So far it is been eye candy from heaven: The black

vastness of space teeming with enigmatic, unfathomably distant blobs of light.

Ghostly portraits of Neptune, Jupiter, and other neighbors we thought we knew.

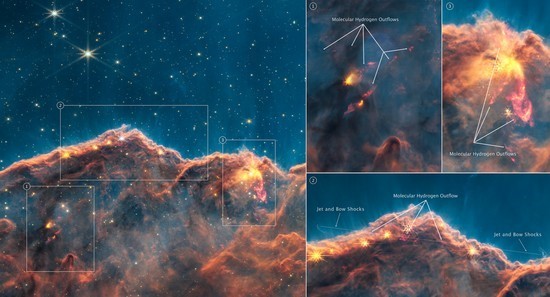

Nebulas and galaxies made visible by the penetrating infrared eyes of the James

Webb Space Telescope.

اضافة اعلان

The telescope, named for James Webb, the

NASA administrator

during the buildup to the Apollo moon landings, is a joint project of NASA, the

European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency. It was launched on

Christmas one year ago — after two trouble-plagued decades and $10 billion — on

a mission to observe the universe in wavelengths no human eye can see. With a

primary mirror 21 feet wide, the Webb is seven times as powerful as the Hubble

Space Telescope, its predecessor. Depending on how you do the accounting, one

hour of observing time on the telescope can cost NASA $19,000 or more.

But neither NASA nor the astronomers paid all that money and

political capital just for pretty pictures — not that anyone is complaining.

“The first images were just the beginning,” said Nancy Levenson, temporary

director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, which runs both the Webb and

the Hubble. “More is needed to turn them into real science.”

A bright (infrared) futureFor three days in December, some 200 astronomers filled an

auditorium at the institute to hear and discuss the first results from the

telescope. An additional 300 or so watched online, according to the organizers.

The event served as a belated celebration of Webb’s successful launch and

inauguration and a preview of its bright future.

One by one,

astronomers marched to the podium and, speaking

rapidly to obey the 12-minute limit, blitzed through a cosmos of discoveries:

Galaxies that, even in their relative youth, had already spawned huge black

holes. Atmospheric studies of some of the seven rocky exoplanets orbiting

Trappist 1, a red dwarf star that might harbor habitable planets. (Data

suggests that at least two of the exoplanets lack the bulky primordial hydrogen

atmospheres that would choke off life as we know it, but they may have skimpy

atmospheres of denser molecules such as water or carbon dioxide.)

Between presentations, on the sidelines, and in the hallways,

senior astronomers who were on hand in 1989 when the idea of the Webb telescope

was first broached congratulated one another and traded war stories about the

telescope’s development. They gasped audibly as the youngsters showed off data

that blew past their own achievements with the Hubble.

Jane Rigby,

project scientist for operations for the telescope,

recalled her emotional tumult a year ago as the telescope finally approached

its launch. The instrument had been designed to unfold in space — an intricate

process with 344 potential “single-point failures” — and Rigby could only count

them, over and over. “I was in the stage of denial,” she said in Baltimore. But

the launch and deployment went flawlessly. Now, she said, “I’m living the

dream.”

Garth Illingworth, an astronomer at the University of

California, Santa Cruz, who in 1989 chaired a key meeting at the Space

Telescope Science Institute that ultimately led to the Webb, said simply, “I’m

just blown away.”

At a reception after the first day of the meeting, John Mather

of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Webb’s senior project scientist from

the start, raised a glass to the 20,000 people who built the telescope, the 600

astronomers who had tested it in space and the new generation of scientists who

would use it.

“Some of you weren’t even born when we started planning for it,”

he said. “Have at it!”

Wayback machineThus far the telescope, bristling with cameras, spectroscopes,

and other instruments, is

exceeding expectations. (Its resolving power is twice

as good as advertised.) The telescope’s flawless launch, Rigby reported, has

left it with enough maneuvering fuel to keep it working for 26 years or more.

“These are happy numbers,” she said as she and her colleagues

rattled off performance statistics of their instruments. Rigby cautioned that

the telescope’s instruments were still being calibrated, so the numbers might

yet change.

Perhaps the biggest surprise from the telescope so far involves

events in the early millenniums of the universe. Galaxies appear to have been

forming, generating and nurturing stars faster than battle-tested cosmological

models estimated. “How did galaxies get so old so fast?” asked Adam Riess, a

Nobel physics laureate and cosmologist from Johns Hopkins University who

dropped in for the day.

Exploring that province — “cosmic spring,” as one astronomer

called it — is the goal of several international collaborations with snappy

acronyms like JADES (JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey), CEERS (Cosmic

Evolution Early Release Science), GLASS (Grism Lens-Amplified Survey From

Space) and PEARLS (Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing

Science).

Webb’s infrared vision is fundamental to these efforts. As the

universe expands, galaxies and other distant celestial objects are speeding

away from

Earth so fast that their light has been stretched and shifted to invisible,

infrared wavelengths. Beyond a certain point, the most distant galaxies are

receding so quickly, and their light is so stretched in wavelength, that they

are invisible even to the Hubble telescope.

The Webb telescope was designed to expose and explore these

regions, which represent the universe at just 1 billion years old, when the

first galaxies began to bloom with stars. “It takes time for matter to cool

down and get dense enough to ignite stars,” noted Emma Curtis-Lake, of the

University of Hertfordshire and a member of the JADES team. The rate of star

formation peaked when the universe was 4 billion years old, she added, and has

been falling ever since. The cosmos is now 13.8 billion years old.

In the closing talk, Mather limned the

telescope’s history, and

praised Barbara Mikulski, a former senator of Maryland, who supported the

project in 2011 when it was in danger of being canceled. He also previewed

NASA’s next big act: a 12-meter space telescope called the Habitable Worlds

Observatory that would seek out planets and study them.

“Everything that we did has turned out to be worth it,” he said.

“So we are here: This is a celebration party, getting a first peek at what’s

out here. It’s not the last thing we’re going to do.”

Read more Technology

Jordan News