Io, the third-largest of Jupiter’s

moons, is caught in a pressurized, explosive dance.

Orbiting near Ganymede and Europa, two of

the other largest Jovian moons, and the planet itself, Io’s mineral composition

is constantly pulled and pushed by gravity, creating frictional heat deep

inside the moon. This makes it extremely volcanically active — there are

hundreds of volcanoes and extensive networks of lava flows marking Io’s

surface.

“It’s being squeezed like an anger ball,”

said Jeff Morgenthaler, an astrophysicist at the Planetary Science Institute.

Despite a number of close-flying

spacecrafts over the past few decades — including the Voyager 1 and Galileo

missions — as well as constant observation from Earth, there are lasting

mysteries about the kind of volcanic activity on Io and how the moon’s fiery

energy interacts with Jupiter and other nearby bodies.

Last year, Morgenthaler, who studies gases

Io emits and the cloud these gases create around Jupiter, picked up signs that

a different kind of eruption — a more powerful or more persistent one — was

occurring.

“It’s an exciting observation,” said Ashley

Davies, a planetary scientist and volcanologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion

Laboratory who was not involved in Morgenthaler’s study. “It’s showing that Io

is certainly one of the most energetic bodies in the solar system, and you have

no idea how it’s going to appear when you turn your telescope on it.”

The observation could help to guide future

study of Io, including preparations for NASA’s Juno space probe, which has been

orbiting Jupiter since 2016 and is scheduled to fly only a couple hundred miles

from the Jovian moon this December.

Hot and coldBecause Io is far from the sun and has a

very thin atmosphere, its surface, on average, sits at around minus 130 degrees

Celsius, and it is coated in a frosty layer of sulfuric compounds. Volcanic

eruptions there, which come in many different forms and intensities, can reach

temperatures up to 1,370 degrees Celsius.

There are lasting mysteries about the kind of volcanic activity on Io and how the moon’s fiery energy interacts with Jupiter and other nearby bodiesWhen super hot meets super cold, molecules

like sulfur dioxide and sodium can be shot into space. Some of the most

explosive eruptions come from fissures in the surface and throw fountains of

lava nearly a kilometer into space. The charged molecules create what is known

as a “plasma torus” in Io’s wake: a doughnut-shaped cloud of ionized gas that

collects in Jupiter’s magnetic field.

It is possible to look directly at Io’s

volcanic hot spots with infrared telescopes. However, since 2017, Morgenthaler

has taken a different approach, focusing on the moon’s plasma torus through the

Planetary Science Institute’s Io Input/Output observatory (IoIO), in Arizona.

Instead of using infrared light, Morgenthaler uses IoIO to block light from

Jupiter and measure the gas around it.

Reading the eruptionsDavies said that while infrared telescopes

can tell us where volcanoes are erupting on Io and how powerful they may be,

studying the plasma torus can tell us when an eruption is chemically rich —

signaling that it may be more powerful, more persistent, or just more peculiar.

One eruption could push more ionized gas into the torus. Another could send out

a lot of neutral gas. “It doesn’t happen every time, and it’s an interesting

link,” Davies said.

