Chris

Chapman used to own one of the most valuable commodities in the crypto world: a

unique digital image of a spiky-haired ape dressed in a spacesuit.

اضافة اعلان

Chapman bought

the

non-fungible token (NFT) last year, as a widely hyped series of digital

collectibles called the Bored Ape Yacht Club became a phenomenon. In December,

he listed his Bored Ape for sale on OpenSea, the largest NFT marketplace,

setting the price at about $1 million. Two months later, as he got ready to

take his daughters to the zoo, OpenSea sent him a notification: The ape had

been sold for roughly $300,000.

A crypto scammer exploited a flaw in

OpenSea’s

system to buy the ape for significantly less than its worth, said Chapman, who

runs a construction business in Texas. Last month, OpenSea offered him about

$30,000 in compensation, he said, which he turned down in hopes of negotiating

a larger payout.

The company has

made “a lot of stupid, dumb mistakes,” Chapman, 35, said. “They don’t really

know what they’re doing.”

Chapman is one

of many crypto enthusiasts who have raised questions about OpenSea, an

eBay-like site where people can browse millions of NFTs, buy the images and put

their own up for sale. In the last 18 months, OpenSea has become the dominant

NFT marketplace and one of the highest-profile crypto startups. The company has

raised more than $400 million from investors, valuing it at a staggering $13.3

billion, and recruited executives from tech giants like Meta and Lyft.

But as OpenSea

has grown, it has struggled to prevent theft and fraud. The glitch that cost

Chapman his ape has led to months of recriminations, forcing the startup to

make more than $6 million in payouts to NFT traders.

