Did Western cultures affect indigenous Asian creative expression?

Layan Taifour, Jordan News

last updated: Sep 08,2022

“How could one even begin to make comparative judgments? Who would be able to say,

with any authority, that Plato is a greater political theorist than Mencius?

Who could compare The Canterbury Tales to The Tale of Genji? How do we evaluate

the art of Picasso against the creations of unknown African masters?” is a

question that Bruce D. Benson Centre for the Study of Western Civilization asks

when teaching Western Civilization in the University of Colorado.اضافة اعلان

According to Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, by Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler, the Westernization of Asian societies has been going on for centuries, with its claws digging deep into their hierarchies of art and literature.

The prolonged effects of Western cultures influencing the world’s art date back to the traders and colonizers from Western Europe, specifically ancient Greece, that settled on Asian (and African) land.

“When it is mentioned amongst Western elites, the traditions of the West are almost always an object of criticism or contempt,” Professor of Political Science at Swarthmore College James Kurth has said.

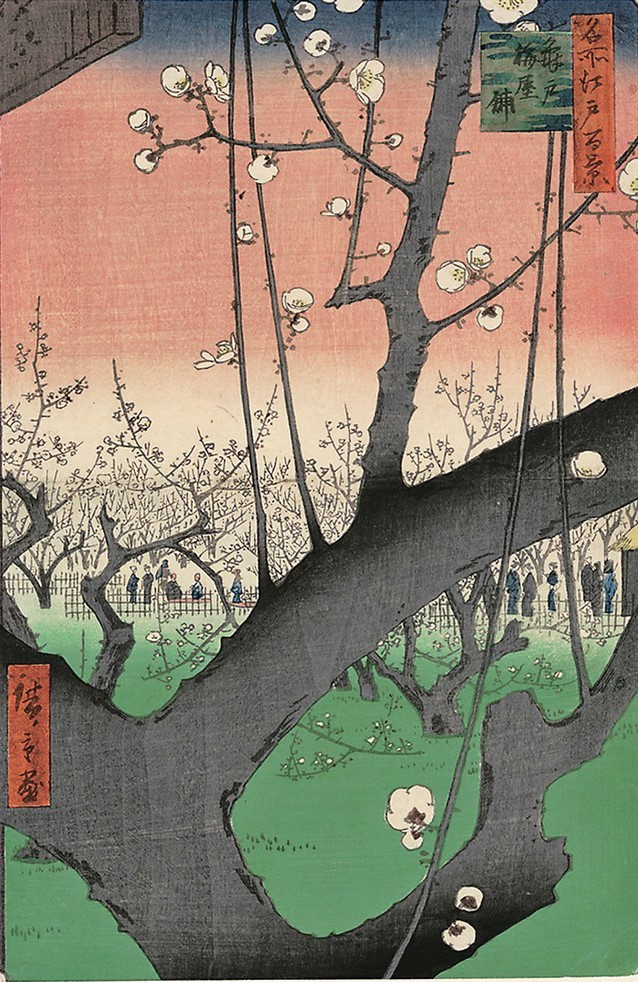

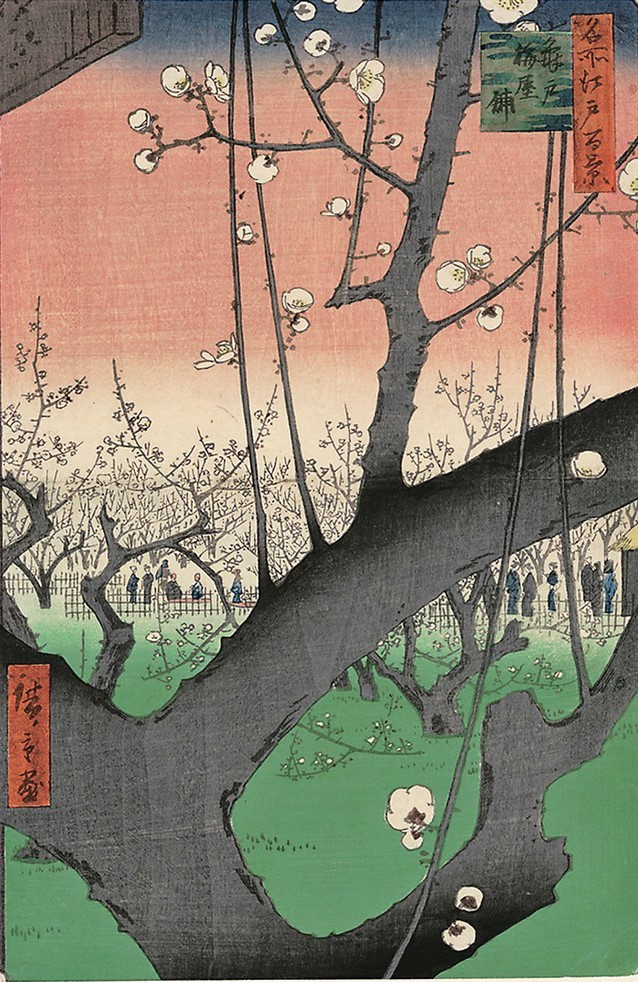

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Plum Estate. (Photo: Boston Museum Of Fine Arts)

These societies held the belief that their way of doing things, whether it is the written word or the stroke of a paint brush, was superior to the civilizations they were trying to colonize, Patricia Bauer, Professor of psychology at Emory University recently said. And to understand the deeply rooted effects of Western cultures on the artistic expression of many societies, one has to be aware of the long artistic and creative history of the world.

The evolution of art dates back to before 3000 BC, to the prehistoric times of humans. With simple cave paintings, the Neanderthals usually depicted themselves as stick figures, and also animals, starting the long history of artistic expression, according to Art in Context, an online art museum/archive.

The Middle Ages were a rough patch, often loosely regarded as the “artistic censorship era” by multiple scholars, with art typically consisting of manuscripts and mosaics, rather than the realism it used to focus on. During the Middle Ages, the teachings of the church overtook Europe and other parts of the world, their rules following behind, according to Brent F. Nelsen and James L. Guth, professors at Furman University, in their article Roman Catholicism and The Founding of Europe: How Catholics Shaped the European Communities.

