Sitting at the bar in the exclusive Delta Club at Citi Field, where his beloved

New York Mets were in the process of sweeping the New York Yankees in the

Subway Series, the political fixer and venture capitalist Bradley Tusk

described his designs on the future.

اضافة اعلان

He talked up his $10 million philanthropic campaign

to build a system that would allow all Americans to vote on their phones; so

far, the campaign has funded pilot programs in seven states. He enthused over

an investment proposal from a Native American tribe to transform its South

Carolina reservation into the “Delaware of web3”. He pointed out a massive blue

billboard in the outfield advertising the blockchain firm Tezos, one of many

financial technology companies he advises.

But his latest project is set firmly in the present

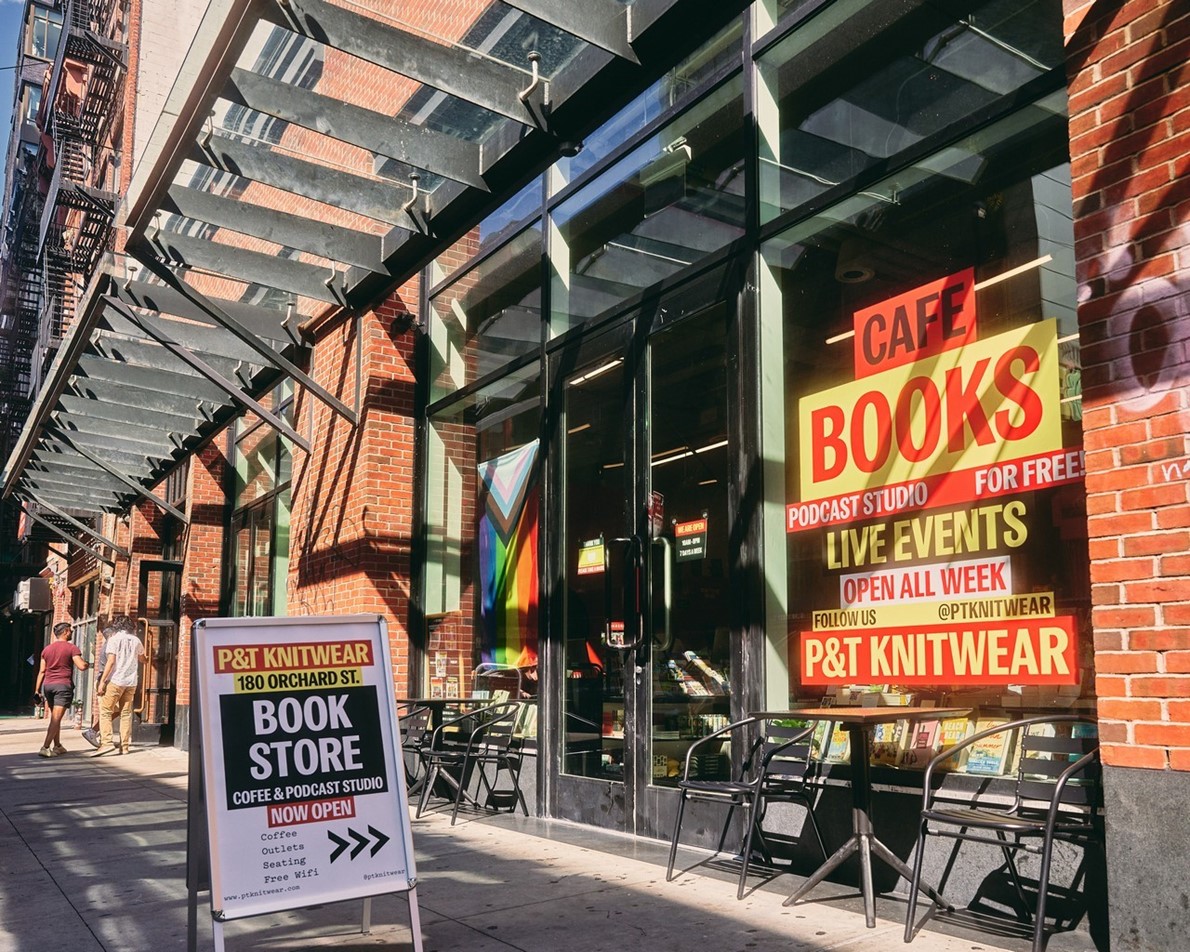

and relies on very old technology. Tusk, 48, has opened a brick-and-mortar

bookstore — one that he is marketing as family-owned and independent, a shift

away from his longstanding identity as one of New York City’s premier corporate

fixers.