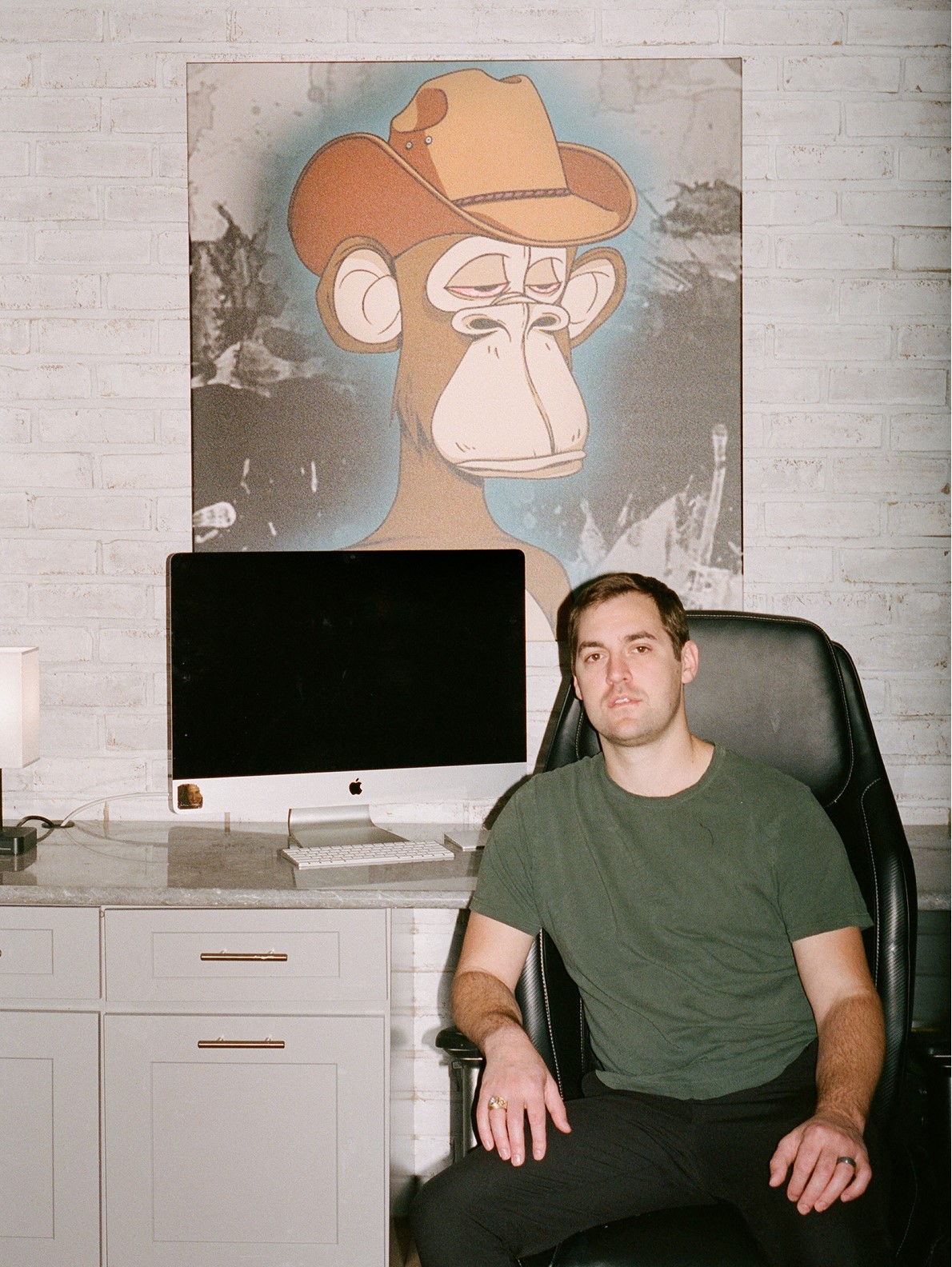

Chris Chapman at his home studio in Houston, April 9, 2022. OpenSea, one of the highest-profile crypto start-ups, is facing a backlash over stolen and plagiarized nonfungible tokens, or NFTs.

Chris Chapman at his home studio in Houston, April 9, 2022. OpenSea, one of the highest-profile crypto start-ups, is facing a backlash over stolen and plagiarized nonfungible tokens, or NFTs.

Customers also

complain that OpenSea is slow to block the sale of NFTs that were seized by

hackers, who can turn a quick profit by flipping the stolen goods. And

plagiarized art has proliferated on the site, outraging artists who once viewed

NFTs as a financial lifeline. The company is facing at least four lawsuits from

traders, and one of its former executives was indicted this month on charges

related to insider trading involving NFTs.

OpenSea’s troubles are piling up just as demand for

NFTs cools amid a crash in cryptocurrency prices. NFT sales have dropped about

90% since September, according to the industry data tracker NonFungible.

OpenSea is also contending with competition from newer marketplaces built by

established crypto companies like Coinbase.

The company’s

clashes with users illustrate some of the central tensions of web3, a utopian

vision of a more democratic internet controlled by regular people rather than

giant tech companies. Like many

crypto platforms, OpenSea does not collect the

names of most of its customers and advertises itself as a “self-serve” gateway

to a loosely regulated market. But users increasingly want the company to act

more like a traditional business by compensating fraud victims and cracking

down on theft.

In three interviews,

OpenSea executives acknowledged the scale of the problems and said the company

was taking steps to improve trust and safety. OpenSea, which is based in New

York, has hired more customer-service staff, with the aim of responding to all

complaints within 24 hours. The company freezes listings of stolen NFTs and has

a new screening process to prevent plagiarized content from circulating on the

platform.

“Like every tech

company, there’s a period where you’re catching up,” said Devin Finzer, 31, OpenSea’s

CEO. “You’re trying to do everything you can to accommodate the brand-new users

that are coming into the space.”

OpenSea was

founded 4 1/2 years ago by Finzer, a Brown University graduate whose previous

startup, a personal-finance app, was sold to the financial technology company

Credit Karma, and Alex Atallah, a former engineer at the software firm

Palantir. They are now among the world’s richest crypto billionaires, according

to Forbes.

Their business

model is simple. OpenSea takes a 2.5 percent cut each time an NFT is sold on

its platform. Last year, business spiked as NFTs became a cultural sensation

and the value of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies skyrocketed.

Because OpenSea collects a fee from each NFT sale,

some users argue that the company has a financial incentive not to clamp down

on the sale of stolen goods. This year, Robert Armijo, an investor in Nevada,

sued OpenSea for failing to stop a hacker who had stolen several of his NFTs

from selling one of them on the platform. (OpenSea’s lawyers called the

complaint “a nonstarter” and said the company acted promptly to stop the other

stolen NFTs from being sold.)

In February, Eli Shapira, a former tech executive,

clicked on a link that he said gave a hacker access to the digital wallet where

he stores his NFTs. The thief sold two of Shapira’s most valuable NFTs on

OpenSea for a total of more than $100,000.

Within hours,

Shapira contacted OpenSea to report the hack. But the company never took

action, he said. Since then, he has used public data to track the account that

seized his NFTs and has seen the hacker sell other images on OpenSea, possibly

from more thefts.

“It’s very easy

for these hackers to go and open an account there and immediately trade or sell

whatever they’ve stolen,” Shapira said. “All of these guys need to step up

security.”

Last month,

after The New York Times asked OpenSea about the case, the company responded to

Shapira and froze any future sales of the stolen NFTs.

Anne

Fauvre-Willis, who oversees OpenSea’s customer-support efforts, said the

company had been working to improve response times when users reported thefts.

“Getting faster is

important,” she said. “That’s something that we are investing in today and will

continue to make a huge investment on going forward.”

Read more Technology

Jordan News