SAN FRANCISCO, United States — A few months ago, makers of computer chips seemed on top of the world.

اضافة اعلان

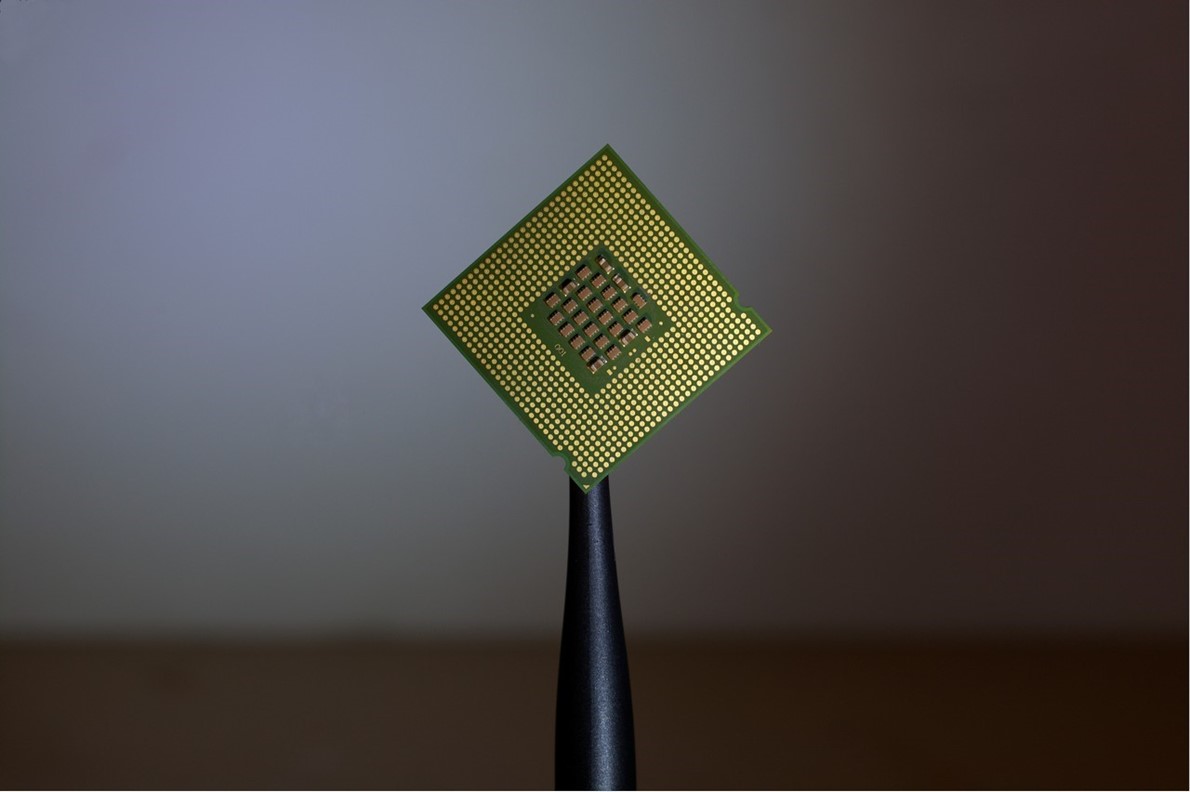

Customers could not get enough of the small slices

of silicon, which act as the brains of computers and are needed in just about

every device with an on-off switch. Demand was so strong — and

US dependence on

a foreign manufacturer so worrying — that Democrats and Republicans agreed in

July on a $52 billion subsidy package that included grants to build new chip

factories in America.

US chipmakers such as Intel, Micron Technology,

Texas Instruments and GlobalFoundries pledged huge expansions in domestic

manufacturing, betting on a growing need for their products and the prospects

of federal subsidies.

