The battery that flies

New York Times

last updated: Apr 18,2022

Kitty Hawk. The invention of the jet

engine. And on a frozen Vermont morning, circling above Lake Champlain, the

Alia.اضافة اعلان

In the mind of Christopher Caputo, a pilot, each moment signals a paradigm shift in aviation.

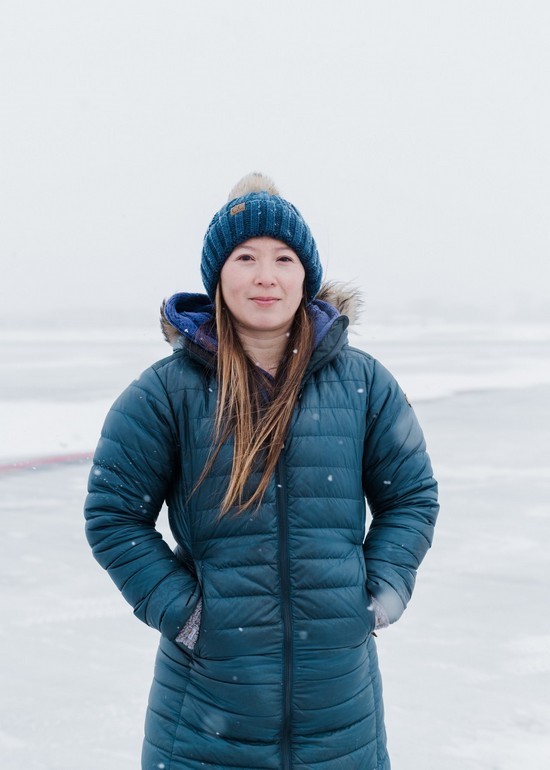

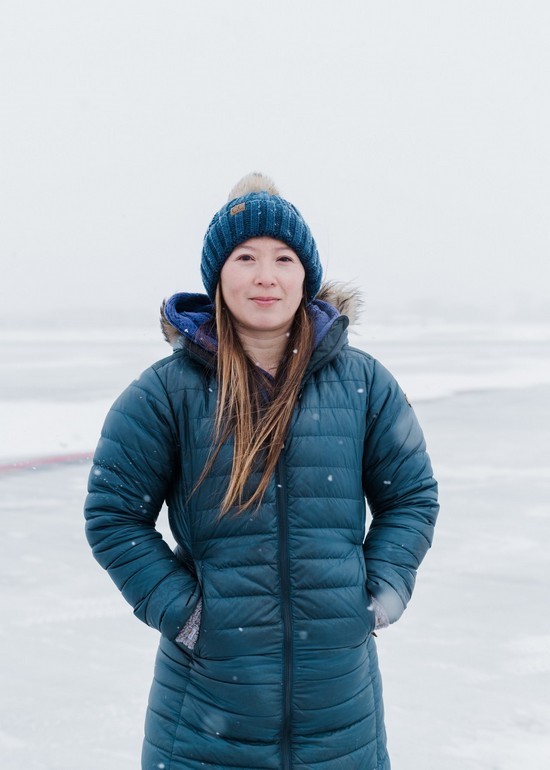

Lan Vu, a battery engineer at Beta, an aviation tech startup, at the company’s headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

“You’re looking at history,” Caputo said recently, speaking from the cockpit of a plane trailing the Alia at close distance. It had an exotic, almost whimsical shape, like an Alexander Calder sculpture, and it banked and climbed in near silence.

It is, essentially, a flying battery, which represents a long-held aviation goal: an aircraft with no need for jet fuel and therefore no carbon emissions, a plane that can take off and land without a runway and quietly hop from recharging station to recharging station, like a large drone.

The Alia was made by Beta Technologies, where Caputo is a flight instructor. A five-year-old startup that is unusual in many respects, the company is the brainchild of Martine Rothblatt, founder of Sirius XM and pharmaceutical company United Therapeutics, and Kyle Clark, a Harvard-trained engineer, and former professional hockey player. It has a unique mission, focused on cargo rather than passengers. And despite raising a formidable treasure chest in capital, it is based in Burlington, Vermont, population 45,000, more than 4,000km from Silicon Valley.