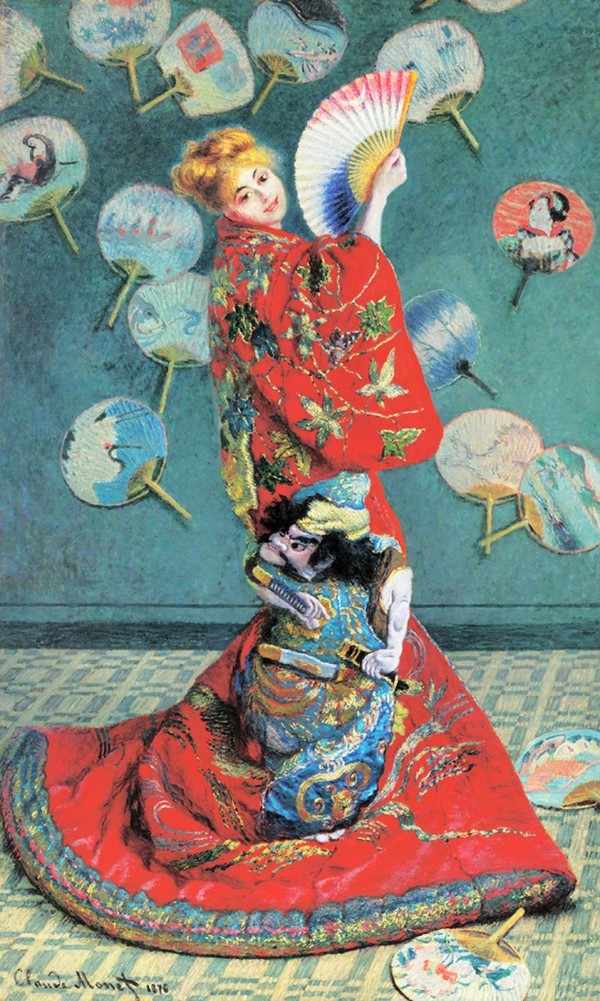

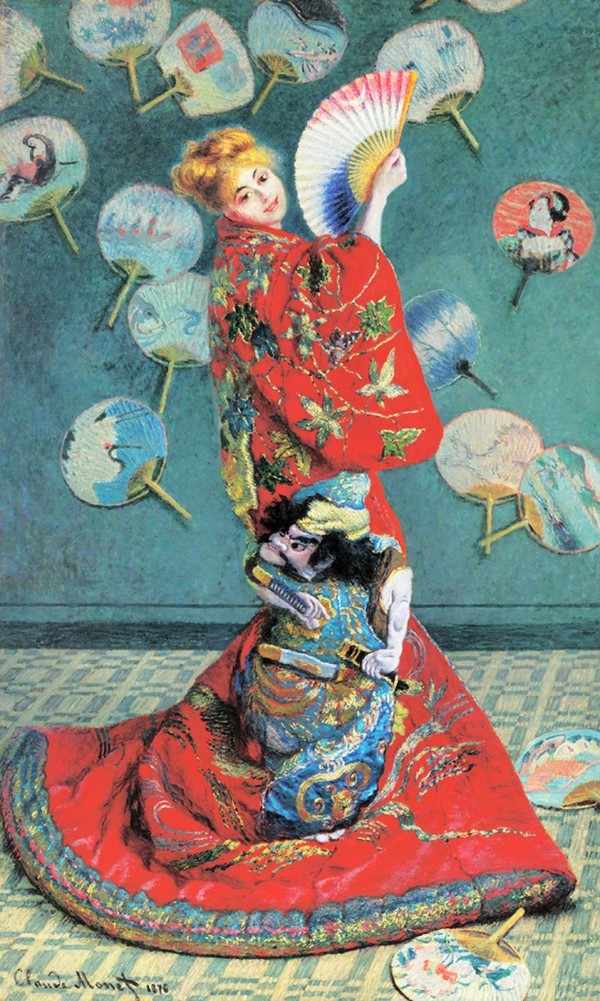

Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876. (Photo: Boston Museum Of Fine Arts)

Heavily focused on literature and religious studies, portrait paintings, and sculptures depicting the human form were incredibly rare. Dullness overtook art, with muted and age-ridden colours staining the once-vibrant artistic expressions of age-old artists. This specifically was apparent in Christianity reaching Japan, according to Tamon Miki, in the essay The Influence of Western Culture on Japanese Art, published by Sophia University.

A Christian Spanish missionary named Francis Xavier arrived on Japanese land accompanied by an artist named Anjiro. The missionary brought religious paintings adorned with Christian themes and used it to decorate his altars. These paintings were a means of instructing the public about Christianity, and hoping it would alter the minds of the public into following the teachings of the religion, in turn abiding by their stricter rules of art. It reached a point where a holy painting of the Virgin Mary was brought to Hirado, a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan, in 1565, and fell into the hands of Katō Kiyomasa, a Japanese daimyo (a general of a specific rank) of the Azuchi–Momoyama and Edo periods (according to Wikipedia), who was largely against Christianity infiltrating Japanese cultures, and made many efforts to ban it. This extended into the Renaissance, in the 1500s and 1600s, meaning it lasted for at least two centuries.

Yoshikazu — Yokohama-e print of an English Couple, 1861. (Photo: Visualizing Cultures)

Yet, in this era in Europe and many other countries, literature became abundant, mostly consisting of philosophy, religious treatises, legal texts, and a number of creative literary works. While medieval literature is a broad subject encompassing the many literary works produced during the Middle Ages, it is important to note its effect on the evolution of art and literature.

