Pierrot le Fou … artistic chronicle of an eternity announced

Israa Radaydeh, Jordan News

last updated: Oct 17,2022

For some films, the history

of cinema, popular culture, and the media have transformed them into cultural

objects, into myths, into symbols. Their poetic scope is intended to go beyond

the boundaries of a single viewing and is measured, above all, by what is said

about them — what they represent.اضافة اعلان

Such is the case with Pierrot le Fou (1965), a seminal work by filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. Fifty-five years after its release, we may now have enough hindsight to decipher what made the director’s tenth feature film such a phenomenon of pop culture and emblem of the French New Wave.

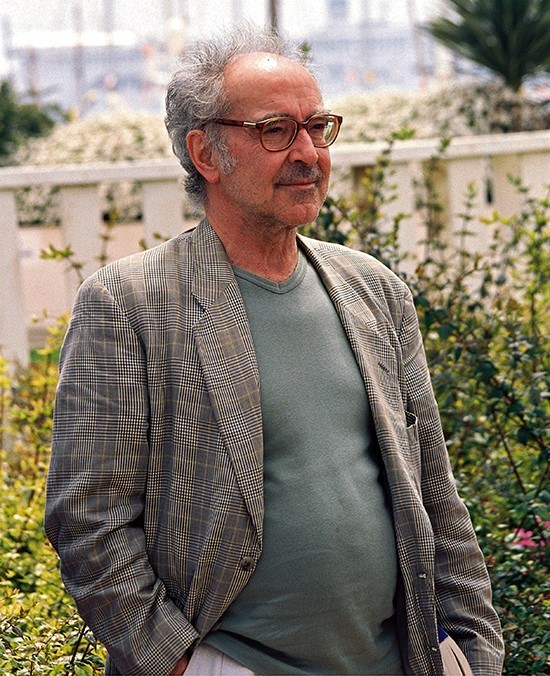

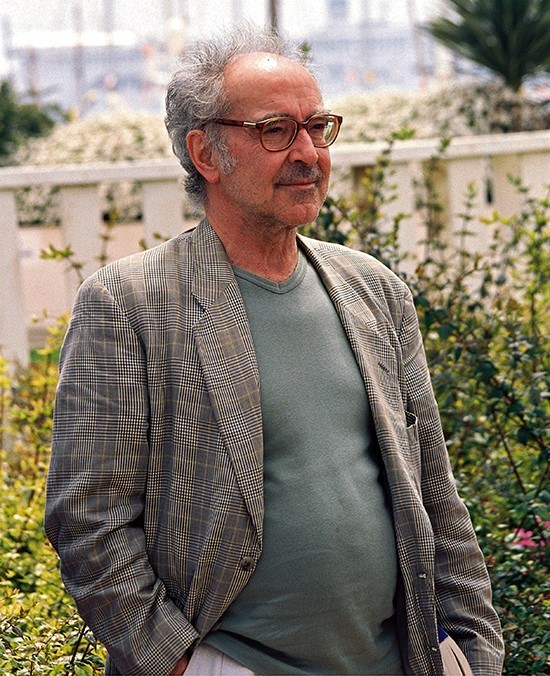

Jean-Luc Godard. (Photos: Shutterstock)

The classic film, a veritable mélange of arthouse movie, road movie, gangster movie, romantic comedy, and more, will be screened today at Rainbow Theater in Amman in honor of its iconic Franco-Swiss film director Godard. The event is being organized by The Royal Film Commission in collaboration with the Embassy of Switzerland, the Embassy of France, and the French Institute in Jordan.

