SpaceX will be getting to the moon a bit more than a month from now, far

earlier than expected.

But it is all by accident, and it will cause a bit

of a mess.

اضافة اعلان

SpaceX, the rocket company started by

Elon Musk, has

been selected by NASA to provide the spaceship that will take its astronauts

back to the surface of the moon. That is still years away.

Instead, it is the 3.6-tonne upper stage of a SpaceX

rocket launched seven years ago that is to crash into the moon March 4, based

on recent observations and calculations by amateur astronomers.

Impact is predicted for 7:25am Eastern time, and

while there is still some uncertainty in the exact time and place, the rocket

piece is not going to miss the moon, said Bill Gray, developer of Project

Pluto, a suite of astronomical software used to calculate the orbits of

asteroids and comets.

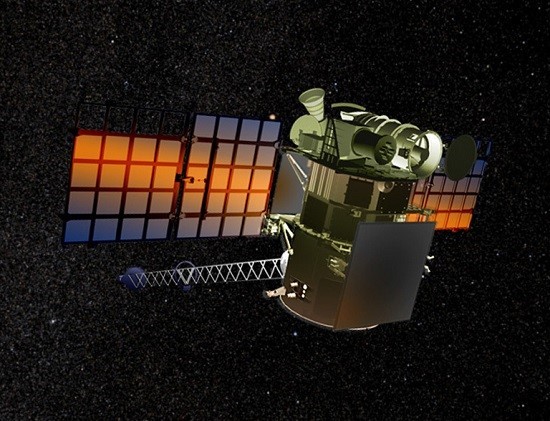

An artist’s concept of DSCOVR. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

An artist’s concept of DSCOVR. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

“It is quite certain it’s going to hit, and it will

hit within a few minutes of when it was predicted and probably within a few

kilometers,” Gray said.

Since the beginning of the Space Age, various

human-made artifacts have headed off into the solar system, not necessarily

expected to be seen again. That includes Musk’s Tesla Roadster, which was sent

on the first launch of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket in 2018 to an orbit passing

Mars. But sometimes they come back around, like in 2020 when a newly discovered

mystery object turned out to be part of a rocket launched in 1966 during NASA’s

Surveyor missions to the moon.

Gray has for years followed this particular piece of

SpaceX detritus, which helped launch the Deep Space Climate Observatory for the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on February 11, 2015.

That observatory, also known by the shortened name

DSCOVR, was headed to a spot about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth where it

can provide early warning of potentially destructive eruptions of energetic

particles from the sun.

DSCOVR was originally called Triana, an Earth

observation mission championed by Al Gore when he was vice president. The

spacecraft, derisively called GoreSat, was put into storage for years until it

was adapted for use as a solar storm warning system. Today it regularly

captures images of the whole of planet Earth from space, the original purpose

of Triana, including instances when the moon crosses in front of the planet.

Most of the time, the upper stage of a Falcon 9

rocket is pushed back into Earth’s atmosphere after it has delivered its

payload to orbit, a tidy way to avoid cluttering space.

But this upper stage needed all of its propellant to

send DSCOVR on its way to its distant destination, and it ended up in a very

high, elongated orbit around Earth, passing the orbit of the moon.

That opened the possibility of a collision someday.

The motion of the Falcon 9 stage, dead and uncontrolled, is determined

primarily by the gravitational pull of the Earth, the moon and the sun and a

nudge of pressure from sunlight.

Debris in low-Earth orbit is closely tracked because

of the danger to satellites and the International Space Station, but more

distant objects like the DSCOVR rocket are mostly forgotten.

“As far as I know, I am the only person tracking

these things,” Gray said.

While numerous spacecraft sent to the moon have

crashed there, this appears to be the first time that something from

Earth not

aimed at the moon will end up there.

On January 5, the rocket stage passed less than

10,000km from the moon. The moon’s gravity swung it on a course that looked

like it might later cross paths with the moon.

Gray put out a request to amateur astronomers to

take a look when the object zipped past Earth in January.

One of the people who answered the call was

Peter Birtwhistle, a retired information technology professional who lives about 80km

west of London. The domed 40cm telescope in his garden, grandly named the Great

Shefford Observatory, pointed at the part of the sky where the rocket stage

zipped past in a few minutes.

“This thing’s moving pretty fast,” Birtwhistle said.

The observations pinned down the trajectory enough

to predict an impact. Astronomers will have a chance to take one more look

before the rocket stage swings out beyond the moon one last time. It should

then come in to hit the far side of the moon, out of sight of anyone from

Earth.

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will not be in a

position to see the impact live. But it will later pass over the expected impact

site and take photographs of the freshly excavated crater.

Mark Robinson, a professor of earth and space

exploration at Arizona State University who serves as the principal

investigator for the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s camera, said he expected

3.6 tonnes of metal, hitting at a speed of some 2,500 meters of second, would

carve out a divot 10 to 20 meters wide, or up to 65 feet in diameter.

That will give scientists a look at what lies below

the surface, and unlike meteor strikes, they will know exactly the size and

time of the impact.

India’s Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft, also in orbit

around the moon, might also be able to photograph the impact site.

Other spacecraft headed toward the moon this year

might get a chance to spot the impact site — if they do not also end up making

unintended craters.

Read more Technology