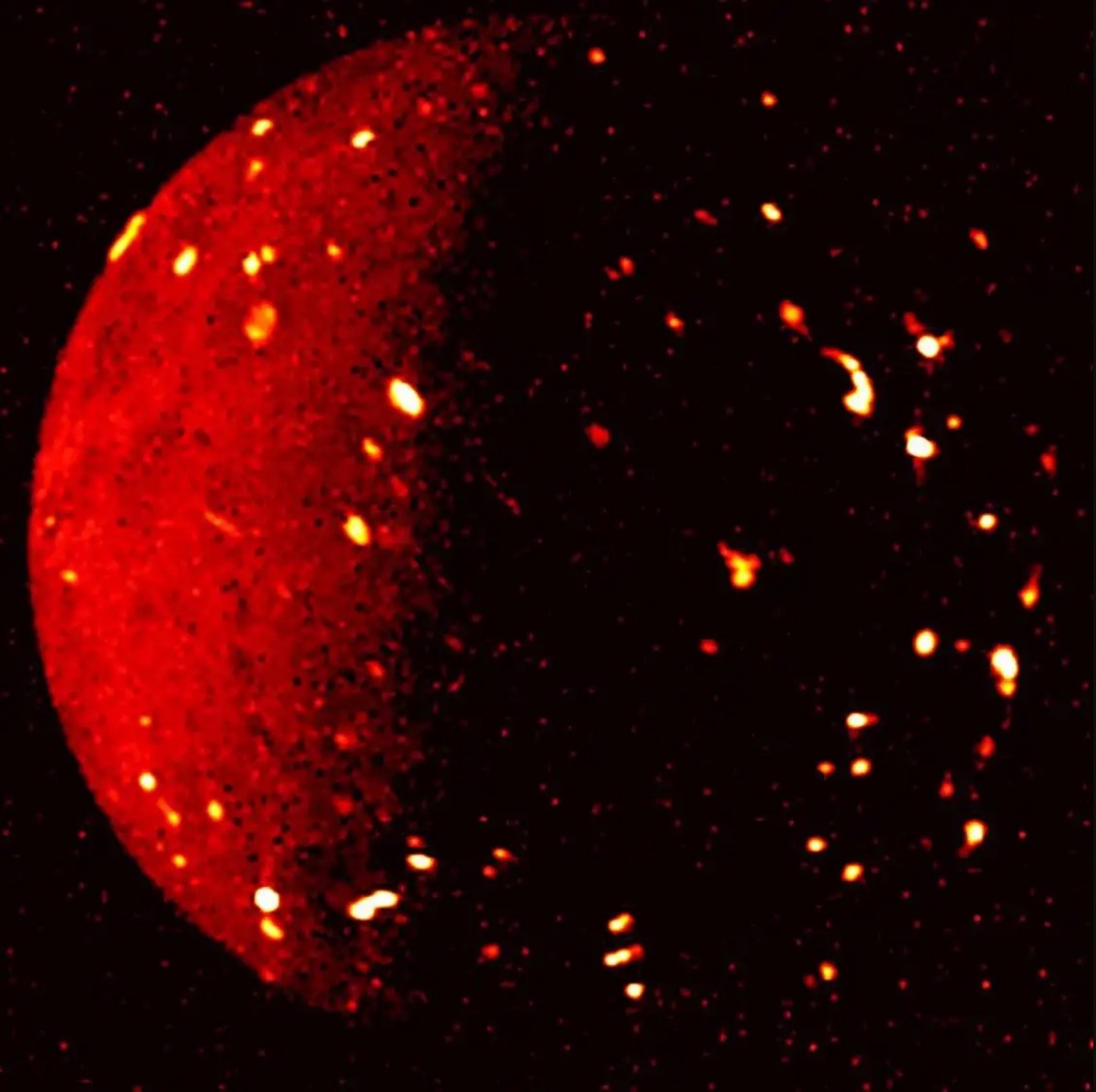

Io,

a moon of Jupiter, captured by the Juno spacecraft as it flew by on July 5,

2022.

Each year Morgenthaler has monitored

volcanic activity through IoIO, he has noticed some kind of increased

concentration, or brightening, of gases in the plasma torus. These changes

correlate with volcanic outbursts, the intensities of which can be measured by

the levels of sodium emitted from the moon. But, from September through

December 2022, after a large volcanic outburst, he noticed that the torus

contained much less sulfur dioxide than the size of the eruption would suggest.

The torus was not as bright as it should have been.

This could mean that the eruption had a

different chemical composition from the others, or that different kinds of

minerals had been disturbed. It would be like Mount St. Helens, a steep

stratovolcano that can erupt explosively, sending dirt, rock, and sodium into

the atmosphere, erupting on Earth, rather than Mauna Loa, a gently-sloped

shield volcano that erupts with liquid lava flows. Or it could mean that the

torus was rapidly diffusing in response to the intense eruption.

Studying the plasma torus can tell us when an eruption is chemically rich — signaling that it may be more powerful, more persistent, or just more peculiarMore than anything, Morgenthaler said, it

is a call for more research.

“I’m just raising the flag, and saying,

‘This has happened,’ ” Morgenthaler said after announcing the observation this

month.

What is next in Io observation?Studying the anomaly might draw out, in

better detail, the different kinds of volcanoes on Io, as well as the

interactions between the plasma torus and other massive moons around Jupiter.

However, much more data will have to be gathered to put all the pieces

together, including from other powerful telescopes on Earth, like the James

Webb Space Telescope, as well as from the Juno space probe.

For the moment, to study gases from Io,

Morgenthaler said that his method, which is cheap and could be adapted by small

research organizations and even some backyard astronomers, is often

underutilized. But his work may open the door for similar and widespread

research that could provide data to help understand the Jovian system.

Davies said that this kind of piecemeal

research is integral to understanding Io. “You can think of it like looking at

different parts of an elephant,” he said.

The fact that Morgenthaler’s most recent

observation was made with largely accessible instruments opens the possibility

of more studies, similar and different, in kind. “The more monitoring we can

get, the better it will be,” Davies said.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_509089081')

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_552628228')

Read More

Suspicious Behavior Sparks Panic: Is ChatGPT Watching Us?

Platform “X” Plans to Phase Out Direct Messaging System

Google and Samsung to Launch “Android XR” Smart Glasses

Io, the third-largest of Jupiter’s

moons, is caught in a pressurized, explosive dance.

Orbiting near Ganymede and Europa, two of

the other largest Jovian moons, and the planet itself, Io’s mineral composition

is constantly pulled and pushed by gravity, creating frictional heat deep

inside the moon. This makes it extremely volcanically active — there are

hundreds of volcanoes and extensive networks of lava flows marking Io’s

surface.

