When Apple introduced the Macintosh in 1984, it was

the dawn of an era. Personal computing was ascendant. The World Wide Web was on

its way. Screens would soon begin to take over people’s lives — an early

precursor to the always-on, Zoom-to-Zoom world we’re living in today.

Men, especially ones named Steve and Bill, get a lot of

credit for heralding this modern era of information technology. But behind the

scenes, at tech and design firms around the world, the look and feel of those

screens was defined by lesser-known graphic designers — people who created the

windows, dialogue boxes and icons taken largely for granted these days.

Susan Kare, for instance, made the original icons, graphic

elements and fonts for the Macintosh operating system: the smiling Mac, the

trash can, the system-error bomb. And though the industry was predominantly

male, she had many woman peers — among them Loretta Staples, an interface designer

in San Francisco.

For seven years, she dreamed up interactive experiences

meant to delight and satisfy the end user. That was long before “design

thinking” became the talk of Silicon Valley, before her domain was sleekly

rebranded as U.I. When she started, the field was so nascent that most of the

software didn’t exist.

“It was just so exciting,” Staples said during a Zoom call

in December. “You had to put stuff together and fashion your own tools and ways

of making things.”

Now 67, living in Connecticut and working as a therapist

(the fifth phase of her professional life), she sees those years as formative,

not only for her creativity but her worldview.

The Call of California

Staples grew up in the late v60s reading The Village Voice

on a military base in Kentucky, dreaming of life in the Northeast. But after

completing her studies in art history at Yale University and graphic design at

the Rhode Island School of Design, she began to question what she had come to

see as regional values.

One of her professors, Inge Druckrey, was recognized for

bringing Swiss modernism to American schools. Also known as the International

Style, it is visually defined by rigid grids and sans serif typefaces. The

designer is meant to be “invisible.” New York City’s subway signs and

Volkswagen’s “Lemon” ad are good examples of its manifestation in American

culture.

Staples valued the visual authority and logic behind this

school of thought but found its fundamental neutrality confusing. “Here I am,

first-generation, middle-class, half-Black, half-Japanese, was never going to

go to college and somehow weirdly ended up at Yale,” she said. “What on Earth

does all this stuff have to do with ‘where I come from,’ whatever even that

is?”

She also found that institutions in the Northeast were

dismissive of rapidly evolving digital tools. “I would keep scratching my head

wondering, ‘When is the East Coast going to get how important all this stuff

is?’” Staples said.

So, in 1988, she responded to a newspaper ad for the

Understanding Business, or TUB, a design studio in San Francisco run by Richard

Saul Wurman, a graphic designer known today for creating TED conferences. At

the time, TUB was one of the largest studios focused on Macintosh computers.

Staples taught herself how to use a beta version of Adobe

Photoshop and other new tools that would allow her to design for interaction.

Because the field was still emerging, she often “kludged” different programs

together to get her desired effect.

“In some ways, it was a more diverse world,” she said. “It

wasn’t this unified, pervasive World Wide Web browser app kind of thing.”

UI and U dot I

Staples became a full-time interface designer in 1989. She

worked for noted designer Clement Mok, briefly under John Sculley’s leadership

at Apple, then opened her own studio, U dot I, in 1992.

“We take it for granted because UI is a big, big deal now,”

said Maria Giudice, who worked with Staples at TUB and has remained a friend.

“But she was one of the few people who was really working in that space.”

Interface design was full of thoughtful little innovations

and touches of magic, like hovering a cursor over a blurry object to bring it

into focus. “I know that probably doesn’t sound like much now, but at the time

it took a lot to make that happen,” Staples said.

Icons, though limited to a meager dollop of chunky pixels,

were also a place for customization. Using ResEdit, a programmer’s software,

she once constructed an icon of a ceramic coffee mug with a tiny doughnut

nestled against it. “It even had a little shading,” she said.

