Some microchips feature more than 50 billion tiny transistors that are 10,000

times smaller than the width of a human hair. They are made on gigantic,

ultraclean factory room floors that can be seven stories tall and run the

length of four football fields.

اضافة اعلان

Microchips are in many ways the lifeblood of the

modern economy. They power computers, smartphones, cars, appliances, and scores

of other electronics. But the world’s demand for them has surged since the

pandemic, which also caused supply-chain disruptions, resulting in a global

shortage.

Large ducts carry gases away from processing machines at the Intel chip-manufacturing plant in Hillsboro, Oregon, on September 22, 2021.

Large ducts carry gases away from processing machines at the Intel chip-manufacturing plant in Hillsboro, Oregon, on September 22, 2021.

That, in turn, is fueling inflation and raising

alarms that the

US is becoming too dependent on chips made abroad. The US

accounts for only about 12 percent of global semiconductor manufacturing

capacity; more than 90 percent of the most advanced chips come from Taiwan.

Intel, a

Silicon Valley titan that is seeking to

restore its longtime lead in chip manufacturing technology, is making a $20

billion bet that it can help ease the chip shortfall. It is building two

factories at its chip-making complex in Chandler, Arizona, that will take three

years to complete, and recently announced plans for a potentially bigger

expansion, with new sites in New Albany, Ohio, and Magdeburg, Germany.

Why does making millions of these tiny components

mean building — and spending — so big? A look inside Intel production plants in

Chandler and Hillsboro, Oregon, provides some answers.

What chips do

Chips, or integrated

circuits, began to replace bulky individual transistors in the late 1950s. Many

of those tiny components are produced on a piece of silicon and connected to

work together. The resulting chips store data, amplify radio signals and

perform other operations; Intel is famous for a variety called microprocessors,

which perform most of the calculating functions of a computer.

An Intel employee with a tray of Ponte Vecchio microchips before the heat spreader is attached at the company’s complex in Chandler, Arizona, on November 17, 2021.

An Intel employee with a tray of Ponte Vecchio microchips before the heat spreader is attached at the company’s complex in Chandler, Arizona, on November 17, 2021.

Intel has managed to shrink transistors on its

microprocessors to mind-bending sizes. But the rival

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. can make even tinier components, a key reason Apple chose it

to make the chips for its latest iPhones.

Such wins by a company based in Taiwan, an island

that

China claims as its own, add to signs of a growing technology gap that

could put advances in computing, consumer devices and military hardware at risk

from both China’s ambitions and natural threats in Taiwan such as earthquakes

and drought. And it has put a spotlight on Intel’s efforts to recapture the

technology lead.

How chips are made

Chipmakers are packing more and more transistors onto each piece of

silicon, which is why

technology does more each year. It’s also the reason that

new chip factories cost billions and fewer companies can afford to build them.

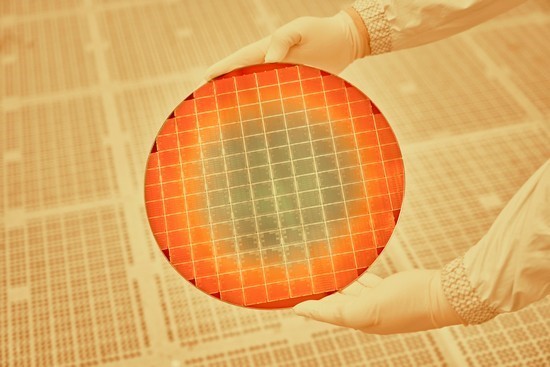

In addition to

paying for buildings and machinery, companies must spend heavily to develop the

complex processing steps used to fabricate chips from plate-size silicon wafers

— which is why the factories are called “fabs”.

Pods holding up to 25 of the silicon wafers used to make microchips move on automated overhead tracks at Intel’s complex in Chandler, Arizona, on November 17, 2021.

Pods holding up to 25 of the silicon wafers used to make microchips move on automated overhead tracks at Intel’s complex in Chandler, Arizona, on November 17, 2021.

Enormous machines

project designs for chips across each wafer, and then deposit and etch away layers

of materials to create their transistors and connect them. Up to 25 wafers at a

time move among those systems in special pods on automated overhead tracks.