Workers at Beta, an aviation tech startup, prepare for testing of an Alia, the company’s electric vertical aircraft, in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

Despite the excitement about e-planes, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has never certified electric propulsion as safe for commercial use. Companies expect that to change in the coming years, but only gradually, as safety concerns are worked out. As that process occurs, new forms of aviation are likely to appear, planes never seen outside of testing grounds. Those planes will have limitations as to how far and fast they can fly, but they will do things other planes can’t, such as hover and take off from “runways in the sky”.

They will also — perhaps most important for an industry dependent on fossil fuels — cut down on commercial aviation’s enormous contribution to climate change, currently calculated as 3 percent to 4 percent of greenhouse gases globally.

“It’s gross,” Clark said. “If we don’t (cut down), the consequences are that we’ll destroy the planet.”

A grand vision

Clark flew alone for the first time in 1997 on a plane from Burlington to Erie, Pennsylvania. Clark, then 16, had just been selected by the USA Hockey national team. “I was the worst player on the ice,” he said, “so I decided to fight all the opposing players.” As a result, “the team named me captain.”

Kyle Clark, a founder of Beta, an aviation tech startup, in Burlington, Vermont, on February 21, 2022.

At 6-foot-7, a self-described physical “freak,” Clark would go on to a brief professional hockey career as an extremely low-scoring right-wing and enforcer. (His LinkedIn page shows him brawling, helmetless, as a member of the Washington Capitals organization.)

After a stint in Finland’s professional hockey league, he left the sport and received an undergraduate degree in materials science at Harvard, where he wrote a thesis on a plane piloted like a motorcycle and fueled by alternative energy. It was named the engineering department’s paper of the year.

He then found himself considering a career on Wall Street, doing something he didn’t want to do away from where he wanted to be: back in Vermont.

“There’s a brain drain” among engineers from his home state, he said. “People go away to college and come back when they’re 40, because they realize San Francisco or Boston isn’t the cat’s meow.” Returning to Burlington in his mid-20s, Clark became director of engineering at a company that designed power converters for Tesla.

Alia, the electric vertical aircraft built by Beta during testing at the company’s headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

In 2017, he attended a conference where Rothblatt made her pitch for an e-helicopter.

“There were like 30 people in the room, none of whom excited me,” Rothblatt recalled. “Then Kyle stood up and said, ‘I’m an electronics and power systems person, and I’m confident we can achieve your specification with a demonstration flight within one to two years.’ Other people were shaking their head. He was probably the youngest guy in the room. So I came up to him during break and said, ‘Where’s your company located?’ And he said, ‘I live in Vermont.’”

A few weeks later, after a second meeting, Clark drew a watercolor of his design and sent it to Rothblatt. Within hours, $1.5 million in seed capital for Beta Technologies had been wired to his bank account.

“He drew a nice design,” Rothblatt said.

A prototype with four tilting propellers was assembled in eight months, with Clark piloting the vehicle himself. Built in Burlington, the plane had to be flown over Lake Champlain, away from population centers.

“It was so fun to fly it that we found an excuse to every chance we could,” Clark told an audience at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2019. Ultimately, though, it turned out to have too complex a design and Clark threw it out.

He created a streamlined prototype modeled after the Arctic tern, a small, slow bird capable of flying uncanny distances without landing.

Since then, Beta’s workforce has grown to more than 350 from 30. The company’s headquarters have expanded to several buildings wrapping around the runway at Burlington International Airport, with plans for an additional 40-acre campus.

A plane such as Beta’s could be a catalyst for “decentralizing” the hub and spoke system, the company hopes, taking dependence on shipping centers such as Louisville, Kentucky, and Memphis, Tennessee, out of the equation and rebuilding the supply chain.

