In the first days of Sudan’s war, the two university

students felt helpless.

They locked themselves in their apartment in the capital,

Khartoum, glued to Twitter as the battle unfolded. They winced as the walls

shuddered from blasts and gunfire, taking shelter in the corridor. They

wondered where Sudan was going.

اضافة اعلان

On the fifth day, April 19, the phone rang: Someone needed a

taxi.

A senior UN official, a woman in her 40s, was trapped inside

her home in an upscale neighborhood, the caller explained. Her situation was

desperate. Pickup trucks mounted with machine guns stood outside her building,

firing at warplanes that zoomed overhead. Black smoke was streaming into her

apartment after an airstrike nearby. She had run out of water. Her cellphone

battery was down to 5 percent. Could they rescue her?

The students, Hassan Tibwa and Sami Al-Gada, in their final

year of mechanical engineering, had a side gig driving a taxi. But this call

was not a paying job; it was a mercy run. Tibwa phoned the woman. “She was

screaming,” he recalled. “We had only a few minutes before her phone died. She

was on her own.”

They jumped into Gada’s car, a dinged, seven-year-old Toyota

sedan, and set off into the city, horrified at its transformation. Bullet holes

pocked buildings. Charred vehicles littered the streets. Fighters were

everywhere.

Crunching over bullet casings, they navigated a gantlet of

checkpoints manned by jittery fighters from the paramilitary Rapid Support

Forces (RSF), some wearing bandages or limping. The fighters scanned the

students’ phones and peppered them with questions. It took an hour to travel

6.4km.

“We went through hell,” Tibwa said.

They found the UN official, named Patience, alone at her

apartment in an apparently deserted building. She had been hiding in her

bathroom for days, slowly depleting three cellphones, she said, showing them a

scatter of bullet holes in her living room wall.

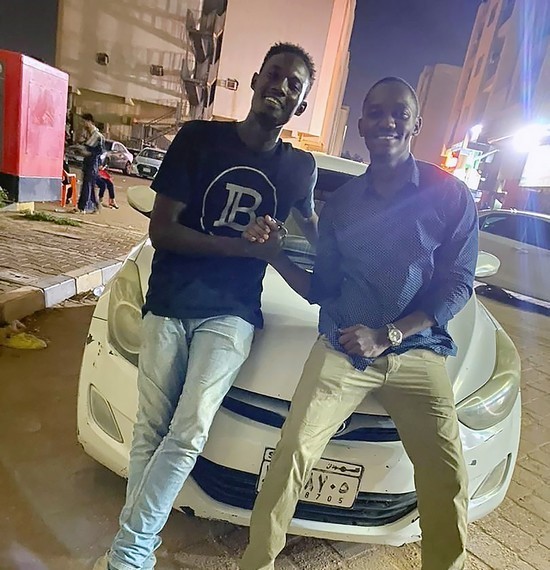

An undated photo via

Hassan Tibwa of himself, right, and Sami Al-Gada.

An undated photo via

Hassan Tibwa of himself, right, and Sami Al-Gada.

The students consoled her, wrapped her in an all-covering

abaya robe, and devised a cover story: Their passenger was pregnant and needed

to get to a hospital. They paused to say a prayer. “We knew that the moment we

stepped out, there was no going back,” Tibwa said.

Forty-five minutes and 10 checkpoints later, their Toyota

pulled up outside the Al-Salam, one of Khartoum’s most expensive hotels, now a

five-star refugee camp. Patience wept with relief. After collecting herself and

checking in, she sat the students down to ask an urgent question.

Could they go back and rescue her friends too?Over the next week, Tibwa, 25, and Gada, 23, rescued dozens

of desperate people from one of Khartoum's fiercest battle zones, according to

interviews with the students, those they extracted and hundreds of text

messages. Along the way, they were robbed, handcuffed, and threatened with

execution. Fighters accused them of being spies. Diplomats implored them to

retrieve their passports and pets. Shellfire and stray bullets fell around

their car.

“The bravery of these guys is just amazing,” said Fares

Hadi, an Algerian factory manager who survived a hair-raising ride with them

through Khartoum. “So impressive, so courageous.”

Every rescue interviewed said the students had not asked

for payment.

Over six days, as the war surged between two feuding

military factions — the army and the Rapid Support Forces group — the students

helped at least 60 people: South African teachers, Rwandan diplomats, Russian

aid workers and UN workers from many countries, including Kenya, Zimbabwe,

Sweden, and the US.

“The only word for them is heroes,” a UN official said.

From students to rescuersEven as Tibwa drove strangers to safety, his own family did

not know he was in Sudan.

He arrived in 2017 from Tanzania, where his family runs a

modest hardware store at a small town on Lake Victoria. An Islamic charity

provided a scholarship to study engineering at the International University of

Africa in Khartoum.

But he told his parents that he was going to study in

Algeria, in deference to their concerns about Sudan’s history of violent unrest

— a lie he easily maintained for six years, because he never had enough money

to go home.

Gada is Sudanese but was raised in a sleepy town in

northeastern Saudi Arabia, where his father was a car mechanic.