An explosive affair

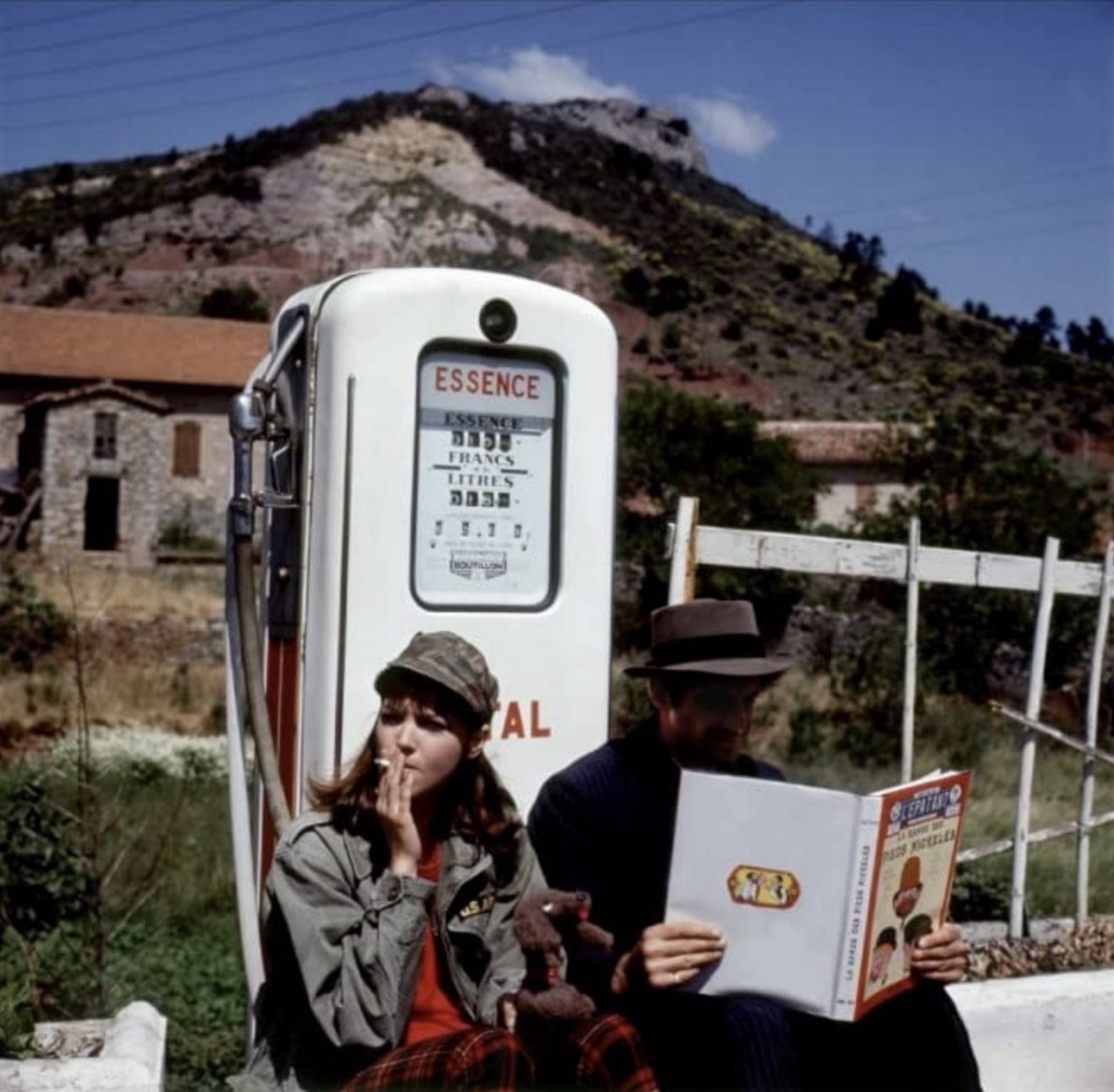

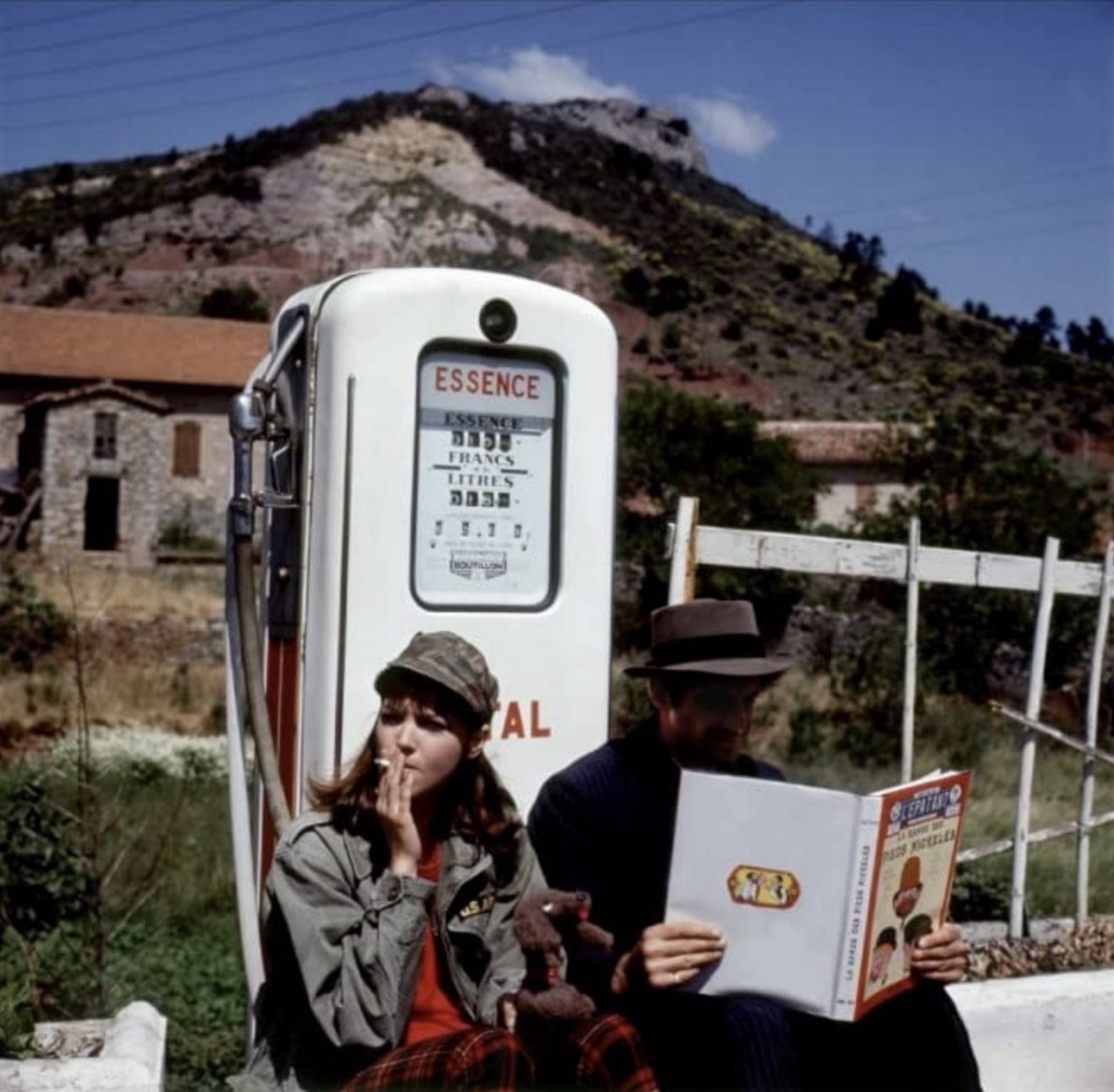

Pierrot le Fou is the hero of the film, but his name is not Pierrot, his name is Ferdinand Griffon. At least, that is what he constantly repeats to his children’s babysitter Marianne, who always calls him “Pierrot the crazy” to tease him. And indeed, the story of the unlikely couple, on the run in the south of France in search of love and freedom, does seem crazy, at least to them.

Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo), who starts out as a good Parisian bourgeois — educated, married, and the father of a family — leaves his decent social life behind to flee with his daughter’s young caretaker, Marianne (Anna Karina). The couple had become involved in an affair five years previous, but that experience had been short but sweet. Now, they have decided to rekindle their passion in a mad flight.

Over the course of their incredible adventures, we learn that Marianne is being chased by two criminals. The story is told in a fast-paced manner; the pair’s quest is literally explosive, dangerous, romantic, and poetic.

Riding the wave

Pierrot le Fou is a film that has stood the test of time. This comes out most strongly in the numerous quotes that have been incorporated into popular culture and the subsequent works of many other directors, (Quentin Tarantino and Xavier Dolan, for example) who, have taken on stylistic elements that flavor Godard’s works, sometimes in spite of themselves.

From the outset, the movie was a great critical and popular success. The year of its release, it exceeded one million theater admissions in France; a rare feat for a work with such experimental staging. The success of “le Fou” most certainly lies in its place within the current of the French New Wave.

Spearheading the wave, Godard is at the peak of his art in the film, which reinforces his aesthetic signature marked by a symbolic approach to colors, non-synchronization of images and sound, and theatrical staging.

Indeed, in Pierrot le Fou we notice the strong symbolic presence of blues and reds, faithful to the “Godardian style”, along with a pop approach to lighting. At times, the filmmaker uses color filters; at times, he applies strongly colored and assumed lighting to night scenes. In short, Godard creates a universe similar to that of the comic strip, straying from realism.

An icon

“JLG” was one of the most iconoclastic filmmakers of his art: sunglassed with a cigar in his mouth, he left a mark on generations of film fans with cult films such as Contempt.

“I only want to talk about cinema. Why talk about anything else? With cinema, we talk about everything, we get to everything,” he famously said, in a drawling accent.

The director shot around fifty feature films starting in the 1960s, to which are added dozens of short films. One of the most studied filmmakers in the world; he was honored with a César and an Oscar for his career, as well as a special Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2018. The films of the man with tortoiseshell glasses stood out for their unique, nervous editing, a very personal use of literary quotations, or their provocative spirit.

JLG has always divided critics and the public: for some, he is a genius; for others, a filmmaker with hermetic work. He had a way of grabbing attention and occupying the field of film theory like no other, delivering his precepts: “When you go to the cinema, you raise your head. When you watch television, you lower it.”

When Godard decided to make Pierrot le Fou, the filmmaker was far from suspecting that he was creating the future icon of a generation.

Making fun of Hollywood

To speak of art in the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard would obviously require more than one article. An encyclopedia would not suffice to discuss the subject. One theme could be broached by evoking his later films, in particular, Goodbye to Language (2014) and The Image Book (2018). Both are sensory and reflexive cinematographic experiences, intertwining the poetic and the political. This omnipresence of art within the seventh art itself is a constant in the filmmaker’s career, with hints first emerging in Pierrot le Fou (1965).

The film is, in fact, at the junction of three trends.

First, there is the resurgence of the caustic Godard, who pays homage to and simultaneously makes fun of classic Hollywood cinema, as seen in Breathless (1960). The story of the couple formed by Marianne and Ferdinand has notes of the detective film within a frenzied road movie punctuated with philosophical variations on impossible love. If it mixes and subverts these different cinematographic genres, the work also anticipates the more openly militant turn taken by Godard at the end of the 60s.

Political tones in La Chinoise, which was released on screens in 1967, were already announced in Pierrot le Fou, which denounces both consumer society and American foreign policy. The screen zooms in on advertisements, one for a brand of women’s underwear that elicits an ironic comment from the hero, in English voice-over: “There was the Athenian civilization, there was the Renaissance, and now we are entering the civilization of ass.”

Art is both inside and outside the narrative. From the outset, it is conceived as a critical cinematographic tool, superimposed on the narration whenever it is not simply included. With this, Godard enriches the film and the story it tells, bringing additional meaning to the staging. We go, for example, from a close-up of Marianne to a painting by Renoir, renamed “Marianne Renoir” on the occasion. Certain scenes are downright interspersed with shots having nothing to do with what precedes. Take, for example, the action scene interrupted by “Las Vegas” neon lights, filmed close-up to the sound of classical music.