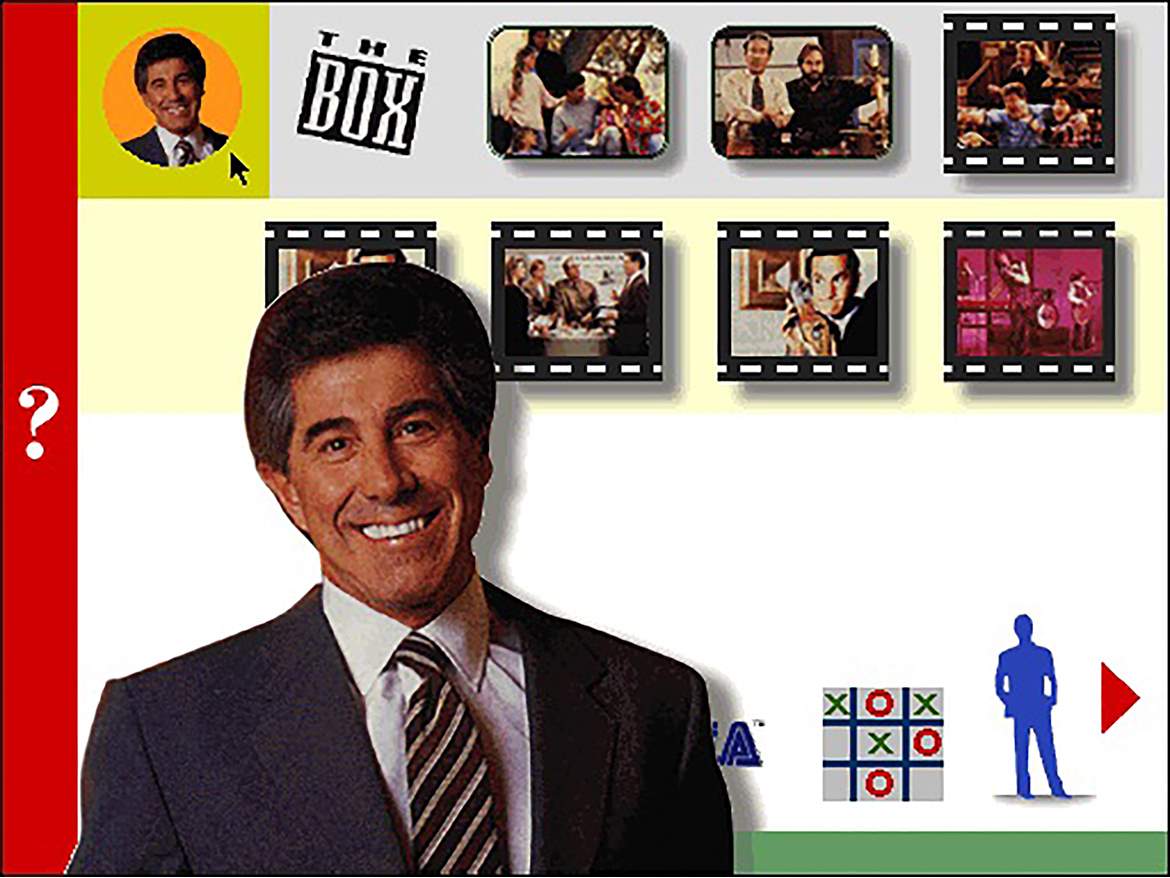

In an undated image provided via Loretta Staples, Part of the interactive TV prototype Loretta Staples worked on for Paramount/Viacom. Staples, a user interface designer in the 1980s and ’90s, had a front-row seat to the rise of personal computing. (Photo: NYTimes)

Her clients in the ’90s included AT&T, the Smithsonian

Institution, Sony and Paramount/Viacom, where she helped create a design for an

interactive television prototype (a forerunner, in many ways, to streaming TV).

Meanwhile, the World Wide Web was erupting. “For me, the

internet was the beginning of the end,” Staples said. When she began working as

an interface designer six years prior, graphical user interface wasn’t widely

understood; now webpages were popping up by the hundreds, and everyone was

surfing the net. Everything was becoming more standardized, commercialized,

crowded and boring.

