My cat

is a bona fide chatterbox. Momo will meow when she is hungry and when she is

full, when she wants to be picked up and when she wants to be put down, when I

leave the room or when I enter it, or sometimes for what appears to be no real

reason at all.

اضافة اعلان

But because she

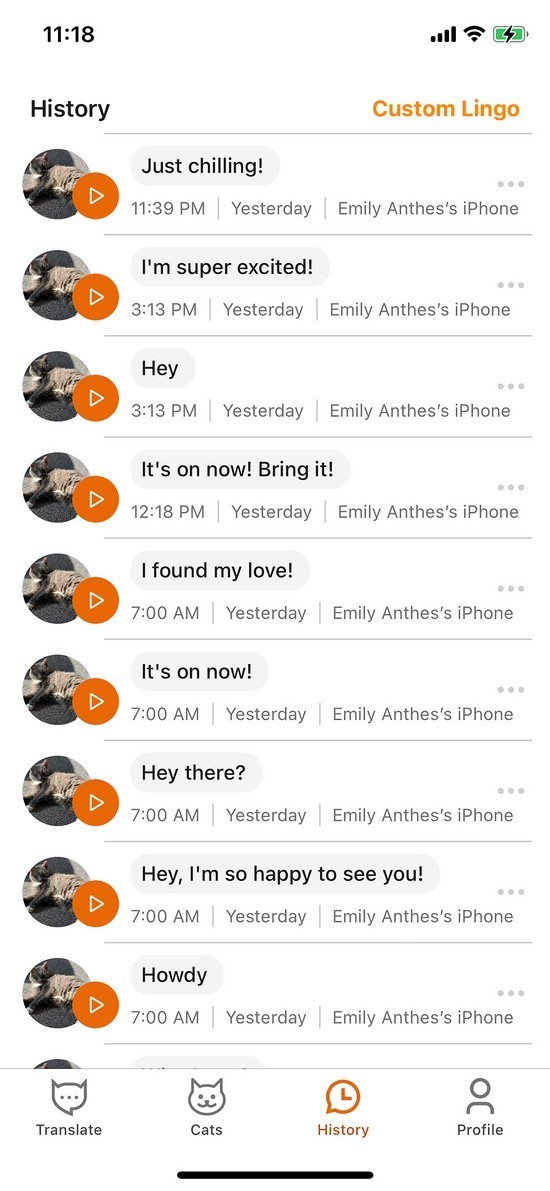

is a cat, she is also uncooperative. So the moment I downloaded

MeowTalk Cat Translator, a mobile app that promised to convert Momo’s meows into plain

English, she clammed right up. For two days I tried, and failed, to solicit a

sound.

New apps aim to give us an instant translation of what our pets’ sounds mean. (Photos: NYTimes)

New apps aim to give us an instant translation of what our pets’ sounds mean. (Photos: NYTimes)

On day three,

out of desperation, I decided to pick her up while she was wolfing down her

dinner, an interruption guaranteed to elicit a howl of protest. Right on cue,

Momo wailed. The app processed the sound, then played an advertisement for Sara

Lee, then rendered a translation: “I’m happy!”

I was dubious.

But MeowTalk provided a more plausible translation about a week later, when I

returned from a four-day trip. Upon seeing me, Momo meowed and then purred.

“Nice to see you,” the app translated. Then: “Let me rest.” (The ads

disappeared after I upgraded to a premium account.)

The urge to

converse with

animals is age-old, long predating the time when smartphones

became our best friends. Scientists have taught sign language to great apes,

chatted with grey parrots, and even tried to teach English to bottlenose

dolphins. Pets — with whom we share our homes but not a common language — are

particularly tempting targets. My TikTok feed brims with videos of Bunny, a

sheepadoodle who has learned to press sound buttons that play prerecorded phrases

such as “outside,” “scritches”, and “love you”.

MeowTalk is the

product of a growing interest in enlisting additional intelligences —

machine-learning algorithms — to decode animal communication. The idea is not

as far-fetched as it may seem. For example, machine-learning systems, which are

able to extract patterns from large data sets, can distinguish between the

squeaks that rodents make when they are happy and those that they emit when

they are in distress.

Applying the

same advances to our creature companions has obvious appeal.

“We’re trying to

understand what cats are saying and give them a voice,” said Javier Sanchez, a

founder of MeowTalk. “We want to use this to help people build better and

stronger relationships with their cats.”