These contrasts can sometimes take a much more explicit path. How not to follow this ulterior plan when we see paintings by Picasso enthroned next to Kalashnikovs? Superimposing two such conceptually distant objects into the same frame seems like a cynical mockery that lowers art to a highly dubious capital market.

‘Made of dreams’

Art is not only a material element affixing itself to the narration, it also creeps into the dynamics between the heroes. We see it when Marianne confides to Ferdinand that she would like “life and the novel to be the same: clear, logical, organized”.

Pierrot le Fou is a work that is lived in chaos, which permanently strides a vast cinematographic gap, ranging from burlesque to detective, and from romance to musical comedy. In one and the same scene, one passes from laughter to tears. The bubbling energy that the film harbors retains the DNA of the “New Wave” at the same time as it foresees the political agitations of May 1968. By staging ban-breaking protagonists, Godard subverts “dad’s cinema” and the bourgeois society to which he is attached.

The story that Ferdinand and Marianne live, full of sound and fury, is also that of characters who choose to live as if on screen. By deciding to escape their daily lives, they acquire a new freedom. They soon become the heroes of their own “adventure film”, as they themselves state in the voiceover. With them, every act or event is likely to transform in unexpected ways. They make their cinema within the cinema itself.

This mise en abyme is not the only one at the center of the film. Pierrot le Fou is, in fact, structured around a reflection on the value of art and, more specifically, that of cinema. The work is based on the postulate of the eponymous hero, who affirms: “We are made of dreams and the dreams are made of us.”

The phrase should not be taken as a celebration of psychoanalysis. For the director, dreams are entirely artistic — one could even say exclusively cinematographic — since they are realized, in the film, only through the bias of the seventh art. Ferdinand is an informal self-portrait of the filmmaker, who reaffirms through his character the limitless imaginative power of cinema. If art can influence life (and vice versa), it can also create interference with it, going so far as to blur the bounds between life and artistic fiction. Ferdinand gradually becomes Pierrot le Fou the fictional character, the hero that he himself built with Marianne, even if it leads to his death.

Death on a blue background

This fiction that the characters play out, within what is already a cinematographic fiction, has a morbid tone from the outset. Pierrot le Fou constructs a meta picture-within-picture, where art puts itself to death.

This inevitability is omnipresent, and constantly recalled by various artistic means deployed by characters and director alike. Art thus has a double function: to both announce the future of the heroes, and to delay it.

Think of this moment at the beginning of the film, where the narration is cut by a close-up of comics, imprinted with writing: “Rendezvous with death”. When Ferdinand is assaulted by mysterious strangers, the director moves the encounter off-screen, replacing it with a painting by Picasso. The distancing of the event does not attenuate the violence it presupposes.

Godard directs a story that narrates the birth and death of a couple. If art allows Marianne and Ferdinand’s reunion at the beginning, it very quickly becomes a vector of incomprehension between them. Unlike Ferdinand, Marianne is a young woman who sees existence with as much lightness and inconsistency as the heroes of novels.

The final scene of the movie constitutes the poetic and political culmination of the plot. Godard manages to condense into a single scene all the obsessions of a film which permanently asserts itself as the cinematographic chronicle of an (artistic) eternity announced.

Read more Reviews

Jordan News

Such is the case with Pierrot le Fou (1965), a seminal work by filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. Fifty-five years after its release, we may now have enough hindsight to decipher what made the director’s tenth feature film such a phenomenon of pop culture and emblem of the French New Wave.

Jean-Luc Godard. (Photos: Shutterstock)

The classic film, a veritable mélange of arthouse movie, road movie, gangster movie, romantic comedy, and more, will be screened today at Rainbow Theater in Amman in honor of its iconic Franco-Swiss film director Godard. The event is being organized by The Royal Film Commission in collaboration with the Embassy of Switzerland, the Embassy of France, and the French Institute in Jordan.

