Andre Boustany, a researcher with the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California. “We know this place is an aggregation area for drifting plastics, so why would it not be an aggregation area for these drifting animals as well?”

Little is known about neuston, especially those found far from land in the heart of ocean gyres.

“They are very difficult to study because they occur in the open ocean and you cannot collect them unless you go on marine expeditions, which cost a lot of money,” said Lanna Cheng, a research scientist at the University of California, San Diego.

Because so little is known about the life history and ecology of these creatures, this study, though severely limited in size and scope, offers valuable insights to scientists.

But Helm said there is another implication of the study: Organizations working to remove plastic waste from the patch may also need to consider what the study means for their efforts.

There are several nonprofit organizations working to remove floating plastic from the Great Pacific Patch. The largest, the Ocean Cleanup Foundation in the Netherlands, developed a net specifically to collect and concentrate marine debris as it is pulled across the sea’s surface by winds and currents. Once the net is full, a ship takes its contents to land for proper disposal.

A photo provided by Denis Rieck shows a buoy barnacle, Dosima fascicularis, viewed from the side, with aboral white float at the water’s surface.

Helm and other scientists warn that such nets threaten sea life, including neuston. Although adjustments to the net’s design have been made to reduce bycatch, Helm believes any large-scale removal of plastic from the patch could pose a threat to its neuston inhabitants.

“When it comes to figuring out what to do about the plastic that’s already in the ocean, I think we need to be really careful,” she said. The results of her study “really emphasize the need to study the open ocean before we try to manipulate it, modify it, clean it up or extract minerals from it.”

Laurent Lebreton, an oceanographer with the Ocean Cleanup Foundation, disagreed with Helm.

“It’s too early to reach any conclusions on how we should react to that study,” he said. “You have to take into account the effects of plastic pollution on other species. We are collecting several tons of plastic every week with our system — plastic that is affecting the environment.”

Plastic in the ocean poses a threat to marine life, killing more than 1 million seabirds every year, as well as more than 100,000 marine mammals, according to UNESCO. Everything from fish to whales can become entangled, and animals often mistake it for food and end up starving to death with stomachs full of plastic.

Ocean plastics that do not end up asphyxiating an albatross or entangling an elephant seal eventually break down into microplastics, which penetrate every branch of the food web and are nearly impossible to remove from the environment.

One thing everyone agrees on is that we need to stop the flow of plastic into the ocean.

“We need to turn off the tap,” Lecomte said.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News