Processing a wafer

takes thousands of steps and up to two months. TSMC has set the pace for output

in recent years, operating “gigafabs,” sites with four or more production

lines. Dan Hutcheson, vice chair of market-research firm TechInsights,

estimated that each site can process more than 100,000 wafers a month. He

estimated the capacity of Intel’s two planned $10 billion facilities in

Arizona at roughly 40,000 wafers a month each.

How chips are

packaged

After processing, the wafer is sliced into individual chips. These are

tested and wrapped in plastic packages to connect them to circuit boards or

parts of a system.

That step has

become a new battleground, because it is more difficult to make transistors

even smaller. Companies are now stacking multiple chips or laying them side by

side in a package, connecting them to act as a single piece of silicon.

Where packaging a

handful of chips together is now routine, Intel has developed one advanced

product that uses new technology to bundle a remarkable 47 individual chips,

including some made by TSMC and other companies as well those produced in Intel

fabs.

What makes chip

factories different

Intel chips typically sell for hundreds to thousands of dollars each.

Intel in March released its fastest microprocessor for desktop computers, for

example, at a starting price of $739. A piece of dust invisible to the human

eye can ruin one. So fabs have to be cleaner than a hospital operating room and

need complex systems to filter air and regulate temperature and humidity.

Fabs must also be

impervious to just about any vibration, which can cause costly equipment to

malfunction. So fab clean rooms are built on enormous concrete slabs on special

shock absorbers.

Also critical is

the ability to move vast amounts of liquids and gases. The top level of Intel’s

factories, which are about 22 meters tall, have giant fans to help circulate

air to the clean room directly below. Below the clean room are thousands of

pumps, transformers, power cabinets, utility pipes and chillers that connect to

production machines.

The need for water

Fabs are water-intensive

operations. That’s because water is needed to clean wafers at many stages of

the production process.

Intel’s two sites in Chandler collectively draw

about 11 million gallons of water a day from the local utility. Intel’s future

expansion will require considerably more, a seeming challenge for a

drought-plagued state like Arizona, which has cut water allocations to farmers.

But farming actually consumes much more water than a chip plant.

Intel says its Chandler sites, which rely on

supplies from three rivers and a system of wells, reclaim about 82 percent of

the freshwater they use through filtration systems, settling ponds and other

equipment. That water is sent back to the city, which operates treatment

facilities that Intel funded, and which redistributes it for irrigation and

other nonpotable uses.

The water treatment plant at the Intel chip-manufacturing plant in Hillsboro, Oregon, on September 22, 2021.

The water treatment plant at the Intel chip-manufacturing plant in Hillsboro, Oregon, on September 22, 2021.

Intel hopes to help boost the water supply in

Arizona and other states by 2030, by working with environmental groups and

others on projects that save and restore water for local communities.

How fabs are built

To build its future

factories, Intel will need roughly 5,000 skilled construction workers for three

years.

They have a lot to do. Excavating the foundations is

expected to remove 890,000 cubic yards of dirt, carted away at a rate of one

dump truck per minute, said Dan Doron, Intel’s construction chief.

The company expects to pour more than about 340,227

cubic meters of concrete and use 100,000 tonnes of reinforcement steel for the

foundations — more than in constructing the world’s tallest building, the in Dubai, the UAE.

Some cranes for

the construction are so large that more than 100 trucks are needed to bring the

pieces to assemble them, Doron said. The cranes will lift, among other things,

55-tonne chillers for the new fabs.

Patrick Gelsinger, who became Intel’s CEO a year ago, is lobbying Congress to provide

grants for fab construction and tax credits for equipment investment. To manage

Intel’s spending risk, he plans to emphasize construction of fab “shells” that

can be outfitted with equipment to respond to market changes.

To address the chip shortage, Gelsinger will have to make

good on his plan to produce chips designed by other companies. But a single

company can do only so much; products like phones and cars require components

from many suppliers, as well as older chips. And no country can stand alone in

semiconductors, either. Though boosting domestic manufacturing can reduce

supply risks somewhat, the chip industry will continue to rely on a complex

global web of companies for raw materials, production equipment, design

software, talent, and specialized manufacturing.

Read more Technology

Jordan News