(Photos: Unsplash)

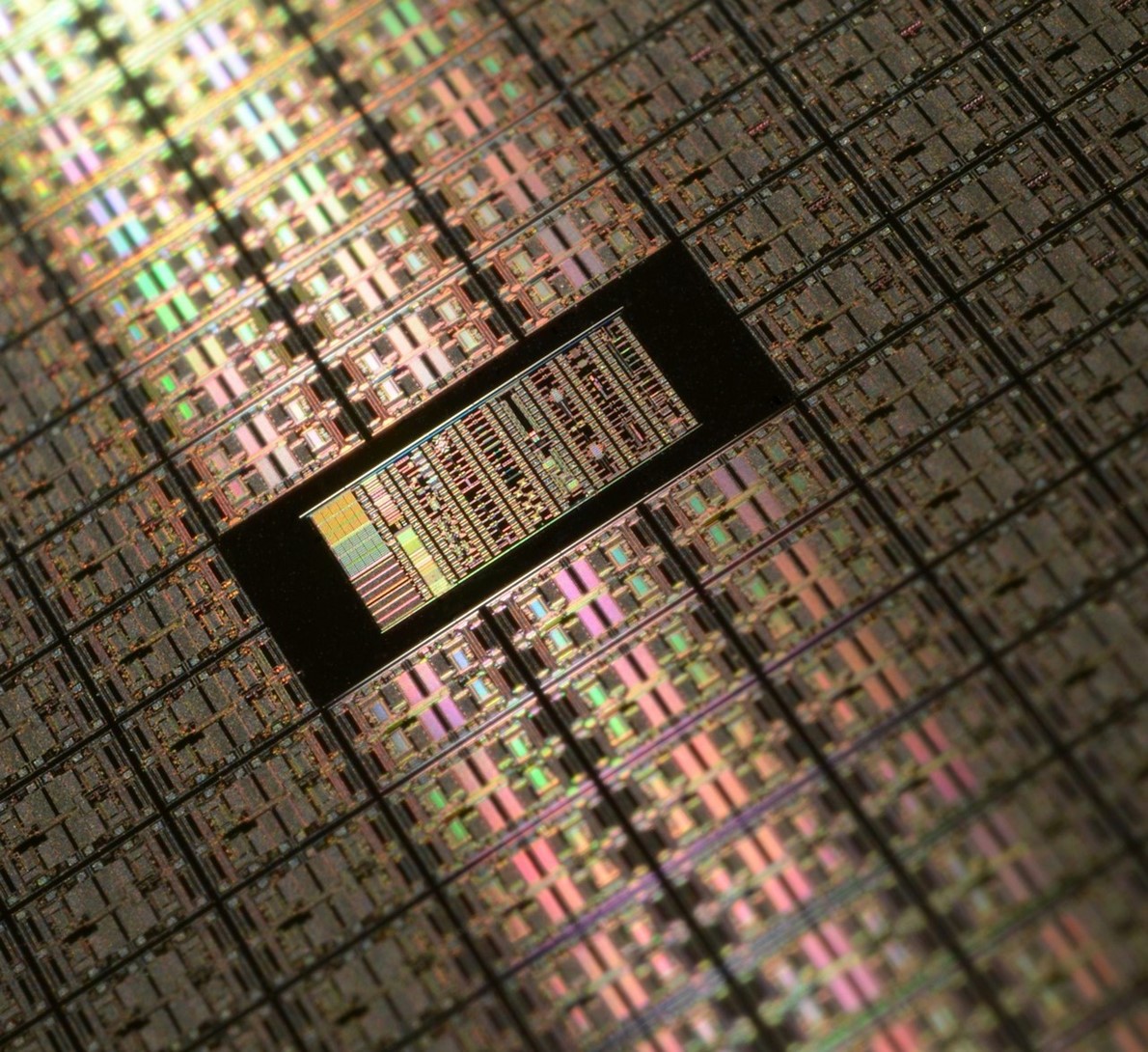

(Photos: Unsplash)

But lately, supplies of some semiconductors are

piling up, which could spell good news for consumers, but not for industry

executives. Their bold investment plans are running into a sudden and

unexpected slowdown in consumer demand for electronic gadgets, new US

restrictions on sales to customers in

China, rising inflation, and the unusual

prospect of a simultaneous shortage of some chips and a glut of others.

That has left chipmakers, which had been looking

ahead to immense demand and opportunity, suddenly grappling with immense

challenges. Many of the companies now face complex questions about whether and

when to boost production, amid uncertainty about how long the current sales

slowdown may last.

Fears of a slump, which have clobbered semiconductor stocks this year, are evident in recent earnings announcements from chipmakers.

“Six months ago, I would have said we were in this

hypergrowth phase,” said Rene Haas, CEO of Arm, the British company whose chip

technology powers billions of smartphones. Now, he said, “we’re in a pause.”