The 278sq.m. space offers 10,000 books and a cafe,

as well as a podcast studio and an 80-seat amphitheater for readings and book

releases. Upcoming readings feature the kind of writers you would see on any

indie bookstore’s events calendar, like debut novelist Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

and poet Topaz Winters. At one recent talk, novelists Kevin Nguyen and YZ Chin

answered uncanny questions from the GPT-3 artificial intelligence program (“Who

are your influences?”) projected on a screen above their heads, to the

amusement of a youngish crowd with an array of literary tote bags.

But the store also recently hosted a book party to

celebrate a new memoir by Lis Smith, the political strategist who managed Pete

Buttigieg’s presidential campaign and who dated former Gov. Eliot Spitzer of

New York in his post-scandal years. The crowd included CNN host Brian Stelter;

political and corporate publicists Risa Heller and Stu Loeser; and Matthew

Hiltzik, another communications fixer whose clients have included the likes of

Hillary Rodham Clinton, Glenn Beck, and Johnny Depp.

The political crowd was a more familiar one than the

literary crowd for Tusk, who spent his formative years clawing his way up the

pecking order of Democratic politics. Along the way, he developed high-level

government connections and a nuanced feel for the levers of urban power, which

served him well when he transitioned to working as a consultant and lobbyist

for private companies battling regulators.

In college, Tusk interned for Mayor Ed Rendell of

Philadelphia and went on to work for Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York. He also

served as the deputy governor for Gov. Rod Blagojevich of Illinois, who was

later disgraced, until 2006. After a stint at Lehman Bros., shortly before it

imploded, he was tapped to run Michael Bloomberg’s campaign for a third term

for New York City mayor in 2009. He became an influential adviser to Bloomberg

after his victory; the mayor, in turn, became a mentor to Tusk. In 2010, soon

after the campaign, he started his own public relations and lobbying firm, Tusk

Strategies. “We’re expensive. We’re intense,” its website reads.

The Bloomberg administration was synonymous with

“corporate power”, said Michael Krasner, a former professor of political

science at Queens College and the co-director of the Taft Institute for

Government and Civic Education. The mayor’s pro-development policies, including

tax breaks for large businesses, profoundly changed the character of the city.

Critics have long accused the Bloomberg administration — which presided over

120 rezonings and the construction of more than 40,000 buildings — of ushering

in an era of extreme inequality, when huge glass towers went up and New York

transformed into a soulless “Potemkin village of what the city used to be”, as

historian Jeremiah Moss argues in his book “Vanishing New York”. Between 2000

and 2010, the number of bookstores in Manhattan reportedly declined from 204 to

135.

The bookstore, which opened in May, is the

culmination of what Tusk describes as a lifelong love affair with the written

word. Books offered Tusk “sanctuary,” he said, from bullies during his

middle-class upbringing on Long Island and in Sheepshead Bay in New York. He

majored in creative writing at the University of Pennsylvania before pursuing

politics.

“My thought was, I was a good enough writer to make

a living writing sitcoms, that was kind of my talent,” he said. (Tusk has never

written for a sitcom.) “I’m never going to win a National Book Award. I would

never win the Nobel Prize. I would never write a bestseller.”