Literature became the gateway to freedom of expression when art could not fulfil that need due to censorship. It led to many notable discoveries that were popularised later, during the Renaissance. One of the interesting facts, however, is that the interest in Asian literature mostly arose after battling the storms of anthropological civilizationalism, ethno-history, and subalternism, according to Daud Ali, in his essay The idea of the Medieval in the Writing of South Asian History: Contexts, Methods and Politics”, published by Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

The Renaissance arrived with a blast, and the rebirth of art mingled with literature overtaking societies across the world. Turning from the mostly biblical scenes, Renaissance led art to include portraits yet again, alongside events from contemporary life. There was a revived boom of interest in classical learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome in Europe, with a growing political stability that allowed for freedom in literature and art.

The development of new technologies led to even bigger, prosperous contemporary and literary works, with the printing press becoming increasingly popular. However, with all of these developments came the discovery and exploration of new continents, as curiosity got the better of many European thinkers and philosophers. Their need for adventure called for a trip on the seas. It was there that the seed of Westernization was planted, blooming into something that later would be deemed as the problematic part of history.

“The Mi’raj of the Prophet” from the Khamsah of Shah Tahmasp. (Photo: Epoch Magazine)

One of the many ways that Western Cultures infiltrated Asia during the Renaissance was through the architecture.

“By the middle of the sixteenth century, Renaissance churches were being erected in Latin America and in Portuguese outposts in Asia. Colonial architecture continued to be a showcase for advanced European design ideas until well after World War II,” said Kathleen James-Chakraborty in her essay Resisting the Renaissance in the book Architecture since 1400, published by University of Minnesota Press.

