Reading Charlotte Van den Broeck’s beguiling book about architects and

melancholy on a blue and gold September day, I found it impossible not to think

of the twin towers.

اضافة اعلان

Widely

disfavored in their heyday by critics who preferred the elegant art deco

Empire State Building, the audacious modernist buildings — often compared to

exclamation points or front teeth and almost synonymous with Frank Sinatra

singing “New York, New York” — are now missed most terribly from the anodyne

skyline of downtown Manhattan.

Their

architect, Minoru Yamasaki, died of cancer long before 9/11, but he had

castigated himself during his lifetime for the failure and eventual demolition

of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex he had designed in St. Louis.

Though

she does not mention Yamasaki or either of his ill-fated projects, Van den

Broeck, a young Belgian poet, found herself preoccupied by the creators of

ambitious, imperfect structures — to the point where a boyfriend, Walter,

despite being a scholar himself, angrily calls her “compulsive” for sneaking

her research into plans for a Scottish vacation.

Pondering

“what makes a mistake larger than life, so all-encompassing that your life

itself becomes a failure,” she had set out to research a baker’s dozen of

“tragic architects” in America and Europe. They range from Francesco Borromini

of Rome, who lived in the more conventional Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s shadow

during the 17th century and eventually impaled himself on a saber; to Starr

Gideon Kempf, who made a kinetic sculpture garden in Colorado Springs,

Colorado, before putting a gun to his head in 1995.

“Architecture

has a more definite impact on the world” than language, is how Van den Broeck

explains her undertaking to one of many bemused sources. “Besides, buildings

have at least a shot at eternity. I don’t have any illusions about my poems.”

But

writing and architecture have plenty more in common: the possibility of

transcendent aesthetic experience; the process of making something from

nothing. “Bit by bit, putting it together,” as Stephen Sondheim wrote.

More

darkly, suicide has clouded both disciplines. Some building designers, Van den

Broeck discovers, ended their own lives after poor critical reception or

mechanical failure led to disrepute.

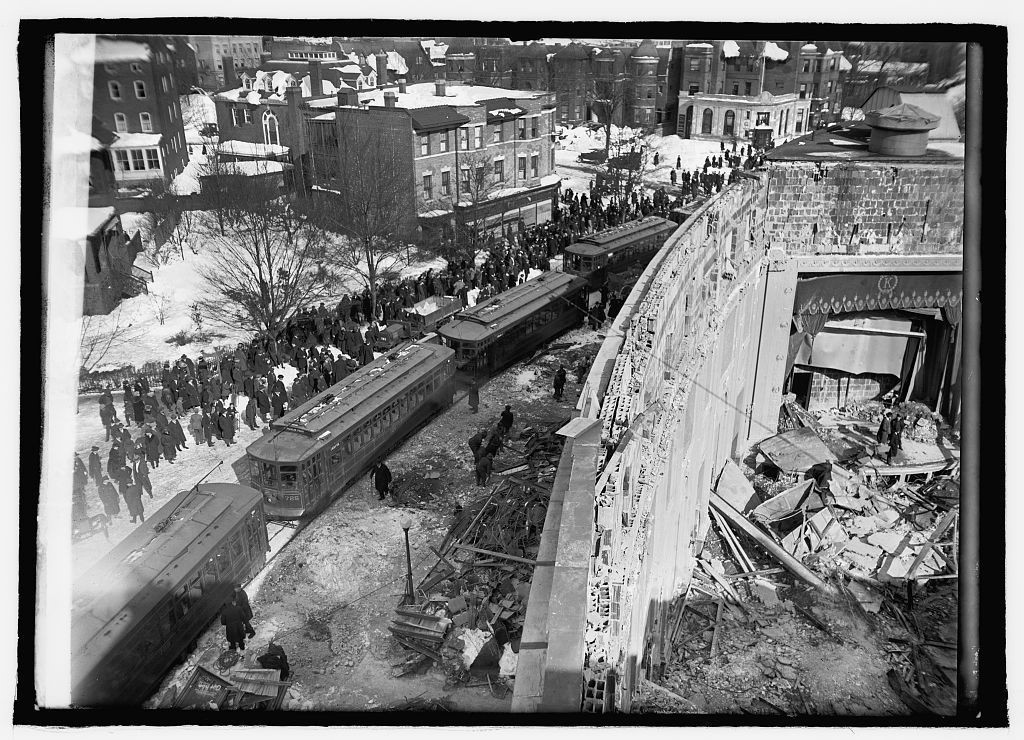

The ruins of Crandall’s Knickerbocker Theater in Washington, which collapsed in 1922. (File photo: NYTimes)

The ruins of Crandall’s Knickerbocker Theater in Washington, which collapsed in 1922. (File photo: NYTimes)

Her

chapter on Reginald Geare, who gassed himself five years after Crandall’s

Knickerbocker Theater in

Washington, DC, collapsed in 1922 under the weight of

a snowstorm, causing 95 fatalities, is particularly affecting. Harry Crandall,

the businessman who commissioned the building, would succumb in the same

manner. (“I’m despondent,” he wrote in his goodbye note, “and miss my theaters,

oh so much”.)

Other

architects Van den Broeck studies are oddly only rumored to have died by their

own hands, as if history’s collective consciousness is exacting revenge for

public works that didn’t work out.

“His

alleged suicide would at least lift him out of his colorless slot in history,”

she writes of military engineer Karl Pilhal in a letter to the exasperated

Walter. Pilhal supposedly could never get over the shame of not installing

proper toilets in his Rossauer Barracks, a dull medieval fortress along the

Danube originally constructed for Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria.

I

have no idea where this book, translated gracefully from the Dutch by David McKay,

will land in the Dewey Decimal System. The suicidal-architect conceit turns out

to be something of a facade for a blend of memoir, travelogue, and

philosophical tract. Moreover, Van den Broeck, using third-person omniscient

narration for many of her dead subjects and reconstructing dialogue without

documentation, freely admits she’s an unreliable narrator with a “proclivity

for twisting the truth”.

In

our moment of “quiet quitting”, resistance to corporate domination and a

conviction that capitalism is in decay, Bold Ventures does arrive as a timely

interrogation of what, exactly, constitutes success — of how to live.

Significant

chunks of the book explore Van den Broeck’s own writer’s block and insecurity.

“Mediocrity, crueler than mere failure,” she writes, echoing Antonio Salieri in

“Amadeus” in a chapter on the Vienna State Opera House, one of whose architects

hanged himself from a hat rack. “The remoteness of the masterpiece and the

peril of mediocrity make it impossible, most days, to put anything down on

paper.”

Underslept, underpaid, and

bogged down by a mysterious heaviness — one may wonder after reading Bold

Ventures if Van den Broeck is OK. And yet her tiered confection is a small

marvel: a monument to human beings continuing to reach for the skies, even

after their plans dissolve in dust.

Read more Books

Jordan News