A Designer for Life

In a letter to the editor published both in Adbusters, an

activist magazine, and Emigre, a graphic design magazine, Staples described

recoiling at a progressive political publication that was designed in an

expressive manner — a stark contrast to the increasingly homogeneous look of

the world in her own field at the turn of the millennium.

“I’ve been viscerally programmed to respond predictably to

graphic conventions,” she wrote. “Could it be that increasingly graphic design

is less the solution and more the problem?”

“I felt like I recognized design as a particular kind of

cultural practice that I didn’t want to practice anymore,” Staples said.

After making an exit, she cycled agilely through

professions: design educator (her essays, which documented a pivotal period in

digital design, are still used in classrooms today), fine artist, online

business consultant. In 2000, she moved from Michigan, where she was teaching

design, to New York City, disposing of a basement’s worth of work documents in

the process.

“I’m not an archivist ultimately,” she said. “Things come

and go, and that’s the way my life has been.” Her website, however, contains a

selection of artifacts from her early professional life: 12 images of her

designs, plus the student work and syllabuses for classes she taught.

Looking back, Staples said that she used to see herself as a

cultural critic disguised as a designer; now she’s a cultural critic disguised

as a therapist — one who has spent the last year working exclusively over video

conferencing.

“It’s weird to have the option to control a view,” she said.

“Not everyone is looking at the same thing.”

“She’s still thinking like a designer,” Giudice said, “just

applying it in a different way.”

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_509089081')

(window.globalAmlAds = window.globalAmlAds || []).push('admixer_async_552628228')

Read More

Google Announces: 350 Million Monthly Users for Gemini

Elon Musk Makes Major Moves with New Changes on "X"

Suspicious Behavior Sparks Panic: Is ChatGPT Watching Us?

When Apple introduced the Macintosh in 1984, it was

the dawn of an era. Personal computing was ascendant. The World Wide Web was on

its way. Screens would soon begin to take over people’s lives — an early

precursor to the always-on, Zoom-to-Zoom world we’re living in today.

Men, especially ones named Steve and Bill, get a lot of

credit for heralding this modern era of information technology. But behind the

scenes, at tech and design firms around the world, the look and feel of those

screens was defined by lesser-known graphic designers — people who created the

windows, dialogue boxes and icons taken largely for granted these days.

Susan Kare, for instance, made the original icons, graphic

elements and fonts for the Macintosh operating system: the smiling Mac, the

trash can, the system-error bomb. And though the industry was predominantly

male, she had many woman peers — among them Loretta Staples, an interface designer

in San Francisco.

For seven years, she dreamed up interactive experiences

meant to delight and satisfy the end user. That was long before “design

thinking” became the talk of Silicon Valley, before her domain was sleekly

rebranded as U.I. When she started, the field was so nascent that most of the

software didn’t exist.

“It was just so exciting,” Staples said during a Zoom call

in December. “You had to put stuff together and fashion your own tools and ways

of making things.”

Now 67, living in Connecticut and working as a therapist

(the fifth phase of her professional life), she sees those years as formative,

not only for her creativity but her worldview.

The Call of California

Staples grew up in the late v60s reading The Village Voice

on a military base in Kentucky, dreaming of life in the Northeast. But after

completing her studies in art history at Yale University and graphic design at

the Rhode Island School of Design, she began to question what she had come to

see as regional values.

One of her professors, Inge Druckrey, was recognized for

bringing Swiss modernism to American schools. Also known as the International

Style, it is visually defined by rigid grids and sans serif typefaces. The

designer is meant to be “invisible.” New York City’s subway signs and

Volkswagen’s “Lemon” ad are good examples of its manifestation in American

culture.

Staples valued the visual authority and logic behind this

school of thought but found its fundamental neutrality confusing. “Here I am,

first-generation, middle-class, half-Black, half-Japanese, was never going to

go to college and somehow weirdly ended up at Yale,” she said. “What on Earth

does all this stuff have to do with ‘where I come from,’ whatever even that

is?”