The Catholic church back then decided to censor artists yet again, stifling creativity for a second time. They felt the need to not only control the doings of Europe and the neighbouring countries, but to also dig their claws into the creativity of Asian people. It gave way to a rise of Catholic missions, all of which had one goal: spread the religion as far and wide as possible, even if it meant colonizing the lands of indigenous people, and taking away their freedom of expression.

After the Renaissance came a time of wars in Europe, each country battling for a piece of territory in neighbouring countries. Realizing what was happening, they decided to expand their horizons, and overtake lands in Africa and Asia.

“By 1886 the rest of the region had been divided among the British, French, Dutch, and Spanish (who soon were replaced by the Americans), with the Portuguese still clinging to the island of Timor,” said William H. Frederick, an associate professor of history at Ohio University. This all led to the catastrophic infiltration of artistic expression of Asian cultures; it can be seen in many paintings, as mentioned by Tamon Miki: the altar paintings for a church in Yamaguchi (which were affected specifically by the Counter-Reformation and the wars of 1556), paintings that were presented to Ōmura Sumitada by Cosme de Torres, a Spanish priest trying to change Asian art into a reformed piece with Christian, Western influence.

Asian art has had a long history of Western influence due to the many different colonial empires and religious missions that set foot upon it, and it has survived even further influence with the current rise of globalisation and the insistent need to Westernize art by Europe and America.

Many artists have been trying to keep the history alive through their inspirations taken from old Asian pieces and literature. Trying to hold the heritage to its core values is hard, but it is important, since it holds many secret treasures in the world of art and literature.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News

According to Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, by Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler, the Westernization of Asian societies has been going on for centuries, with its claws digging deep into their hierarchies of art and literature.

The prolonged effects of Western cultures influencing the world’s art date back to the traders and colonizers from Western Europe, specifically ancient Greece, that settled on Asian (and African) land.

“When it is mentioned amongst Western elites, the traditions of the West are almost always an object of criticism or contempt,” Professor of Political Science at Swarthmore College James Kurth has said.

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Plum Estate. (Photo: Boston Museum Of Fine Arts)

These societies held the belief that their way of doing things, whether it is the written word or the stroke of a paint brush, was superior to the civilizations they were trying to colonize, Patricia Bauer, Professor of psychology at Emory University recently said. And to understand the deeply rooted effects of Western cultures on the artistic expression of many societies, one has to be aware of the long artistic and creative history of the world.

The evolution of art dates back to before 3000 BC, to the prehistoric times of humans. With simple cave paintings, the Neanderthals usually depicted themselves as stick figures, and also animals, starting the long history of artistic expression, according to Art in Context, an online art museum/archive.

The Middle Ages were a rough patch, often loosely regarded as the “artistic censorship era” by multiple scholars, with art typically consisting of manuscripts and mosaics, rather than the realism it used to focus on.Following 3000 BC, ancient Egypt and Greece, the Etruscans, and the Romans finally tried their hand at realistic depictions of human kind. Sculptures, busts, and human paintings were predominant for many centuries to come, especially in Ancient Greece. People back then, however, did not pride themselves on written works and literature. Their focus was on the seen and touched, rather than on the read and written, as Professor of Developmental Anatomy (1996) Gillian Morriss-Kay put it in her article The Evolution of Human Artistic Creativity.

The Middle Ages were a rough patch, often loosely regarded as the “artistic censorship era” by multiple scholars, with art typically consisting of manuscripts and mosaics, rather than the realism it used to focus on. During the Middle Ages, the teachings of the church overtook Europe and other parts of the world, their rules following behind, according to Brent F. Nelsen and James L. Guth, professors at Furman University, in their article Roman Catholicism and The Founding of Europe: How Catholics Shaped the European Communities.

Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876. (Photo: Boston Museum Of Fine Arts)

Heavily focused on literature and religious studies, portrait paintings, and sculptures depicting the human form were incredibly rare. Dullness overtook art, with muted and age-ridden colours staining the once-vibrant artistic expressions of age-old artists. This specifically was apparent in Christianity reaching Japan, according to Tamon Miki, in the essay The Influence of Western Culture on Japanese Art, published by Sophia University.