An explosive affair

Pierrot le Fou is the hero of the film, but his name is not Pierrot, his name is Ferdinand Griffon. At least, that is what he constantly repeats to his children’s babysitter Marianne, who always calls him “Pierrot the crazy” to tease him. And indeed, the story of the unlikely couple, on the run in the south of France in search of love and freedom, does seem crazy, at least to them.

Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo), who starts out as a good Parisian bourgeois — educated, married, and the father of a family — leaves his decent social life behind to flee with his daughter’s young caretaker, Marianne (Anna Karina). The couple had become involved in an affair five years previous, but that experience had been short but sweet. Now, they have decided to rekindle their passion in a mad flight.

Over the course of their incredible adventures, we learn that Marianne is being chased by two criminals. The story is told in a fast-paced manner; the pair’s quest is literally explosive, dangerous, romantic, and poetic.

Riding the wave

Pierrot le Fou is a film that has stood the test of time. This comes out most strongly in the numerous quotes that have been incorporated into popular culture and the subsequent works of many other directors, (Quentin Tarantino and Xavier Dolan, for example) who, have taken on stylistic elements that flavor Godard’s works, sometimes in spite of themselves.

From the outset, the movie was a great critical and popular success. The year of its release, it exceeded one million theater admissions in France; a rare feat for a work with such experimental staging. The success of “le Fou” most certainly lies in its place within the current of the French New Wave.

Spearheading the wave, Godard is at the peak of his art in the film, which reinforces his aesthetic signature marked by a symbolic approach to colors, non-synchronization of images and sound, and theatrical staging.

Indeed, in Pierrot le Fou we notice the strong symbolic presence of blues and reds, faithful to the “Godardian style”, along with a pop approach to lighting. At times, the filmmaker uses color filters; at times, he applies strongly colored and assumed lighting to night scenes. In short, Godard creates a universe similar to that of the comic strip, straying from realism.

An icon

“JLG” was one of the most iconoclastic filmmakers of his art: sunglassed with a cigar in his mouth, he left a mark on generations of film fans with cult films such as Contempt.

“I only want to talk about cinema. Why talk about anything else? With cinema, we talk about everything, we get to everything,” he famously said, in a drawling accent.

The director shot around fifty feature films starting in the 1960s, to which are added dozens of short films. One of the most studied filmmakers in the world; he was honored with a César and an Oscar for his career, as well as a special Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2018. The films of the man with tortoiseshell glasses stood out for their unique, nervous editing, a very personal use of literary quotations, or their provocative spirit.

JLG has always divided critics and the public: for some, he is a genius; for others, a filmmaker with hermetic work. He had a way of grabbing attention and occupying the field of film theory like no other, delivering his precepts: “When you go to the cinema, you raise your head. When you watch television, you lower it.”

When Godard decided to make Pierrot le Fou, the filmmaker was far from suspecting that he was creating the future icon of a generation.

Making fun of Hollywood

To speak of art in the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard would obviously require more than one article. An encyclopedia would not suffice to discuss the subject. One theme could be broached by evoking his later films, in particular, Goodbye to Language (2014) and The Image Book (2018). Both are sensory and reflexive cinematographic experiences, intertwining the poetic and the political. This omnipresence of art within the seventh art itself is a constant in the filmmaker’s career, with hints first emerging in Pierrot le Fou (1965).

The film is, in fact, at the junction of three trends.

First, there is the resurgence of the caustic Godard, who pays homage to and simultaneously makes fun of classic Hollywood cinema, as seen in Breathless (1960). The story of the couple formed by Marianne and Ferdinand has notes of the detective film within a frenzied road movie punctuated with philosophical variations on impossible love. If it mixes and subverts these different cinematographic genres, the work also anticipates the more openly militant turn taken by Godard at the end of the 60s.