She also found that institutions in the Northeast were

dismissive of rapidly evolving digital tools. “I would keep scratching my head

wondering, ‘When is the East Coast going to get how important all this stuff

is?’” Staples said.

So, in 1988, she responded to a newspaper ad for the

Understanding Business, or TUB, a design studio in San Francisco run by Richard

Saul Wurman, a graphic designer known today for creating TED conferences. At

the time, TUB was one of the largest studios focused on Macintosh computers.

Staples taught herself how to use a beta version of Adobe

Photoshop and other new tools that would allow her to design for interaction.

Because the field was still emerging, she often “kludged” different programs

together to get her desired effect.

“In some ways, it was a more diverse world,” she said. “It

wasn’t this unified, pervasive World Wide Web browser app kind of thing.”

UI and U dot I

Staples became a full-time interface designer in 1989. She

worked for noted designer Clement Mok, briefly under John Sculley’s leadership

at Apple, then opened her own studio, U dot I, in 1992.

“We take it for granted because UI is a big, big deal now,”

said Maria Giudice, who worked with Staples at TUB and has remained a friend.

“But she was one of the few people who was really working in that space.”

Interface design was full of thoughtful little innovations

and touches of magic, like hovering a cursor over a blurry object to bring it

into focus. “I know that probably doesn’t sound like much now, but at the time

it took a lot to make that happen,” Staples said.

Icons, though limited to a meager dollop of chunky pixels,

were also a place for customization. Using ResEdit, a programmer’s software,

she once constructed an icon of a ceramic coffee mug with a tiny doughnut

nestled against it. “It even had a little shading,” she said.

In an undated image provided via Loretta Staples, Part of the interactive TV prototype Loretta Staples worked on for Paramount/Viacom. Staples, a user interface designer in the 1980s and ’90s, had a front-row seat to the rise of personal computing. (Photo: NYTimes)

Her clients in the ’90s included AT&T, the Smithsonian

Institution, Sony and Paramount/Viacom, where she helped create a design for an

interactive television prototype (a forerunner, in many ways, to streaming TV).

Meanwhile, the World Wide Web was erupting. “For me, the

internet was the beginning of the end,” Staples said. When she began working as

an interface designer six years prior, graphical user interface wasn’t widely

understood; now webpages were popping up by the hundreds, and everyone was

surfing the net. Everything was becoming more standardized, commercialized,

crowded and boring.

A Designer for Life

In a letter to the editor published both in Adbusters, an

activist magazine, and Emigre, a graphic design magazine, Staples described

recoiling at a progressive political publication that was designed in an

expressive manner — a stark contrast to the increasingly homogeneous look of

the world in her own field at the turn of the millennium.

“I’ve been viscerally programmed to respond predictably to

graphic conventions,” she wrote. “Could it be that increasingly graphic design

is less the solution and more the problem?”

“I felt like I recognized design as a particular kind of

cultural practice that I didn’t want to practice anymore,” Staples said.

After making an exit, she cycled agilely through

professions: design educator (her essays, which documented a pivotal period in

digital design, are still used in classrooms today), fine artist, online

business consultant. In 2000, she moved from Michigan, where she was teaching

design, to New York City, disposing of a basement’s worth of work documents in

the process.

“I’m not an archivist ultimately,” she said. “Things come

and go, and that’s the way my life has been.” Her website, however, contains a

selection of artifacts from her early professional life: 12 images of her

designs, plus the student work and syllabuses for classes she taught.

Looking back, Staples said that she used to see herself as a

cultural critic disguised as a designer; now she’s a cultural critic disguised

as a therapist — one who has spent the last year working exclusively over video

conferencing.

“It’s weird to have the option to control a view,” she said.

“Not everyone is looking at the same thing.”

“She’s still thinking like a designer,” Giudice said, “just

applying it in a different way.”