“If you think about a path between two cities where there’s no direct air service,” said Blain Newton, Beta’s chief finance and operations officer, “the only way is by taking one connection, two connections.” Alia can change that — especially by increasing access to less-populated parts of the country, such as northern Vermont.

‘The DNA of Vermont’

Beta’s headquarters at the Burlington Airport — close enough to be seen from the Terminal B waiting area — still has the youthful informality of a startup. On a December morning in the hangar, Naughty by Nature’s “Feel Me Flow” penetrated the din of whirring propellers and industrial tools. The heavily tattooed Clark, whose idea of formal wear seems to be rotating his baseball cap forward, pinballed around the hangar, grabbing stray machinery and vaulting up staircases with the agility of a professional athlete.

Before he joined Beta, Newton worked in health care. At his job interview, Clark took him for a helicopter ride.

“He gave me the controls and said, ‘Your aircraft. Figure it out,’” Newton recalled, chuckling. “I’d never flown before. I ended up taking a 65 percent pay cut to work for him.”

On their way back, with Clark back at the controls, the helicopter flew over Burlington, a city built largely around the University of Vermont and companies known for their progressive bona fides, including Seventh Generation and Ben & Jerry’s. The city also hosts a number of renewable energy startups.

“Clean energy is built into the DNA of Vermont,” said Russ Scully, a Burlington entrepreneur who raised capital for Beta. The state’s electricity supply is carbon free (thanks, in part, to higher use of nuclear power than any other state), and Burlington is closer to becoming net zero than almost any municipality in the country. In the Beta parking lot, many cars have charging cables inserted.

The futurist and the test pilot

Is the world ready for wingless hovercraft levitating over cities and hot-rodding through congested air corridors?

The consensus within the industry is that the FAA, which regulates half the world’s aviation activity, is several years from certifying urban air mobility.

“It’s a big burden of proof to bring new technology to the FAA — appropriately so,” Clark said. Currently, the certification process for a new plane or helicopter takes two to three years on average. For an entirely new type of vehicle, it could be considerably longer. (One conventionally powered aircraft that can take off and land without a runway had its first flight in 2003. It remains uncertified.)

Rothblatt has built a career out of the long view. She is a celebrated futurist who has argued passionately for transhumanism, or the belief that human beings will eventually merge with machines and upload consciousness to a digital realm. And she has taken positions on issues such as xenotransplantation — the interchange of organs between species, including humans — considered audacious not long ago, though no longer.

Yet, in certain ways, she and Clark make for unlikely partners. Clark has a familiar demeanor for a test pilot: exuberant, risk-taking, hyperconfident.

Nathan Diller, an Air Force colonel, is not a futurist, but his job is to find and support companies doing forward-thinking, futuristic things.

Military applications of a vehicle such as the Alia — especially logistics — have gotten attention at the highest levels of the Air Force, which has backed Beta and some peers through the accelerator Agility Prime.

Last month, for the first time, uniformed Air Force pilots flew an Alia, soaring above Lake Champlain in a plane powered only by a battery.

Diller sees this kind of transport as a national security issue, in part because of its potential to reduce fuel consumption, but what seems to intrigue him most is “the democratization of air travel.”

He grew up flying experimental planes on an organic farm in West Texas, aware of the limits on where a plane can land and who can fly. Looking at a floating sculpture twirling above a lake, he sees a different future for aviation: “Everyone a pilot, everywhere a runway.”

Read more Technology

Jordan News

In the mind of Christopher Caputo, a pilot, each moment signals a paradigm shift in aviation.

Lan Vu, a battery engineer at Beta, an aviation tech startup, at the company’s headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

“You’re looking at history,” Caputo said recently, speaking from the cockpit of a plane trailing the Alia at close distance. It had an exotic, almost whimsical shape, like an Alexander Calder sculpture, and it banked and climbed in near silence.