Classmates in university, the two young men soon became

friends. They shared a bright, open disposition and a gritty entrepreneurial

streak, working odd jobs at night to make rent. Tibwa drove a taxi that catered

mostly to African UN officials.

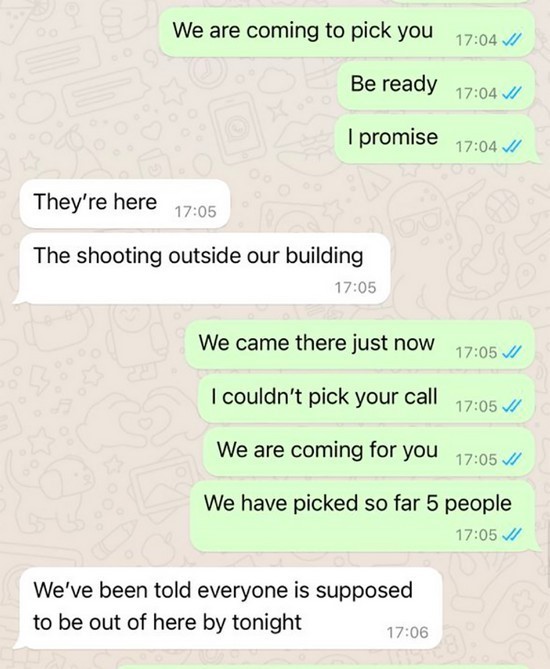

An undated image of a

series of texts between Hassan Tibwa and UN official who was trapped by

fighting in her apartment.

An undated image of a

series of texts between Hassan Tibwa and UN official who was trapped by

fighting in her apartment.

Sudan’s turbulent politics disrupted their ambition. Classes

were canceled for much of 2019 when roaring protesters, including Gada, helped

topple President Omar Al-Bashir, Sudan’s dictator of 30 years.

Then, in October 2021, Sudan’s two most powerful military

leaders — Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan of the army and Lt. Gen. Mohammed Hamdan

Dagalo of the RSF — joined forces to boot out the civilian prime minister and

seize power for themselves in a coup. Protests flared. The economy tanked.

The two students thought little, at first, of the shots that

rang out across Khartoum early on April 15: Anti-military demonstrators had

been clashing with riot police for more than a year.

But when Gada went to campus to submit a paper, the guards

sent him home. This time, it was not a protest, they said. It was war.

Tibwa and Gada were not the only rescuers. Local Resistance

Committees, formed years earlier to push Sudan toward democracy, pivoted to

helping Sudanese and foreigners flee.

But for some stricken residents, the two students were the

only option.

“They called us,” Tibwa said. “They didn’t have food. They

had no power. Their phones were going down. We tried to imagine ourselves in

that same situation. So we went out.”

A final rescueThe students’ final mission was their longest: a trip across

the Nile to the city of Omdurman, at the request of Rwandan diplomats, to

rescue a woman who, unlike the first they rescued, really was pregnant.

As their Toyota approached the house, the woman, who gave

her name as Fifi, texted them. She wrote, “Alhamdulilah” — Arabic for “Praise

be to God.” She was eight months pregnant and had been stranded with her young

son for 10 days.

By then, an exodus of foreigners from Khartoum was underway.

A dramatic helicopter evacuation the previous night of the

U.S. Embassy, led by the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 commandos, set off a cascade of

evacuations.

Most of the people the students had deposited at the Al

Salam finally left on a U.N. convoy of buses, cars, and four-wheel drives that

made a grueling 35-hour journey to Port Sudan. From there, many took ships

across the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia.

As the foreigners left, most of Khartoum’s 5 million

residents remained. The students stayed behind too, at first.

An undated photo of

Sami Al-Gada and Hassan Tibwa sharing a meal with soldiers of the Rapid Support

Forces, a paramilitary group.

An undated photo of

Sami Al-Gada and Hassan Tibwa sharing a meal with soldiers of the Rapid Support

Forces, a paramilitary group.

“Khartoum is getting empty now,” Tibwa said from their apartment

last week, the sound of gunfire rattling in the background.

But a day later, they were gone. A friendly RSF commander

had warned them that “something big was coming” in the city center, Tibwa said.

He advised them to get out while they could. They packed up the Toyota and

drove 22km to the edge of the capital, where Gada’s family has a house.

For a few days, they considered their options, working out,

drinking coffee, and reading novels. Fighter jets scudded over the horizon, and

a stray bomb landed nearby, killing members of a family in their home, they

said.

Tibwa wanted to stay in Sudan, a country he said he had

grown to love — and where he was a single semester away from completing his

engineering degree. But his time had run out.

On Wednesday, Gada dropped his friend on a street where he

hoped to catch a bus to Ethiopia and, from there, back to Tanzania.

A personal reckoning loomed, Tibwa noted ruefully: Now his

parents would learn that he had been studying in Sudan, not Algeria, all along.

As they separated, Tibwa pulled out his cellphone and began

filming.

“Saying goodbye to my boy, Sami,” he said as the Toyota

rolled down the street, his partner waving through the window. “See you, man.

See you.”

Read more Region and World

Jordan News