Political tones in La Chinoise, which was released on screens in 1967, were already announced in Pierrot le Fou, which denounces both consumer society and American foreign policy. The screen zooms in on advertisements, one for a brand of women’s underwear that elicits an ironic comment from the hero, in English voice-over: “There was the Athenian civilization, there was the Renaissance, and now we are entering the civilization of ass.”

Art is both inside and outside the narrative. From the outset, it is conceived as a critical cinematographic tool, superimposed on the narration whenever it is not simply included. With this, Godard enriches the film and the story it tells, bringing additional meaning to the staging. We go, for example, from a close-up of Marianne to a painting by Renoir, renamed “Marianne Renoir” on the occasion. Certain scenes are downright interspersed with shots having nothing to do with what precedes. Take, for example, the action scene interrupted by “Las Vegas” neon lights, filmed close-up to the sound of classical music.

These contrasts can sometimes take a much more explicit path. How not to follow this ulterior plan when we see paintings by Picasso enthroned next to Kalashnikovs? Superimposing two such conceptually distant objects into the same frame seems like a cynical mockery that lowers art to a highly dubious capital market.

‘Made of dreams’

Art is not only a material element affixing itself to the narration, it also creeps into the dynamics between the heroes. We see it when Marianne confides to Ferdinand that she would like “life and the novel to be the same: clear, logical, organized”.

Pierrot le Fou is a work that is lived in chaos, which permanently strides a vast cinematographic gap, ranging from burlesque to detective, and from romance to musical comedy. In one and the same scene, one passes from laughter to tears. The bubbling energy that the film harbors retains the DNA of the “New Wave” at the same time as it foresees the political agitations of May 1968. By staging ban-breaking protagonists, Godard subverts “dad’s cinema” and the bourgeois society to which he is attached.

The story that Ferdinand and Marianne live, full of sound and fury, is also that of characters who choose to live as if on screen. By deciding to escape their daily lives, they acquire a new freedom. They soon become the heroes of their own “adventure film”, as they themselves state in the voiceover. With them, every act or event is likely to transform in unexpected ways. They make their cinema within the cinema itself.

This mise en abyme is not the only one at the center of the film. Pierrot le Fou is, in fact, structured around a reflection on the value of art and, more specifically, that of cinema. The work is based on the postulate of the eponymous hero, who affirms: “We are made of dreams and the dreams are made of us.”

The phrase should not be taken as a celebration of psychoanalysis. For the director, dreams are entirely artistic — one could even say exclusively cinematographic — since they are realized, in the film, only through the bias of the seventh art. Ferdinand is an informal self-portrait of the filmmaker, who reaffirms through his character the limitless imaginative power of cinema. If art can influence life (and vice versa), it can also create interference with it, going so far as to blur the bounds between life and artistic fiction. Ferdinand gradually becomes Pierrot le Fou the fictional character, the hero that he himself built with Marianne, even if it leads to his death.

Death on a blue background

This fiction that the characters play out, within what is already a cinematographic fiction, has a morbid tone from the outset. Pierrot le Fou constructs a meta picture-within-picture, where art puts itself to death.

This inevitability is omnipresent, and constantly recalled by various artistic means deployed by characters and director alike. Art thus has a double function: to both announce the future of the heroes, and to delay it.

Think of this moment at the beginning of the film, where the narration is cut by a close-up of comics, imprinted with writing: “Rendezvous with death”. When Ferdinand is assaulted by mysterious strangers, the director moves the encounter off-screen, replacing it with a painting by Picasso. The distancing of the event does not attenuate the violence it presupposes.

Godard directs a story that narrates the birth and death of a couple. If art allows Marianne and Ferdinand’s reunion at the beginning, it very quickly becomes a vector of incomprehension between them. Unlike Ferdinand, Marianne is a young woman who sees existence with as much lightness and inconsistency as the heroes of novels.

The final scene of the movie constitutes the poetic and political culmination of the plot. Godard manages to condense into a single scene all the obsessions of a film which permanently asserts itself as the cinematographic chronicle of an (artistic) eternity announced.

Read more Reviews

Jordan News