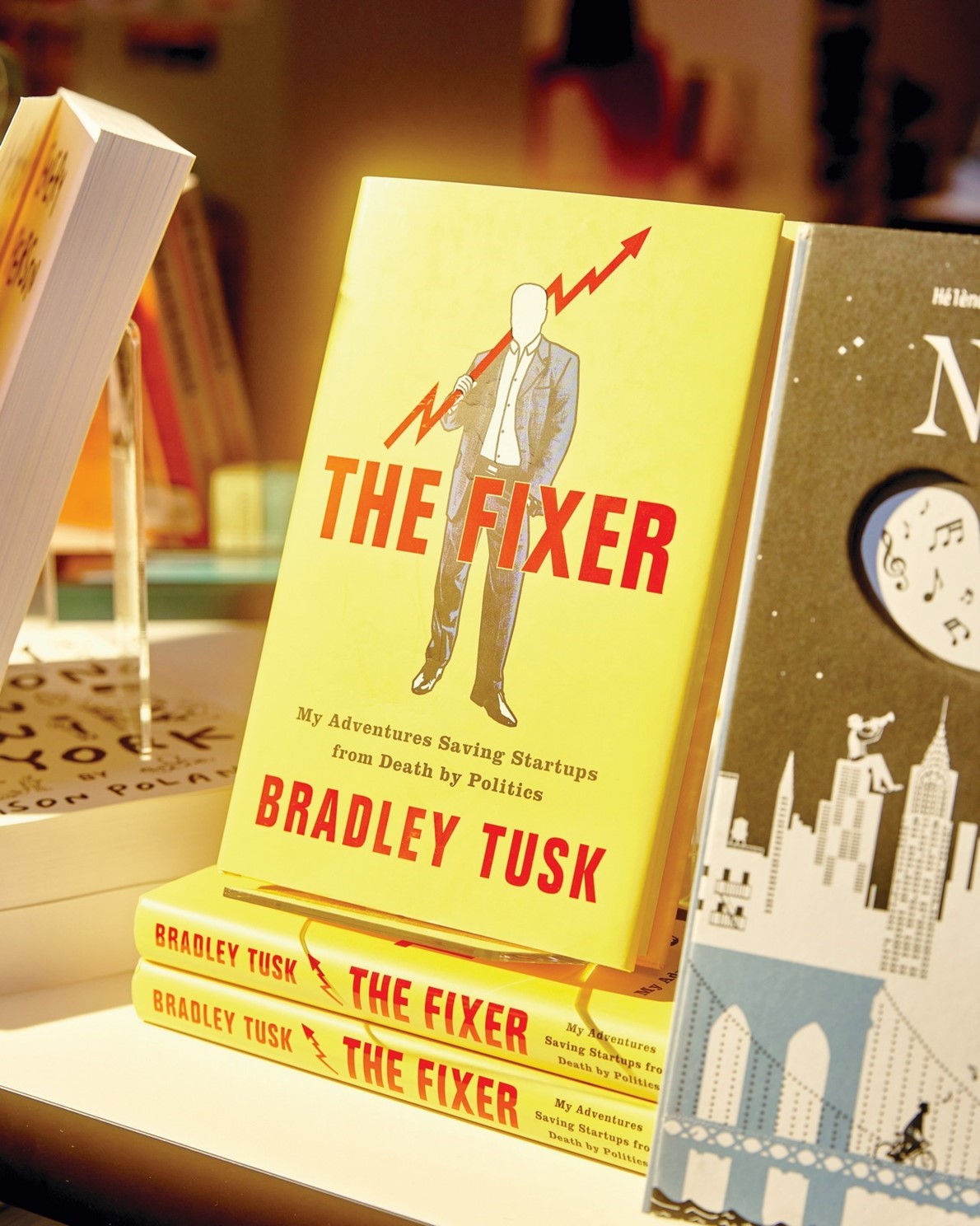

Over the last decade, he has returned to writing,

penning regular columns in business publications like Inc. and Fast Company. He

also published a memoir in 2018 titled “The Fixer: My Adventures Saving

Startups From Death by Politics.” It has sold 3,921 copies, according to

Nielsen BookScan, though that number might soon tick up: On a recent visit to

the shop, the book was prominently featured in the New York City section, its

bright yellow cover facing outward.

The title of the book is a reference to Tusk’s time

working for Uber founder Travis Kalanick, who hired Tusk for counsel in 2010 as

his startup battled local governments and taxi companies, including in New

York. Tusk lobbied on Uber’s behalf for the next five years and helped the company

steamroll regulation efforts by Mayor Bill de Blasio and the City Council,

enlisting drivers and riders to pressure the city. At one point, the Uber app

even added a mocking “de Blasio mode” button, which changed the estimated wait

time for a ride to 25 minutes and encouraged riders to “Say ‘NO’ to de Blasio’s

Uber.”

Tusk’s dalliance with New York’s literary scene

began during the early days of the pandemic in 2020, when he and Howard Wolfson

— a friend and another former Bloomberg consigliere — started the Gotham Book

Prize, which awards $50,000 annually to the author of a book about the city.

The first winner was the novel “Deacon King Kong” by James McBride in 2021,

followed by New York Times reporter Andrea Elliott’s nonfiction book “Invisible

Child: Poverty, Survival and Hope in an American City” this year.

Tusk characterized the store as a “microcosm” of one

of his favorite policy proposals: universal basic income, which he has

advocated at length, especially through Yang’s mayoral campaign. P&T Knitwear

offers higher wages than other bookstores do, he said, and provides workers

with the same extensive health benefits given to employees at his venture fund.

“I’ve had all this

luck,” Tusk said. “That’s sort of the back story behind the store.” He described

a chain of good fortune, stretching from his family surviving the Holocaust and

moving to America all the way to his decision to accept payment from Uber in

equity rather than cash. The store is just one facet of a broad program of

charitable works, he said, including pushing bills nationwide that mandate

school breakfast programs and funding a soup kitchen on 16th Street. “This is

just one person doing whatever feels right to me,” he said, “but this is how

I’m going about it.”

Read more Books

Jordan News