A Christian Spanish missionary named Francis Xavier arrived on Japanese land accompanied by an artist named Anjiro. The missionary brought religious paintings adorned with Christian themes and used it to decorate his altars. These paintings were a means of instructing the public about Christianity, and hoping it would alter the minds of the public into following the teachings of the religion, in turn abiding by their stricter rules of art. It reached a point where a holy painting of the Virgin Mary was brought to Hirado, a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan, in 1565, and fell into the hands of Katō Kiyomasa, a Japanese daimyo (a general of a specific rank) of the Azuchi–Momoyama and Edo periods (according to Wikipedia), who was largely against Christianity infiltrating Japanese cultures, and made many efforts to ban it. This extended into the Renaissance, in the 1500s and 1600s, meaning it lasted for at least two centuries.

Yoshikazu — Yokohama-e print of an English Couple, 1861. (Photo: Visualizing Cultures)

Yet, in this era in Europe and many other countries, literature became abundant, mostly consisting of philosophy, religious treatises, legal texts, and a number of creative literary works. While medieval literature is a broad subject encompassing the many literary works produced during the Middle Ages, it is important to note its effect on the evolution of art and literature.

Literature became the gateway to freedom of expression when art could not fulfil that need due to censorship. It led to many notable discoveries that were popularised later, during the Renaissance. One of the interesting facts, however, is that the interest in Asian literature mostly arose after battling the storms of anthropological civilizationalism, ethno-history, and subalternism, according to Daud Ali, in his essay The idea of the Medieval in the Writing of South Asian History: Contexts, Methods and Politics”, published by Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

The Renaissance arrived with a blast, and the rebirth of art mingled with literature overtaking societies across the world. Turning from the mostly biblical scenes, Renaissance led art to include portraits yet again, alongside events from contemporary life. There was a revived boom of interest in classical learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome in Europe, with a growing political stability that allowed for freedom in literature and art.

The development of new technologies led to even bigger, prosperous contemporary and literary works, with the printing press becoming increasingly popular. However, with all of these developments came the discovery and exploration of new continents, as curiosity got the better of many European thinkers and philosophers. Their need for adventure called for a trip on the seas. It was there that the seed of Westernization was planted, blooming into something that later would be deemed as the problematic part of history.

“The Mi’raj of the Prophet” from the Khamsah of Shah Tahmasp. (Photo: Epoch Magazine)

One of the many ways that Western Cultures infiltrated Asia during the Renaissance was through the architecture.

“By the middle of the sixteenth century, Renaissance churches were being erected in Latin America and in Portuguese outposts in Asia. Colonial architecture continued to be a showcase for advanced European design ideas until well after World War II,” said Kathleen James-Chakraborty in her essay Resisting the Renaissance in the book Architecture since 1400, published by University of Minnesota Press.

The development of new technologies led to even bigger, prosperous contemporary and literary works, with the printing press becoming increasingly popular.The Renaissance slowly dying led to the disastrous movement named the Counter-Reformation. It is less known that the Counter-Reformation is the movement that most heavily affected Asian countries and the overarching culture, as opposed to the Reformation of Martin Luther, according to Alexander Chow, a Chinese American instructor with a PhD in theology.

The Catholic church back then decided to censor artists yet again, stifling creativity for a second time. They felt the need to not only control the doings of Europe and the neighbouring countries, but to also dig their claws into the creativity of Asian people. It gave way to a rise of Catholic missions, all of which had one goal: spread the religion as far and wide as possible, even if it meant colonizing the lands of indigenous people, and taking away their freedom of expression.

After the Renaissance came a time of wars in Europe, each country battling for a piece of territory in neighbouring countries. Realizing what was happening, they decided to expand their horizons, and overtake lands in Africa and Asia.

“By 1886 the rest of the region had been divided among the British, French, Dutch, and Spanish (who soon were replaced by the Americans), with the Portuguese still clinging to the island of Timor,” said William H. Frederick, an associate professor of history at Ohio University. This all led to the catastrophic infiltration of artistic expression of Asian cultures; it can be seen in many paintings, as mentioned by Tamon Miki: the altar paintings for a church in Yamaguchi (which were affected specifically by the Counter-Reformation and the wars of 1556), paintings that were presented to Ōmura Sumitada by Cosme de Torres, a Spanish priest trying to change Asian art into a reformed piece with Christian, Western influence.

Asian art has had a long history of Western influence due to the many different colonial empires and religious missions that set foot upon it, and it has survived even further influence with the current rise of globalisation and the insistent need to Westernize art by Europe and America.

Many artists have been trying to keep the history alive through their inspirations taken from old Asian pieces and literature. Trying to hold the heritage to its core values is hard, but it is important, since it holds many secret treasures in the world of art and literature.

Read more Culture and Arts

Jordan News