To me, an animal

lover in a three-species household — Momo the cranky cat begrudgingly shares

space with Watson the overeager dog — the idea of a pet translation app was

tantalizing. But even MeowTalk’s creators acknowledge that there are still a

few kinks to work out.

Making meowsic

A meow contains multitudes. In the best of feline times — say, when a

cat is being fed — meows tend to be short and high-pitched and have rising

intonations, according to one recent study, which has not yet been published in

a

scientific journal. But in the worst of times (trapped in a cat carrier),

cats generally make their distress known with long, low-pitched meows that have

falling intonations.

“They tend to

use different types of melody in their meows when they try to signal different

things,” said Susanne Schötz, a phonetician at

Lund University in Sweden who

led the study as part of a research project called Meowsic.

MeowTalk uses the sounds it collects to refine its algorithms and improve its performance, the founders said, and pet owners can provide in-the-moment feedback if the app gets it wrong.

And in a 2019

study, Stavros Ntalampiras, a computer scientist at the University of Milan,

demonstrated that algorithms could automatically distinguish between the meows

that cats made in three situations: when being brushed, when waiting for food,

or when left alone in a strange environment.

MeowTalk, whose

founders enlisted Ntalampiras after the study appeared, expands on this

research, using algorithms to identify cat vocalizations made in a variety of

contexts.

The app detects

and analyzes cat utterances in real-time, assigning each one a broadly defined

“intent,” such as happy, resting, hunting, or “mating call”. It then displays a

conversational, plain English “translation” of whatever intent it detects, such

as Momo’s beleaguered “Let me rest”. (Oddly, none of these translations appear

to include “I will chew off your leg if you do not feed me this instant.”)

MeowTalk uses

the sounds it collects to refine its algorithms and improve its performance,

the founders said, and pet owners can provide in-the-moment feedback if the app

gets it wrong.

In 2021,

MeowTalk researchers reported that the software could distinguish among nine

intents with 90 percent accuracy overall. But the app was better at identifying

some than others, not infrequently confusing “happy” and “pain,” according to

the results.

And assessing

the accuracy of a cat translation app is tricky, said Sergei Dreizin, a

MeowTalk founder. “It’s assuming that you actually know what your cat wants,”

he said.

I found that the

app was, as advertised, especially good at detecting purring. (Then again, so

am I.) But it is much harder to determine what the calls in each category mean

— if they carry a consistent meaning at all — without actually having a way of,

you know, communicating with cats. (Cat-ch-22?)

After all, the

precise purpose of purring, which cats do in a wide variety of situations,

remains elusive. MeowTalk, however, interprets purrs as “resting”.

“But to be

candid,” Sanchez said, “it can mean. …” He rephrased: “We don’t know what it

means.”

Deciphering dogs

Dogs could soon have their own day. Zoolingua, a startup based in

Arizona, is hoping to create an artificial intelligence-powered dog translator

that will analyze canine vocalizations and body language.

Dog owners have

been overwhelmingly enthusiastic about the concept, said Con Slobodchikoff,

founder and CEO of Zoolingua, who spent much of his academic career studying

prairie dog communication. “Good communication between you and your dog means

having a great relationship with your dog,” he said. “And a lot of people want

a great relationship with their dog.”

(But, he added,

not everyone: “One small minority says, ‘I don’t think that I really want to

know what my dog is trying to communicate to me because maybe my dog doesn’t

like me.’”)

Still, even sop

histicated algorithms may miss critical real-world context and cues, said

Alexandra Horowitz, an expert on dog cognition at

Barnard College. For

instance, much of canine behavior is driven by scent. “How is that going to be

translated, when we don’t know the extent of it ourselves?” Horowitz said in an

email.

The desire to

understand what animals are “saying,” however, does not seem likely to abate.

The world can be a lonely place, especially so in the past few years. Finding

new ways to connect with other creatures, other species, can be a much needed

balm.

Personally, I

would pay at least two figures for an app that could help me know whether my

dog truly needs to go outside or just wants to see if the neighbor has put

bread out for the birds. (Maybe what I really need is a canine lie-detection

app.) For now, I will simply have to use my own judgment and powers of

observation.

After all, our pets are

already communicating with us all the time, Horowitz said. “It’s far more

interesting to me to learn my own dog’s communications,” she said, “especially

the idiosyncrasies that are formed between particular people and particular

animals, than pretend that an app can — presto! — translate it all.”

Read more Technology

Jordan News