It is, essentially, a flying battery, which represents a long-held aviation goal: an aircraft with no need for jet fuel and therefore no carbon emissions, a plane that can take off and land without a runway and quietly hop from recharging station to recharging station, like a large drone.

The Alia was made by Beta Technologies, where Caputo is a flight instructor. A five-year-old startup that is unusual in many respects, the company is the brainchild of Martine Rothblatt, founder of Sirius XM and pharmaceutical company United Therapeutics, and Kyle Clark, a Harvard-trained engineer, and former professional hockey player. It has a unique mission, focused on cargo rather than passengers. And despite raising a formidable treasure chest in capital, it is based in Burlington, Vermont, population 45,000, more than 4,000km from Silicon Valley.

Workers at Beta, an aviation tech startup, prepare for testing of an Alia, the company’s electric vertical aircraft, in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

Despite the excitement about e-planes, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has never certified electric propulsion as safe for commercial use. Companies expect that to change in the coming years, but only gradually, as safety concerns are worked out. As that process occurs, new forms of aviation are likely to appear, planes never seen outside of testing grounds. Those planes will have limitations as to how far and fast they can fly, but they will do things other planes can’t, such as hover and take off from “runways in the sky”.

They will also — perhaps most important for an industry dependent on fossil fuels — cut down on commercial aviation’s enormous contribution to climate change, currently calculated as 3 percent to 4 percent of greenhouse gases globally.

“It’s gross,” Clark said. “If we don’t (cut down), the consequences are that we’ll destroy the planet.”

A grand vision

Clark flew alone for the first time in 1997 on a plane from Burlington to Erie, Pennsylvania. Clark, then 16, had just been selected by the USA Hockey national team. “I was the worst player on the ice,” he said, “so I decided to fight all the opposing players.” As a result, “the team named me captain.”

Kyle Clark, a founder of Beta, an aviation tech startup, in Burlington, Vermont, on February 21, 2022.

At 6-foot-7, a self-described physical “freak,” Clark would go on to a brief professional hockey career as an extremely low-scoring right-wing and enforcer. (His LinkedIn page shows him brawling, helmetless, as a member of the Washington Capitals organization.)

After a stint in Finland’s professional hockey league, he left the sport and received an undergraduate degree in materials science at Harvard, where he wrote a thesis on a plane piloted like a motorcycle and fueled by alternative energy. It was named the engineering department’s paper of the year.

He then found himself considering a career on Wall Street, doing something he didn’t want to do away from where he wanted to be: back in Vermont.

“There’s a brain drain” among engineers from his home state, he said. “People go away to college and come back when they’re 40, because they realize San Francisco or Boston isn’t the cat’s meow.” Returning to Burlington in his mid-20s, Clark became director of engineering at a company that designed power converters for Tesla.

Alia, the electric vertical aircraft built by Beta during testing at the company’s headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, on January 28, 2022.

In 2017, he attended a conference where Rothblatt made her pitch for an e-helicopter.

“There were like 30 people in the room, none of whom excited me,” Rothblatt recalled. “Then Kyle stood up and said, ‘I’m an electronics and power systems person, and I’m confident we can achieve your specification with a demonstration flight within one to two years.’ Other people were shaking their head. He was probably the youngest guy in the room. So I came up to him during break and said, ‘Where’s your company located?’ And he said, ‘I live in Vermont.’”

A few weeks later, after a second meeting, Clark drew a watercolor of his design and sent it to Rothblatt. Within hours, $1.5 million in seed capital for Beta Technologies had been wired to his bank account.

“He drew a nice design,” Rothblatt said.

A prototype with four tilting propellers was assembled in eight months, with Clark piloting the vehicle himself. Built in Burlington, the plane had to be flown over Lake Champlain, away from population centers.

“It was so fun to fly it that we found an excuse to every chance we could,” Clark told an audience at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2019. Ultimately, though, it turned out to have too complex a design and Clark threw it out.