“It’s being squeezed like an anger ball,”

said Jeff Morgenthaler, an astrophysicist at the Planetary Science Institute.

Despite a number of close-flying

spacecrafts over the past few decades — including the Voyager 1 and Galileo

missions — as well as constant observation from Earth, there are lasting

mysteries about the kind of volcanic activity on Io and how the moon’s fiery

energy interacts with Jupiter and other nearby bodies.

Last year, Morgenthaler, who studies gases

Io emits and the cloud these gases create around Jupiter, picked up signs that

a different kind of eruption — a more powerful or more persistent one — was

occurring.

“It’s an exciting observation,” said Ashley

Davies, a planetary scientist and volcanologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion

Laboratory who was not involved in Morgenthaler’s study. “It’s showing that Io

is certainly one of the most energetic bodies in the solar system, and you have

no idea how it’s going to appear when you turn your telescope on it.”

The observation could help to guide future

study of Io, including preparations for NASA’s Juno space probe, which has been

orbiting Jupiter since 2016 and is scheduled to fly only a couple hundred miles

from the Jovian moon this December.

Hot and coldBecause Io is far from the sun and has a

very thin atmosphere, its surface, on average, sits at around minus 130 degrees

Celsius, and it is coated in a frosty layer of sulfuric compounds. Volcanic

eruptions there, which come in many different forms and intensities, can reach

temperatures up to 1,370 degrees Celsius.

There are lasting mysteries about the kind of volcanic activity on Io and how the moon’s fiery energy interacts with Jupiter and other nearby bodies

When super hot meets super cold, molecules

like sulfur dioxide and sodium can be shot into space. Some of the most

explosive eruptions come from fissures in the surface and throw fountains of

lava nearly a kilometer into space. The charged molecules create what is known

as a “plasma torus” in Io’s wake: a doughnut-shaped cloud of ionized gas that

collects in Jupiter’s magnetic field.

It is possible to look directly at Io’s

volcanic hot spots with infrared telescopes. However, since 2017, Morgenthaler

has taken a different approach, focusing on the moon’s plasma torus through the

Planetary Science Institute’s Io Input/Output observatory (IoIO), in Arizona.

Instead of using infrared light, Morgenthaler uses IoIO to block light from

Jupiter and measure the gas around it.

Reading the eruptionsDavies said that while infrared telescopes

can tell us where volcanoes are erupting on Io and how powerful they may be,

studying the plasma torus can tell us when an eruption is chemically rich —

signaling that it may be more powerful, more persistent, or just more peculiar.

One eruption could push more ionized gas into the torus. Another could send out

a lot of neutral gas. “It doesn’t happen every time, and it’s an interesting

link,” Davies said.

Io,

a moon of Jupiter, captured by the Juno spacecraft as it flew by on July 5,

2022.

Io,

a moon of Jupiter, captured by the Juno spacecraft as it flew by on July 5,

2022.

Each year Morgenthaler has monitored

volcanic activity through IoIO, he has noticed some kind of increased

concentration, or brightening, of gases in the plasma torus. These changes

correlate with volcanic outbursts, the intensities of which can be measured by

the levels of sodium emitted from the moon. But, from September through

December 2022, after a large volcanic outburst, he noticed that the torus

contained much less sulfur dioxide than the size of the eruption would suggest.

The torus was not as bright as it should have been.

This could mean that the eruption had a

different chemical composition from the others, or that different kinds of

minerals had been disturbed. It would be like Mount St. Helens, a steep

stratovolcano that can erupt explosively, sending dirt, rock, and sodium into

the atmosphere, erupting on Earth, rather than Mauna Loa, a gently-sloped

shield volcano that erupts with liquid lava flows. Or it could mean that the

torus was rapidly diffusing in response to the intense eruption.

Studying the plasma torus can tell us when an eruption is chemically rich — signaling that it may be more powerful, more persistent, or just more peculiar

More than anything, Morgenthaler said, it

is a call for more research.

“I’m just raising the flag, and saying,

‘This has happened,’ ” Morgenthaler said after announcing the observation this

month.

What is next in Io observation?Studying the anomaly might draw out, in

better detail, the different kinds of volcanoes on Io, as well as the

interactions between the plasma torus and other massive moons around Jupiter.

However, much more data will have to be gathered to put all the pieces

together, including from other powerful telescopes on Earth, like the James

Webb Space Telescope, as well as from the Juno space probe.

For the moment, to study gases from Io,

Morgenthaler said that his method, which is cheap and could be adapted by small

research organizations and even some backyard astronomers, is often

underutilized. But his work may open the door for similar and widespread

research that could provide data to help understand the Jovian system.

Davies said that this kind of piecemeal

research is integral to understanding Io. “You can think of it like looking at

different parts of an elephant,” he said.

The fact that Morgenthaler’s most recent

observation was made with largely accessible instruments opens the possibility

of more studies, similar and different, in kind. “The more monitoring we can

get, the better it will be,” Davies said.

Read more Lifestyle

Jordan News