Fears of a slump, which have clobbered semiconductor

stocks this year, are evident in recent earnings announcements from chipmakers.

South Korea’s

SK Hynix on Wednesday reported a 20 percent drop in revenue and

said its business of memory chips “is facing an unprecedented deterioration in

market conditions.” Intel provided more evidence of a downturn in its

third-quarter results Thursday, including a 20 percent drop in revenue and a $664

million charge to cover cost-cutting measures expected to include job cuts.

The Biden administration delivered its own blow this

month with a sweeping set of restrictions aimed at hobbling China from using US

technology related to chips. The measures restrict sales of some advanced chips

to Chinese customers and prevent US companies from helping China develop some

kinds of chips.

That hurts semiconductor companies like Nvidia,

which makes graphics chips that are used to run AI applications in China and elsewhere.

The Silicon Valley company, already suffering from a sharp sales decline for

video game applications, recently estimated that the US restrictions would

probably reduce revenues in its current quarter by about $400 million.

The sanctions may bite even harder at companies that

sell chip-making equipment, which relied heavily in recent years on sales to

Chinese factories.

Lam Research, which produces tools that etch silicon

wafers to make chips, estimated that the China limitations would reduce its 2023

revenue by $2 billion to $2.5 billion. “We lost some very profitable customers

in the China region, and that’s going to persist,” Doug Bettinger, Lam’s chief

financial officer, said during an earnings call last week.

Applied Materials, the biggest maker of chip

manufacturing tools, also said sales would suffer because of the restrictions.

On Wednesday, another maker of chip manufacturing tools, KLA, said its revenue

next year was likely to shrink by $600 million to $900 million as it reduces

equipment sales and services to some customers in China.

Worries about foreign competition are nothing new in

semiconductors, an industry known for boom-and-bust cycles. But it has rarely

faced a player as potent as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., whose

factories on the island churn out chips designed by companies including Apple,

Amazon, Nvidia, and Qualcomm.

China claims

Taiwan as its own territory, creating a

potential risk to chip supplies. That helped drive the recent bipartisan

support for the US chip legislation, which was heavily pushed by President Joe

Biden.

The problem is particularly acute in processors and memory chips, which perform calculations and store data in personal computers, tablets, smartphones and other devices.

He trekked to Ohio last month for the groundbreaking

of a $20 billion Intel manufacturing campus. On Thursday, he visited a site

near

Syracuse, New York, where Micron has vowed to spend as much as $100

billion over 20 years on a large complex to build memory chips, a project he

called “one of the most significant investments in American history.”

Those plants will be needed at some point, industry

executives said. But they are now grappling with the sudden and sharp decline

in chip demand.

The problem is particularly acute in processors and

memory chips, which perform calculations and store data in personal computers,

tablets, smartphones and other devices.

Those products were hot commodities as consumers

worked from home during the coronavirus pandemic. But that boom has now cooled,

with PC sales dropping 15% in the third quarter, according to estimates by

International Data Corp. The research firm also predicted that smartphone sales

would fall 6.5 percent this year. Demand has been tempered by inflation as well

as a lengthy COVID lockdown in China, analysts said.

At the same time, inventories of chips piled up.

Computer makers spooked by the shortage bought more components than they ended

up needing, said Dan Hutcheson, a market researcher at the firm TechInsights.

When customer demand dried up, they started slashing orders.

“You see multiple issues converging,” said Syed

Alam, who leads Accenture’s global high-tech consulting practice, including

semiconductors.

Handel Jones, CEO at International Business

Strategies, predicts that total sales for the chip industry will still grow 9.5

percent this year. But he expects revenue to decline 3.4 percent to $584.5

billion next year. Last year, he had predicted steady yearly growth for the

chip industry from 2022 until 2030.

Warning signs included Intel’s second-quarter

results, which it announced in July. The company posted a rare loss and a 22

percent drop in revenue, blaming its own missteps and customers who cut chip

inventories.

At Micron, the mood also changed quickly. In May,

the company gave bullish presentations at an investor event in San Francisco

about long-term demand for its memory chips. By the next month, it was warning

of slowing demand and falling chip prices.

In September, the company reported a 20 percent drop in

fourth-quarter revenue. It also slashed planned spending on factories and

equipment by nearly 50 percent in the current fiscal year.

Read more Technology

Jordan News