From the culturally rich and historic streets

of

Jabal Amman to the modern mega malls of Abdali and Abdoun, Amman is a

wonderfully diverse and cosmopolitan city, and it is indisputably the heart of

our country.

اضافة اعلان

That being said, both public and private

institutions have put too much emphasis on this fact, which practically forces

Jordanians from smaller provincial towns to migrate to Amman for a greater

sense of opportunity.

The population of the city and its metropolis

has increased from almost 900,000 in 1979, to 1.864 million in 1999, and today

it sits at over four million.

Amman has grown more quickly than it can manage,

with a whopping rate of almost 2,400 per sq.km.

The city could not make the

necessary adjustments in time to accommodate a large mix of economic migrants

and refugees from war-torn neighboring countries, resulting in an

overwhelmingly congested city.

Residents of Amman will testify that the roads

barely fit the indescribable amount of cars that pass through them.

Yara

Shahzadeh, an Amman-born interpreter who has lived there for the majority of

her life has told me that it is very difficult to drive in the city and this

has translated to the city’s actual living spaces as well.

“Villas and homes used to be common, you would

never see apartment buildings before.

But I guess this happens with urban

expansion,” Shahzadeh said. Areas to walk and bike in are scarce, and making

the necessary space for more public transport is quite the challenge (although

the “Fast Bus” is a slight improvement in this regard).

In this article, I

wanted to look at the reasons for Amman’s

overcrowding and how those problems

could possibly be fixed.

For one, Jordan’s private sector is almost

completely based in Amman. In a list of Jordan’s 26 most prominent companies,

only four were based outside of Amman, an extremely disproportionate statistic

given that 42 percent of Jordan’s population lives in and around the capital.

The newest one of these companies was founded

in 1985, indicating that the exclusive focus on Amman has substantially

increased in the last few decades.

Understandably, it would be difficult for

private companies to set themselves up in smaller cities, but many larger

municipalities in Jordan do not experience much private sector growth.

For example, Irbid has almost 1 million people

living there, yet none of the 26 companies are based there.

This fact spurs

Jordanians who want to “make it big” to move to the capital. The underlying

reason for this is the disparity of funding between Amman and other cities in

Jordan.

In 2016, the World Bank found that JD430 million were allocated to the Greater

Amman Municipality. The following year, the municipal government of Zarqa, the

third largest city in Jordan, received a mere JD28 million in funding, despite

the fact that 635,160 people were there as of the last census.

Thus, the

government must find a way to allocate and bring revenue into other parts of

Jordan, lest its capital becomes too packed and unlivable.

Investing outside the capital

Although Jordan is a resource-poor nation,

various solutions can spread opportunity, and in turn, people, into other

governorates.

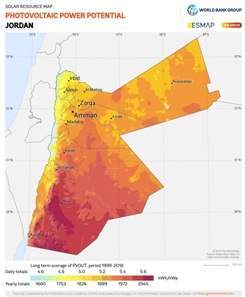

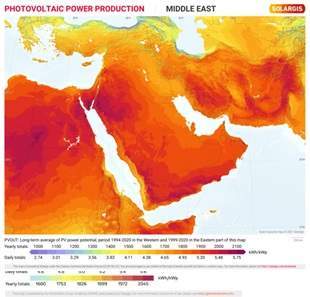

Maan, often overlooked as a small and isolated desert town, could

be converted into a bustling metropolis if its governorate’s solar power was

utilized.

Maan Governorate has a rate of solar capability that is almost

unmatched by any other part of the country, as it is located in an area with

near constant sunlight.

Even though Maan has the capability to provide

solar energy for the entire region, it only provides around 5 percent of

Jordan’s electrical energy.

If the government engages in the mass construction

of solar plants there, many workers might be attracted to help build the

project, with planners, administrators, and engineers moving in to supervise.

Such an endeavor could bring human and intellectual

capital to the second lowest developed region in Jordan.

The

job growth there will mean it would no longer be necessary for Maanis seeking

opportunities to go to Amman, and it could also attract people out of Amman,

allowing for a more spacious city.

The northern governorates of Jordan, namely

Irbid, Ajloun, Jerash, and Balqa are known nationwide for their spectacular and

green scenery, but little has been done to promote this specific aspect of that

region on a global scale.

Should Jordan’s tourism board promote the beautiful

mountains of the north to private companies, they could build resorts and

infrastructure geared towards tourists, in turn providing job opportunities,

financial growth, and a reason for residents in the area’s smaller towns to

stay.

This is similar to the mountain retreats that

exist in much of Europe or closer to home in Trabzon, Turkey, now an extremely

popular destination.

The same phenomenon of reverse migration that is possible

in Maan could occur there as more expansion requires more people.

A subway wouldn’t fix Amman

To reduce the amount of congestion in Amman,

it is necessary to come up with an efficient method of public transportation.

Although the new “Fast Bus” is a start, it doesn’t make a terribly large amount

of change.

For one, although there would be less vehicles on the road, there

still would be vehicles on the road, and for Amman’s roads to clear up, a

substantially large amount of people need to take a non-vehicular means of

transport.

One might think a metro or subway system would

solve this issue at first, but this seems unlikely to work in Amman’s case.

That is due to the fact that a city needs to be built around a subway system,

rather than the other way around.

For instance, New York City possesses one of

the longest subway systems in the world, built in 1904.

The very concept of a

subway is synonymous with the city and a whopping 42 percent of all residents

use the train as their main method of commuting.

Because of how long ago it was

built, much of New York City was built with the subway in mind, making it an

effective and convenient way of getting where one needs to be.

On the other hand, Cairo, another congested

Middle Eastern capital, built a metro system in 1988 and while it is fairly

expansive, most of the city was built before the metro was, meaning it is not

as advantageous as New York’s system.

This is probably why only 2 percent of those

living in Cairo actually use the metro as their main means of transportation.

Amman is already quite large, so a metro

system would not really do much to clear up the city’s roads.

Instead, an

interesting solution that has been implemented in much of Latin America might do

the trick.

Medellin, Colombia, had the idea of making a metro cable its main means of

transport. With stops around the city, it is cost-efficient,

climate-friendly, and has significantly reduced congestion.

It has also made distant suburbs of the city

more accessible and prosperous. This could have the effect of spreading people

and opportunities away from the city center.

The system has become popular that

it has been implemented in other Latin American cities, like Santo Domingo in

the Dominican Republic. Should Amman follow this example, the city and its

people might benefit immensely.

In conclusion, in order to make Amman a city

where people can once again move freely, solutions must be implemented within

the city, as well as in other parts of Jordan in order to stem rapid growth.

Should these suggestions be followed, not only might Amman be a much more comfortable

place to live in, but the other, often neglected areas of Jordan could see a

large amount of growth and prosperity come their way.

Read more

Opinion and Analysis