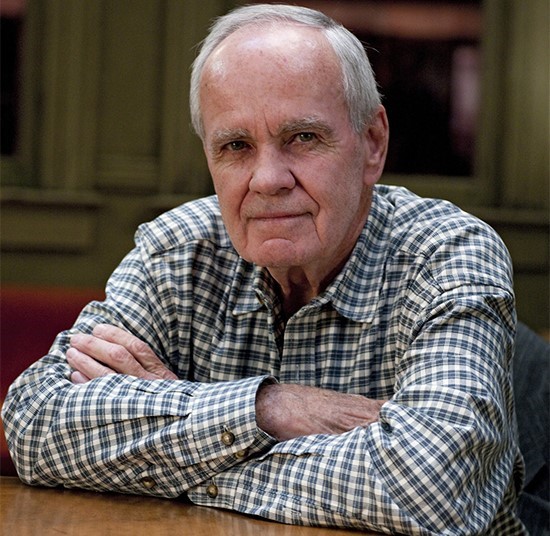

Artists

tend to simplify their form with age, and the big novel has traditionally been,

to paraphrase writers dead and living, no country for very old men. But this

fall, Cormac McCarthy, who is pushing 90, has arrived with a pair of audacious

linked novels: one a total banger and the other no embarrassment. If this is

what it sounds like to be on your last legs, young writers should ask their

server for whatever he is having. If McCarthy’s voice is any indication, he is

still limber enough to outrun an aggrieved cheetah in his drawers and stocking

feet.

اضافة اعلان

The first novel,

“

The Passenger”, was published in October. It blends the rowdy humor of some of

McCarthy’s early novels — especially “Suttree” (1979) — with the parched tone

of his more apocalyptic later work. It is the first novel I have read in years

that I feel I need to read three more times to fully understand and that I want

to read three more times simply to savor. It is so packed with funny, strange,

haunted sentences that other writers will be stealing lines from it for

epigraphs, as if it were Ecclesiastes, for the next 150 years.

The second of

these novels, “Stella Maris”, is out now. The title refers not to a stern-minded

young woman on horseback, which is what you might imagine if all you knew of

McCarthy was his Border Trilogy, but to a psychiatric hospital in Black River

Falls, Wisconsin.

It is where

20-year-old Alicia Western, a doctoral candidate in mathematics at the

University of Chicago, has checked herself in because she has been

hallucinating. Central among her visions is a shambolic dwarf with flippers and

a bent sense of humor known as the Thalidomide Kid. Alicia is also carrying a

plastic bag stuffed with $40,000, which she tries to give away to the

receptionist.

Novels are not

made, generally, to be filled entirely by talk. But that is what “Stella Maris”

is — transcriptions of therapy sessions with one of the hospital’s shrinks.

This is a Tom Stoppardesque bull session. Does it work? Uh-huh. Does it work

more fully if you have already read “The Passenger”? Absolutely.

Among the first

things we learn in Alicia’s sessions is that she is grieving the apparent death

of her brother, Bobby, who has been in a long coma since a car-racing accident

in Italy. Alicia and Bobby share a cursed inheritance; their father was a

physicist on the Manhattan Project. They are a high-voltage combination. They

share a genius for math — there are extra wires in their brains — and are so

close that incest is a simmering sub-theme in both novels.

If “Stella Maris”

is Alicia’s novel, “The Passenger” is Bobby’s. The earlier book is hard to

describe in a few sentences, but here goes. Bobby is a laconic salvage diver

who saw things he should not have. Before long, he is pursued not only by G-men

but, it seems, all the ghosts of the 20th century. He is an oddly upper-class

desperado, like

Townes Van Zandt. The whole thing reads like a cosmic, bleakly

funny John D. MacDonald thriller.

“The Passenger” is

a great New Orleans novel. It is a great food novel. (One important scene takes

place over a platter of the chicken a la grande at Mosca’s.) For anyone who

cares, it is also a great Knoxville, Tennessee, novel — Knoxville being where

McCarthy spent most of his childhood. It is filled with references to his

earlier work. It is a sprawling book of ideas — about mathematics, the nature

of knowledge, the importance of fast cars — that also contains flatulence

jokes. It slips into pretentiousness only to slip right back out again.

McCarthy knows that we know that he knows that he can lay it on thick.

“Stella Maris” is,

by comparison, a small and frequently elegiac novel. It is best read while you

are still buzzing from the previous book. Its themes are dark ones, and yet it

brings you home, like the piano coda at the end of “Layla”.

A lot of what

Alicia wants to talk about is mathematics; numbers filled her up, only to scour

her out. She has largely abandoned the practice. She pushed equations until

they led into chasms instead of bridges; they bent into witchcraft. McCarthy’s

own late-life interest in physics is everywhere apparent. Here is Alicia:

”Verbal

intelligence will only take you so far. There is a wall there, and if you don’t

understand numbers you won’t even see the wall. People from the other side will

seem odd to you. And you will never understand the latitude which they extend

to you. They will be cordial — or not — depending on their nature.”

No one in the real

world talks the way Alicia does — she is seeing with her third eye, flexing her

middle finger at the world, rocking her family’s thundersome legacy — but they

might if they could.

McCarthy being

McCarthy, Alicia has done the hard thinking about suicide. One of this book’s

bravura passages is her extended analysis of how miserable it would be to try

to kill yourself by drowning. The most moving moments in “Stella Maris” braid

her feelings for her brother, which go through her like a spear, with a sense

of intellectual futility.

Reading “Stella

Maris” after “The Passenger” is like trying to hang onto a dream. It is an

uncanny, unsettling dream, tuned into the static of the universe. In “The Road”

(2006), McCarthy put it this way: “Nobody wants to be here, and nobody wants to

leave.”

Read more Books

Jordan News