He created a streamlined prototype modeled after the Arctic tern, a small, slow bird capable of flying uncanny distances without landing.

Since then, Beta’s workforce has grown to more than 350 from 30. The company’s headquarters have expanded to several buildings wrapping around the runway at Burlington International Airport, with plans for an additional 40-acre campus.

A plane such as Beta’s could be a catalyst for “decentralizing” the hub and spoke system, the company hopes, taking dependence on shipping centers such as Louisville, Kentucky, and Memphis, Tennessee, out of the equation and rebuilding the supply chain.

“If you think about a path between two cities where there’s no direct air service,” said Blain Newton, Beta’s chief finance and operations officer, “the only way is by taking one connection, two connections.” Alia can change that — especially by increasing access to less-populated parts of the country, such as northern Vermont.

‘The DNA of Vermont’

Beta’s headquarters at the Burlington Airport — close enough to be seen from the Terminal B waiting area — still has the youthful informality of a startup. On a December morning in the hangar, Naughty by Nature’s “Feel Me Flow” penetrated the din of whirring propellers and industrial tools. The heavily tattooed Clark, whose idea of formal wear seems to be rotating his baseball cap forward, pinballed around the hangar, grabbing stray machinery and vaulting up staircases with the agility of a professional athlete.

Before he joined Beta, Newton worked in health care. At his job interview, Clark took him for a helicopter ride.

“He gave me the controls and said, ‘Your aircraft. Figure it out,’” Newton recalled, chuckling. “I’d never flown before. I ended up taking a 65 percent pay cut to work for him.”

On their way back, with Clark back at the controls, the helicopter flew over Burlington, a city built largely around the University of Vermont and companies known for their progressive bona fides, including Seventh Generation and Ben & Jerry’s. The city also hosts a number of renewable energy startups.

“Clean energy is built into the DNA of Vermont,” said Russ Scully, a Burlington entrepreneur who raised capital for Beta. The state’s electricity supply is carbon free (thanks, in part, to higher use of nuclear power than any other state), and Burlington is closer to becoming net zero than almost any municipality in the country. In the Beta parking lot, many cars have charging cables inserted.

The futurist and the test pilot

Is the world ready for wingless hovercraft levitating over cities and hot-rodding through congested air corridors?

The consensus within the industry is that the FAA, which regulates half the world’s aviation activity, is several years from certifying urban air mobility.

“It’s a big burden of proof to bring new technology to the FAA — appropriately so,” Clark said. Currently, the certification process for a new plane or helicopter takes two to three years on average. For an entirely new type of vehicle, it could be considerably longer. (One conventionally powered aircraft that can take off and land without a runway had its first flight in 2003. It remains uncertified.)

Rothblatt has built a career out of the long view. She is a celebrated futurist who has argued passionately for transhumanism, or the belief that human beings will eventually merge with machines and upload consciousness to a digital realm. And she has taken positions on issues such as xenotransplantation — the interchange of organs between species, including humans — considered audacious not long ago, though no longer.

Yet, in certain ways, she and Clark make for unlikely partners. Clark has a familiar demeanor for a test pilot: exuberant, risk-taking, hyperconfident.

Nathan Diller, an Air Force colonel, is not a futurist, but his job is to find and support companies doing forward-thinking, futuristic things.

Military applications of a vehicle such as the Alia — especially logistics — have gotten attention at the highest levels of the Air Force, which has backed Beta and some peers through the accelerator Agility Prime.

Last month, for the first time, uniformed Air Force pilots flew an Alia, soaring above Lake Champlain in a plane powered only by a battery.

Diller sees this kind of transport as a national security issue, in part because of its potential to reduce fuel consumption, but what seems to intrigue him most is “the democratization of air travel.”

He grew up flying experimental planes on an organic farm in West Texas, aware of the limits on where a plane can land and who can fly. Looking at a floating sculpture twirling above a lake, he sees a different future for aviation: “Everyone a pilot, everywhere a runway.”

Read more Technology

Jordan News